Martin Scorsese’s The Irishman has been one of the year’s most anticipated movies since the day it was announced, but the discourse surrounding its release has been focused on a things that have absolutely nothing to do with the film itself. It is almost easy to forget that we’re dealing with a new crime epic from a master of the genre starring a murderer’s row of amazing actors. Luckily, The Irishman is great enough – and packs such an emotional wallop – that if you’re still concerned with what it’s director thinks of comic book movies by the time the end credits roll, you definitely need to either watch more movies or go outside more often. Preferably both.

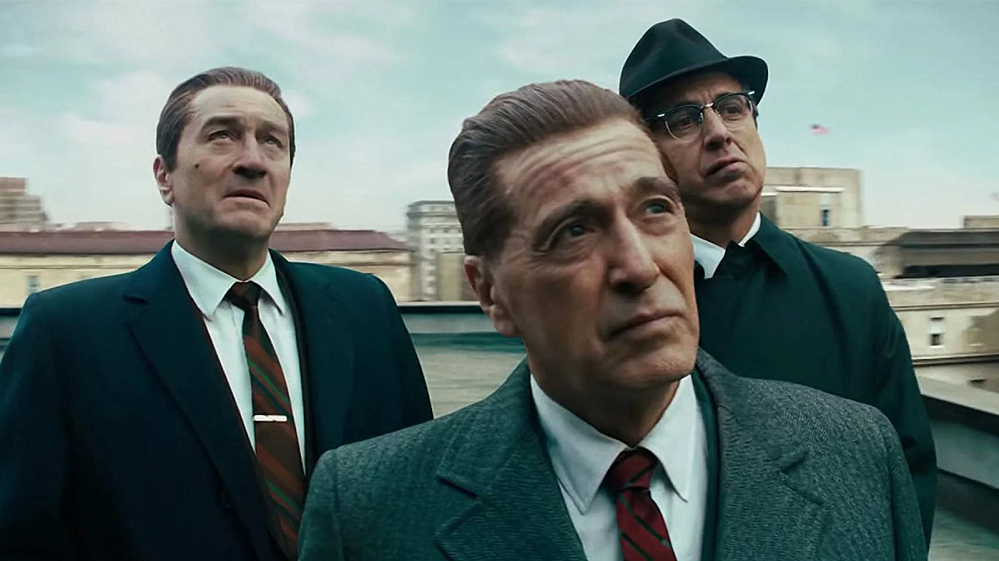

In 209 minutes, that honestly fly by, Scorsese and screenwriter Steven Zaillian tell the true story of Frank Sheeran (Robert De Niro), the titular Irishman. “True” probably needs to be in scare quotes there, as the story Sheeran told to investigator Charles Brandt — who wrote the book I Heard You Paint Houses, on which the screenplay is based1 – has been heavily disputed. The film positions Sheeran as sort of a Criminal Forrest Gump, who, after a chance encounter with Pennsylvania mob boss Russell Bufalino (Joe Pesci, returning from retirement from the first time in nearly a decade), becomes a key player in mob history, being on the wayside during all sorts of pivotal moments, including a friendship and partnership with Teamsters president Jimmy Hoffa (Al Pacino, working with Scorsese for, somehow, the first time).

In typical Scorsese fashion, Frank narrates large swathes of the film directly to the viewer. In less typical Scorsese fashion, he does this as an old man in a retirement home, seemingly rambling his story to an audience of no one. That’s also where the film starts, with Scorsese treading the camera through the facility’s grey halls and past the slowly walking elderly in a tracking shot that knowingly contrasts the Copacabana shot from Goodfellas from minute one. If that didn’t make it clear enough that this is a film focused on aging, the remaining 207 minutes certainly will.

The much-ballyhooed CGI de-aging tech used to make De Niro, Pesci and Pacino look like their young selves also adds to this, at the same time distracting from their ages and drawing attention to it.

The actors still walk like old men and, especially in De Niro’s case, still have the eyes of old men. It’s a somewhat flawed illusion, but seeing as that we’re getting the maybe-not-entirely-accurate reflections of a man nearing the end of his life, it works nonetheless. And while the first scenes showcasing the de-aging are certainly somewhat jarring, after a few minutes it becomes near-seamless.

Once the effect has settled in, you’ll be able to enjoy the acting to the fullest, which shouldn’t be hard as everyone involved is at the top of their game, especially the main trio. It’s been a long while since any of them have excelled this much on the big screen. Pacino gives the showiest and most attention-catching performance, commanding the screen from the minute he shows up about an hour into the film. It’s a very loud performance, as is typical from late-period Pacino, but there’s more grace to it than usual, with the actor also shifting to a more slumbering and subdued mode of acting in key scenes.

That said, it’s his many outbursts that will likely prove to be the most memorable, especially one scene about halfway through the film where Hoffa goes on a “COCKSUCKAH” leaden rant that gets so intense the character has to take a break in the middle to catch his breath.

With Pacino eating all the ham sandwiches available on set, Pesci and De Niro are allowed to go quieter. A lot quieter, which is especially relevatory in the case of the former. Bufalino never once loses his temper and Pesci imbues the character with a soulful melancholy at all times. This especially comes to the foreground in the scenes where he tries to play a nice, elderly uncle to Sheeran’s daughter Peggy (Lucy Gallina/Anna Paquin), who is mostly scared of this man she perceives as an obviously mean mobster. That he has Joe Pesci’s face certainly doesn’t help. You keep waiting for Pesci to go full Tommy/Nicky, but it never comes. Much like the previously mentioned opening shot, Scorsese wants to remind you of his previous crime sagas, but he’s not interested in merely rehashing them.

He’s toying with our audience’s lizard-brain expectations.

De Niro has the least “exciting” part on paper, with Sheeran just being a bystander for a lot of the films events, as well as someone who is happier following orders than chasing any agenda of his own. But De Niro makes it sing, delivering a sad and soulful performance that’s the best he has done in years. A late in the game scene where Sheeran has to make a phone call following a devastating event ranks among his career best, as do many other scenes in the final half hour.

Because, oh, that last half hour. While Scorsese is in a contemplative mood for the entire running time – no semi-jovial outbursts of violence set to an ironic soundtrack to be found here as every violent scene is punctuated by horrified bystanders – it isn’t until the frequently harrowing final thirty minutes that he really zeroes in on the film’s theme of mortality,2 delivering a final stretch so obsessed with death it would make the Coen Brothers3 blush. After the sprawling, decades-spanning first three hours, the film focuses almost exclusively on Sheeran and what his life has done to and for him in the homestretch. The final scene and shot in particular are heart-stopping.

While the entirety of The Irishman is very compelling and exudes superb craftsmanship from everyone involved,4 it’s the denouement that really sends it into the stratosphere, turning a great greatest hits album of a movie into one of the year’s – and its director’s – very best.

- And with which the film seems to share a title, I Heard You Paint Houses appears on screen twice, at the beginning and at the end, while The Irishman only makes a perfunctory appearance at the start of the credits

- Which is also hammered home by the title cards that accompany the introductions of a lot of supporting characters, telling you exactly when and why they died. Most of the time, it ain’t pretty.

buy zoloft online meadowcrestdental.com/wp-content/themes/trash_themes/meadowcrest/imgs/zoloft.html no prescription

- Whose The Ballad of Buster Scruggs is a closer point of comparison than you might think

- With editor Thelma Schoonmaker, of course, deserving lots of praise for making this potentially highly unwieldy thing move like Swiss watch