Interactive storytelling is the true greatness and potential of games as a medium. In no other artform can the audience actively participate in the story and have it become their own. In interactive narratives the journey and arc that truly matters is that of the player as they experience the story, and the variance of this between different players is what allows the same story to mean different, personal things to different people to an extent no other medium can accomplish. All good games utilise this to their advantage, from Spec-Ops: The Line’s slow descent into hell to Metal Gear Solid 2’s deconstruction of videogame sequels and player expectations of them. Which makes games’ close association with film, an entirely non-interactive medium, so interesting.

Videogames and movies have been closely intertwined since the former’s early days, and their relationship really proliferated with the rise of consoles and tie-in games, with Raiders of the Lost Ark and ET becoming some of the Atari 2600’s most popular titles (and the latter killing the American gaming industry). As graphics became more advanced games began not only being based on films but drawing heavy influence from them in terms of storytelling techniques. This usually took the form of either lifting story elements wholesale or directly copying film’s visual language, the latter of which peaked in the nineties with the ill-fated FMV genre. The sheer scale and prevalence of this within the medium meant it came to be seen as a positive for games to be described as ‘cinematic’, a word now trumpeted by every major publisher as the ultimate praise for their products, and many games strive to achieve that label by comparing themselves to whatever films are popular with genre crowds at that moment. The pinnacle of this current trend of cinematic storytelling is Naughty Dog’s The Last of Us, a game with incredibly high artistic aspirations that presents itself as the ultimate cinematic zombie story (the genre in vogue back in 2013). It’s pursuit of these ambitions makes it rather fascinating, as it may be the least interactive story I’ve ever played.

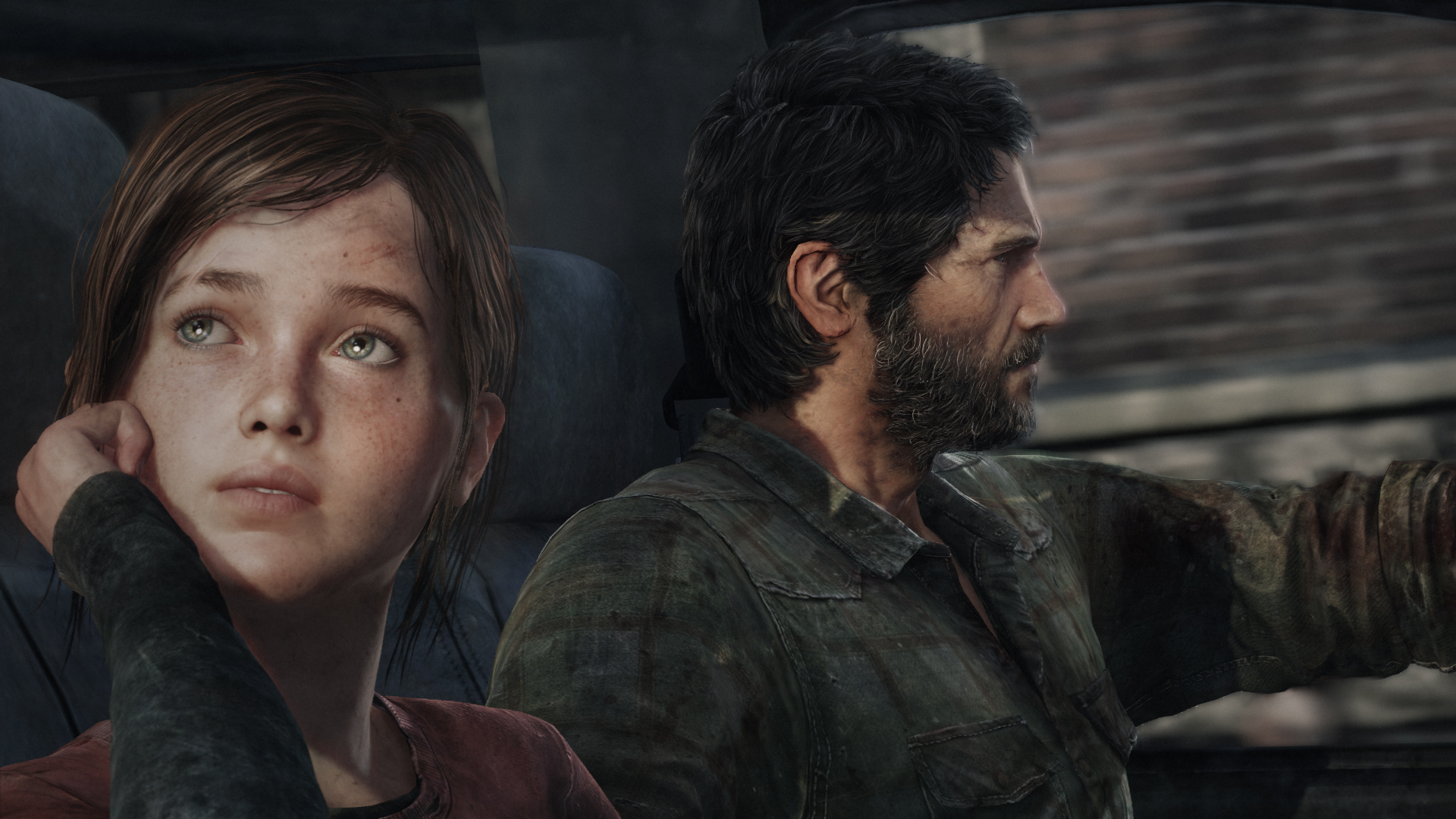

The Last of Us is the story of Joel, a smuggler in a post-zombie apocalypse wasteland who is hired by a resistance movement to smuggle a girl called Ellie, who is immune to the virus, across the country to their secret lab. The story’s main focus is the relationship between them, which is initially antagonistic but over time Ellie begins to view Joel as a father figure and he sees her as a surrogate daughter (his daughter died in the initial outbreak).

For the vast majority of the game the player plays as Joel, with Ellie as a bystander he is supposed to protect. This means the player’s arc throughout this should mirror Joel’s as they go through the same journey, becoming more and more attached to her so that by the end they should have trouble letting her go. But the game refuses to let the player actually act out Joel’s story. Between the prologue and the final level story and gameplay are completely segregated, with every story beat taking place in cutscenes outside player control.

The result is that the story which is the game’s main purpose in existing takes up only a quarter of it. It also means that every action Joel takes which comes to define him as a character is completely detached from the player’s experience, and they never come to fully identify with him as his actions are emphatically not theirs. It’s finally cemented in the ending, where after a whole level of shooting Joel takes the action which frames his entire arc and character in a cutscene without any input from the player.

At the end Joel decides he can’t let the resistance sacrifice Ellie to save people from the zombie plague (it’s never made clear if Ellie consented to this or not), and the player is supposed to kill them and doom the world because he can’t let her go.

online pharmacy purchase elavil online best drugstore for you

The game wants to have the player commit actions they feel are morally repugnant but inevitable, but unlike Spec-Ops: The Line it spends no time getting the player to share his motivation by having them live his journey. It simply dictates the player’s motivations to them, expecting them to fall in line. For the player there’s no reason to feel they have to do any of this besides just wanting to finish the game, and when that’s the only concrete motivation the player has you’ve failed as an interactive storyteller.

The Last of Us really seems intended to be viewed, not played. It’s refusal to let the player have any control while its story unfolds feels like it actively resents having to put up with a player. The experience is akin to playing a tabletop RPG with a really pushy GM, who holds the players up so they can tell the next part of the plot exactly how they want to out of fear the players will mess up their perfect story. The actual levels are less a means of progressing the plot than simply jangling keys in front of the player’s face so they don’t get bored. The worst examples of this occur at a friendly settlement in a dam, when bandits attack out of nowhere in a complete non-sequitur so the player can shoot something for five minutes before the story resumes and pretends it never happened. Shortly afterwards Ellie briefly runs away, and while Joel looks for her on horseback he is shot at by everyone he rides past for no discernible reason, just to add tension to a level so scripted it may as well be a cutscene.

The entire gameplay style of TLoU is antithetical to the story it wants to tell. The game is in the vaguely defined ‘action-adventure’ genre, which here means alternating between gunning people down like John Rambo and sneaking up behind them to choke them out. The story however is low-key and personal, so the constant jumping between small character drama and over the top violence is extremely jarring. The game has no non-violent ways for the player to interact with NPCs, besides brief superfluous sections of pushing Ellie on a float across water, so it’s impossible for the player to interact with other characters like a human being.

The game tries to justify this by saying that Joel is unable to solve problems non-violently, but it’s really emblematic of Naughty Dog’s inability to do that. When the player controls Ellie she is exactly the same, and spending an entire level as an untrained fourteen-year-old massacring scores of battle-hardened cannibals like John Wick is just downright surreal. When every character is extremely violent it becomes hard to see any character as appreciably more violent than anyone else.

The conventions of the genre also mean characters don’t react to violence as it happens. Ellie is incredibly nonchalant about all the brutal murder done in front of her, and when she starts killing people like the T-800 she displays an equal dearth of emotion, only to suddenly burst into tears in a cutscene after killing the cannibal leader. Trying to examine the realistic effects of violence on a character, as this game intends to do, does not work in any existing videogame genre based around violence. For the gameplay to focus on that it requires the violence to be depicted as a reliably repetitive pattern of events with a specific logic and temporary consequences, which is the opposite of how chaotic real-life violence works. You can’t examine the effects of violence on a character when they can be shot twenty times in a firefight and survive by patching themselves up in a few seconds behind cover. The only way a genre like this can examine violence is by examining its own genre’s depiction of it, as with Spec-Ops: The Line.

The Last of Us’ rigid adherence to genre also undermines its attempts at worldbuilding. Its title implies a world in which humans are few in number and dying out, but the game’s need to fill its levels with enemies means you run into them everywhere. The lack of non-violent conflict resolution means the game only populates itself with villainous NPCs who can be killed without troubling the player’s conscience. This leads to the strange situation that the player encounters at least a hundred bandits over the course of the game, but only two other travellers who they might ostensibly try and rob. It gets especially ridiculous when the player finds a large cannibal community in an inhospitable frozen forest, who apparently subsist entirely on the huge numbers of visitors it would take to feed them.

Like with Tomb Raider, there an ostensible major theme of survival running through TLoU, but one which is never reflected in gameplay. In games survival consists of the player relying on and exploiting their environment to survive, but here their sole means of survival is by either killing or avoiding everyone in their way, resulting in the same level of survival gameplay as Call of Duty. The environmental interaction is limited to continuing on the scripted, linear path the game sets for them or picking up items to craft weapons with to kill more people. The game’s linearity also undercuts the story’s presentation of Joel and Ellie having to find their way through a dangerous landscape. It never feels like the characters are having to explore or navigate their way through the world as there a single clear path from beginning to end. There are a few brief points when the game slightly opens its levels up and in these moments the world starts to come alive, but they are few and far between.

The game also completely fails to convey Joel protecting Ellie within the gameplay. While playing as Joel Ellie is both indestructible and invisible to zombies, and makes a massive racket while ‘sneaking’ in Joel’s wake. All this serves as a constant reminder she is not a vulnerable human but a digital avatar designed primarily to not get in your way. While escort missions are generally looked upon as a blight upon videogames (for good reason), the story Naughty Dog decided to tell is one that can’t be adequately conveyed by anything else. If you can’t find a way to properly convey the main thrust of your story in-game you should probably pick a different story.

The real source of games’ obsession with movies is that games have a massive inferiority complex when it comes to film. They desperately want to see themselves as its artistic equals and so have formed a cargo cult mentality, in which the aping of cinema is seen as automatically artistic and so the closer you can get to recreating a movie the better your game is seen as. Most popular games simply lift their stories from films: Resident Evil is George Romero’s zombie flicks, the early Call of Dutys were Saving Private Ryan crossed with Enemy at the Gates, and Uncharted is Generic Hollywood Blockbuster: The Game. The Last of Us mashes up every popular zombie or post-apocalyptic story from the past two decades, from The Road to The Walking Dead to Children of Men (from which it even borrows its font), and sticks so rigidly to them in its imitation that it struggles to find time to do anything new. It’s so focused on its ideal of becoming a movie that it comes off like the medium’s Buffalo Bill, wearing the skins of films to convince itself it has artistic merit while asking itself in the mirror “Would you watch me? I’d watch me.”

Lifting story elements wholesale from movies also tends to render them devoid of the meaning they had in the first place. This is a common problem in genre fiction, in which creators copy a groundbreaking work’s textural and aesthetic elements but not what they represent. The best example is probably just how fresh and deep the Lord of the Rings movies felt despite decades of inferior knockoffs having run the books’ style and setting into the ground before they came out. The elves, dwarves, wizards and hobbits in Tolkien’s world all represent something vital to the story, but in games like Warcraft they exist solely because that’s what Tolkien did. The zombies in The Last of Us are equally devoid of purpose, representing nothing but the writer’s fondness for the genre. If Ellie was immune to another type of plague the overall story would remain unchanged.

The main problem with trying to tell videogame stories cinematically is that gaming lacks the tools to do this. Editing, acting and cinematography are not available during gameplay because they are all interrupted by player control, so any story told by a game in a purely cinematic fashion will falter compared to even a mediocre movie. Stories in games do not work like stories in films. The player is not just watching the protagonist, they are the protagonist. I am supposed to be Joel, just like I am Captain Walker and The Nameless One and Wander, but unless I can act out their stories I will never become them.

online pharmacy purchase symbicort online best drugstore for you

Varying the amount of control the player has over the story is the most powerful tool a developer has to tell it (Life is Strange is a masterpiece of this), but if the player never has any to begin with they can’t become part of the story.

This is not to say the evocation of film in games is inherently bad. Taking influence from outside your genre is necessary to prevent it stagnating, and post-modern medium blending can lead to great things, but you have to integrate your influences into the medium you are working in. Until Dawn and Heavy Rain used cinematic language to tell their stories, but both adapted this to work in the videogame genre by giving the player control over the ‘cinematic’ sequences. Their storytelling was centred around player choice, allowing the player to (consciously or not) influence the story, making their actions truly mean something within the plot and making the game fundamentally the player’s story. The Last of Us however does nothing of the sort, steadfastly refusing to make its story in any way interactive.

There’s a fascinating phrase I’ve heard in relation to this game and others from critics, which is ‘gaming’s Citizen Kane’, and it really speaks to the mindset behind the exaltation of this idea of videogame storytelling. Citizen Kane is important to cinema because of the incredible breadth of its influence, inventing or popularising a wide variety of cinematic techniques that would go on to become standard. This is also obviously a reputation it could not earn until a decade after its release. However the film has stuck in the public consciousness as a synonym for artistic greatness, and morphed into the idea of a singular great work that immediately gives an often less regarded medium genuine artistic legitimacy (Watchmen was described as such). The problem with this is both that the idea of a single great work suddenly giving its medium artistic credibility is bollocks, as every work is built upon its artistic influences, and that as Kane is the comparison point this statement tends to be used to hold up works that can be easily compared to movies instead of ones that make the most of their medium. The Last of Us has nothing in common with Citizen Kane. There is not a single new idea or technique within it, the story is a pastiche of others without remixing its ideas to form something new and the methods of storytelling and style of gameplay are just the generic third-person shooter conventions Naughty Dog used in Uncharted. What gaming needs is not a game to suddenly give the medium artistic legitimacy, which it has had for decades, but games which push the boundaries of what only videogames can do. Gaming doesn’t need its Citizen Kane, it needs its Man With a Movie Camera.

I think The Last of Us best serves as an example of why we desperately need new ways to tell stories in videogames. Almost all the genres we have are completely incompatible with the vast majority of human interactions, and the focus on violence as the central mechanic prevents them from being able to tell the sort of low-key character drama The Last of Us aims for. The first real step to unlocking the true storytelling potential of videogames will be the elimination of cutscenes, which are telling parts of a story in one medium using a completely different one without any attempt to combine the two. They’re what you do when you don’t know how to tell your story in your chosen medium, as title cards were in old silent films. Like those their use will never go fully away, as many modern films use title cards creatively in ways which enhance their storytelling, but there’s a reason they’re sparsely used these days. Ultimately The Last of Us’ problem is that of laziness, assuming it can coast by on its characters and plot instead of working to engage the player within them. It’s an evolutionary dead end, unintentionally serving to illustrate everything wrongheaded about modern videogame narratives. There’s an incredible future in interactive storytelling waiting for us out there, but The Last of Us isn’t it.