It’s Pride Week at Lewton Bus! All week long we’re celebrating works that portray the trials and triumphs of queer lives.

“The one we barely see is Daniel, the sissy’s coming out of the closet more every day”

“Is that why you don’t want to see him?”

“No, it’s not that. He says he wants to be in other surroundings.

”

Intimacy.

Y Tu Mamá También by Alfonso Cuarón opens by presenting the relationship that the male leads, Julio and Tenoch, have with their girlfriends. Their soon-to-be-expanded ideas of sexuality are sophomoric and self-centered. Their interest in the opposite sex is a curiosity of conquest; they see hills to be cleared and roads to be mapped.

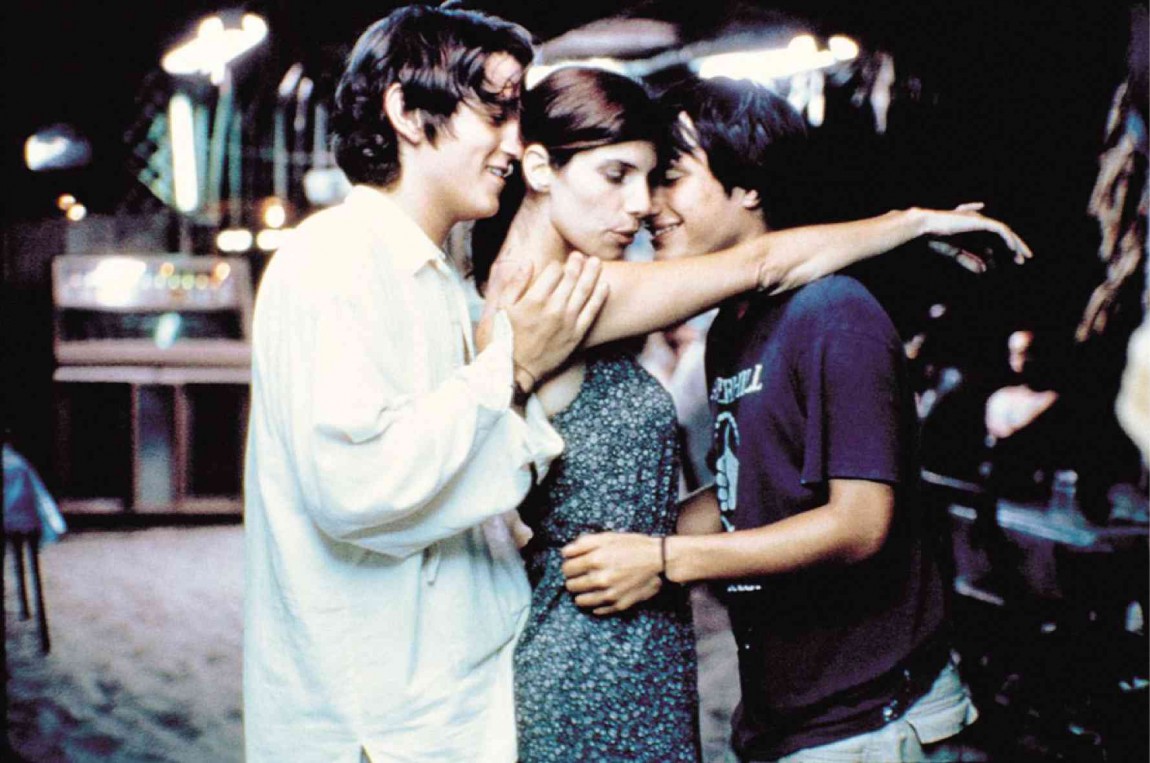

To their benefit, though they can’t yet see it, this enables them to share an intimacy with each other that is far more earnest than they have with their girlfriends, families, or even other friends. In the first act of the film, we see that these two have a shameless rapport, able to comment on each other genitals, experiences, and farts. They have true affection for each other, following parallel paths that gradually curve together.

They have a word for each other, as lovers do, even if they arrive at it accidentally: The Charolastra Club. This secret society includes Julio and Tenoch, their stoner friend Saba, lone girl La Pecas (who, because of her nefarious boyfriends, they only accept in an “honorary” capacity), and the unseen Daniel, who came out as gay and has since been distanced from the group. They justify his absence, claiming that he wants to be in different environments, oblivious to the possibility that their wanton use of a homophobic slur drove him away despite their supposed acceptance of him.

online pharmacy purchase strattera online best drugstore for you

Experience.

Teenagers live in a world in which posturing is often indistinguishable from frankness. In their first interactions with Luisa (played with commitment by Maribel Verdú), they corner her, literally, with projections of coolness and availability. Luisa sees through them in a way that is imperceptible to them. The movie makes sure you understand that Luisa hasn’t lived her best life, that her experience has been marred by circumstance. She had an overbearing conservative aunt; gave up her ambitions in favor of a job; knew love with a dead boyfriend about whom she talks as if he was fantastical; endured a marriage based on gratitude and lies. She doesn’t need to have seen the whole of the world to understand its depth, and certainly not to understand men. When she’s around them she conducts herself as if on a plane outside their reach, with little effort.

Luisa only ever wanted to travel. Mexico is an interesting place through which to view the world. There’s a great density of experience in this land in which stories of struggle have been beaten into platitudes. The film’s voiceover narration, delivered by Daniel Giménez Cacho, describes these stories with a matter-of-fact cadence that, for outsiders, may not do justice to the surreality of it all. In their teens, Tenoch and Julio are just beginning to comprehend the nature of their situation, while Luisa is ready and willing to take in everything she sees.

Conquest.

Tenoch, the aspiring writer, was almost named Hernan, the name of the conquistador who took Tenochtitlan for the Spanish crown. The movie tells us his father was overcome with a sense of nationalism. Luisa, however, is named Cortez, and like that conquistador of old, her mere presence wreaks havoc among the native population. The boys, just like the Mexica before them, never had a chance. Maybe they never really believed that Luisa would accept their far-fetched invitation to a fantastical Mexican beach; they aren’t the kind of guys to think things through.

As we gather up all of the ingredients for a road trip movie, Luisa responds to her very shitty day by making the most important call of her life to two idiot boys.

Luisa effortlessly cuts through them. Next to her, they are the barest imitations of people. Their skin may as well be translucent, their thoughts spoken out loud. The childishness of their play is earnest and endearing, and as always in her life Luisa makes do; she is at times a friend, a lover, a teacher, and a mother. The decisions she makes, filtered through the bleakness of death’s certainty, are an act of conquest, not over the boys, but over life itself. In her last adventure she allows herself to be all the things she is and all the things she never will be.

Betrayal.

Luisa fucks each of them, scaling the shallowest cliffs by demonstrating to them just how sexually inexperienced they actually are. In a jealous rage they confess to sleeping with each other’s girlfriends accuse each other of betrayal. Their girlfriends are perfunctory, objects via through which they define their relationship; they are therefore angry not because they’ve hurt their girlfriends, but because they have damaged their own trust in each other.

online pharmacy purchase ivermectin online best drugstore for you

She points the obvious out to them: they have unwittingly built their lives on their fixations and attractions to each other. Their brains barely process this.

Reckoning.

Their numbers dwindling, rural Mexican beaches are miracles, all of them. When the group arrives at paradise, the tension slowly breaks. Luisa, bare-breasted in the distance, claims the beach. They meet a Mexican family who lives off the sea and who helps bring them together again with kindness and tequila. The boys kiss and fuck. This was the most talked about scene in Mexico back when the movie came out. Mexican society is very richly textured, but its conservative roots were still very much in play and the only logical, emotionally honest conclusion to the story was popularly reduced to a stunt. Gael Garcia Bernal would go on to make the priest-boning movie El Crimen Del Padre to cement his place as a man whose characters put their genitals where they shouldn’t. For a couple seconds though, Tenoch and Julio shed their pretensions to share a moment of honest beauty.

On the way home, after not talking most of the way, Tenoch and Julio reckon with the experience that will shape their perspective on the spectrum of sexuality with a few lines about their unseen friend Daniel.

“Daniel?”

“He’s flaming. His father threw him out of the house”

“Fuck, that sucks”

“Well, he’s super happy the fucker, has a boyfriend and everything”

“That’s cool”