Our society is built by institutions. We feel the need to trust them to maintain peace. At the end of the day, said institutions are created and run by people with flaws and interests of their own, making them vulnerable to their corruption. Tom Tywker took that frustration and made it the thematic backbone of his spy thriller The International.

The movie follows Interpol agent Louis Salinger (played by Clive Owen), who is investigating the International Bank of Business and Credit for a weapons deal that would help it profit from the debt generated in wars all over the world. Tywker elevated that apparently straightforward premise by elegantly understating its genre elements and prioritizing raw tension over blockbuster spectacle.

The International opens with Salinger standing on the streets of Berlin, waiting for an informant to provide valuable intelligence that could bring down the IBBC. His partner in the task dies shortly afterwards for no immediately discernible reason. Just like that, we know exactly the type of world this story takes place in. One where crowds and public spaces aren’t enough to protect you from the most insidious threats. A war is taking place right in front of our eyes and no one is noticing it, because its soldiers are framing their battles as accidents or isolated crimes.

Throughout the course of his investigation, Salinger is encouraged to abandon it and leave it to someone else. Not only that, the people he has to deal with use his troubled past to gaslight him and make his colleagues doubtful of his methods and motives. Tywker codes this situation so the audience quickly identifies the larger problem he’s referring to; The way authorities treat Salinger is reminiscent of how political organs manipulate their constituents to keep them satisfied with the status quo and imply grave consequences if it’s challenged. Salinger is acting within the boundaries of law, and the IBBC weaponizes those boundaries to generate a sense of distrust around the people in charge of bringing accountability to those in power.

Clive Owen brings Salinger to life with a career standout performance that’s closer in tone to a self-contained character study than it is to a globetrotting thriller about fraudulent businessmen and missiles. Owen acts like a man who has seen enough dread to adopt rage and impatience as his standard emotional mode, but also enough decency to keep the hope of delivering justice in a cold-blooded world that prioritizes functionality over ethics. There’s no power fantasy element nor fist-pumping panache, just an honest portrayal of the toll distrust in society and paranoia take on our lives.

The plot is driven, in good part, by procedural sleuthing. To avoid overwhelming the viewers with exposition, Tywker provides clear and carefully detailed imagery to paint a picture of the crimes at hand. Every shot is easy to digest and given enough time to be properly processed before moving on to the next plot point. In a genre that can often be overwhelmingly fast paced in the way it delivers information, this approach feels almost therapeutic. Special mention goes to the score (composed by Tywker himself, Reinhold Heil and Johnny Klimek), which adds a chilling and sophisticated atmosphere to the proceedings.

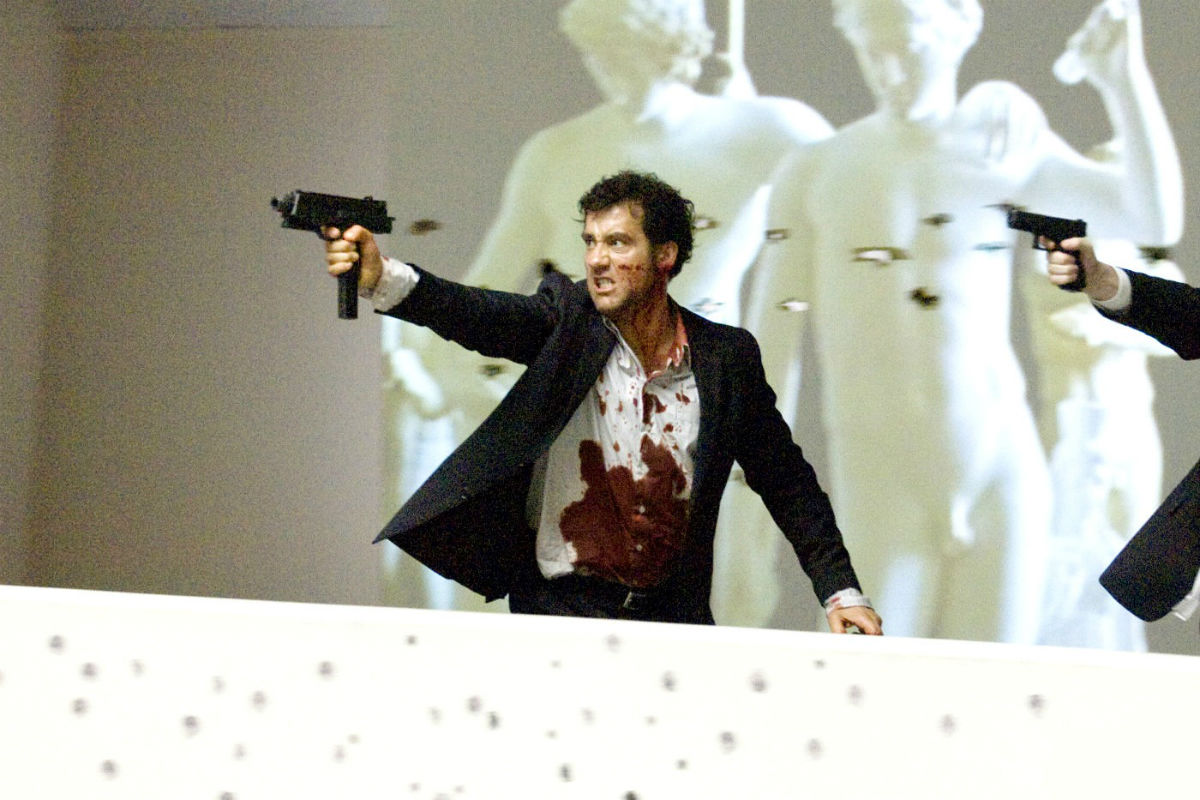

The International isn’t really an action movie. However, it does have a breathtaking action scene that’s worth a dissection. The shootout at the Guggenheim Museum in New York City is, in a way, the heart of the film. Not only for being the most impressive in terms of technical prowess, but for encapsulating the film’s themes and character work. Tywker took advantage of the Guggenheim’s idiosyncratic architecture to play with the way the camera moves and how the characters plan their attacks. The sudden burst of violence in such a high-profile location sheds light on the desperation Salinger and the IBBC have been experiencing with their respective hunts. The tension was just too high to be contained. The fact that we can see the suffering of innocent bystanders doesn’t allow us to lose ourselves in the excitement of the fight. With the civilians’ perspective, we can be aware of the horror one would feel if trapped in a situation like this. Throughout the set piece, it’s clear that Salinger is experienced in gunplay and tactical engagement. Yet that doesn’t stop him from being afraid of possibly losing his life in combat, especially because he wasn’t prepared for it. Owen sells Salinger’s anxiety by acting in a somewhat clumsy fashion when he’s hurt or cornered, but with an air of swiftness to convey Salinger’s never-ending determination to destroy the IBBC.

Eventually, the IBBC’s constant tampering of Salinger’s work lead him to question if his job was actually leading to a meaningful endgame. He comes to the realization that the system he serves thinks of him as a pawn and not as an agent of change and justice. Just like citizens need banks and governments to properly function as a society, the people in charge of said banks and governments desired an organization that could take care of their immoral agendas with enough discretion to maintain credibility. It’s a bleak thesis, and the movie doesn’t have a specific answer to the problem. However, it does take a look at the ways in which people can react to the status quo’s prioritization of power over public service, and the boundaries that get crossed in the process.

Salinger recognizes that the IBBC has expanded to a point where taking it down with legal procedures is virtually impossible. The truth of the situation is that no one in power wants to get rid of organizations of this nature because they’re convenient, silent and efficient. The only way Salinger can bring the IBBC to its knees is by acting like the IBBC itself, i.e., as a phantom that answers to no one. The indifference from his superiors lead Salinger to break his own rules, and he hates it. But he hates the idea of working in service of a rotten worldview even more.

When Salinger confronts Jonas Skarsen (the leading IBBC chairman) in Istanbul, he’s so enraged that he seriously considers the possibility of killing Skarsen in cold blood to compensate for the lack of results he has received from the authorities he serves. But when Skarsen is taken down by an assassin, Salinger is left right in the border between the man he used to be and the man he was forced to become. He didn’t fully cross the line into vigilantism, so there’s the possibility of him renewing the life he used to have an Interpol, even though he’s now skeptical of its reliability. Salinger’s path forward is left ambiguous. Just like fate of the IBBC, which suffered a heavy blow from its transgressions, but is still functional and an important part of the movie’s financial landscape. The key idea is that these institutions can only be corrected or wiped out if there’s enough will from other power structures and society at large. However, individual actions shouldn’t be understated in the process, since they can set important precedents.

The International’s particular brand of cynicism not only serves as a cathartic outlet for the fear towards banks and their abuse of the trust society places in them. It encourages the viewer to stay aware of how the elite twist information to frame reality to their liking, and how they exhaust us emotionally so we stop working for trustworthy institutions and settle for structures that benefit from collective suffering and loss.