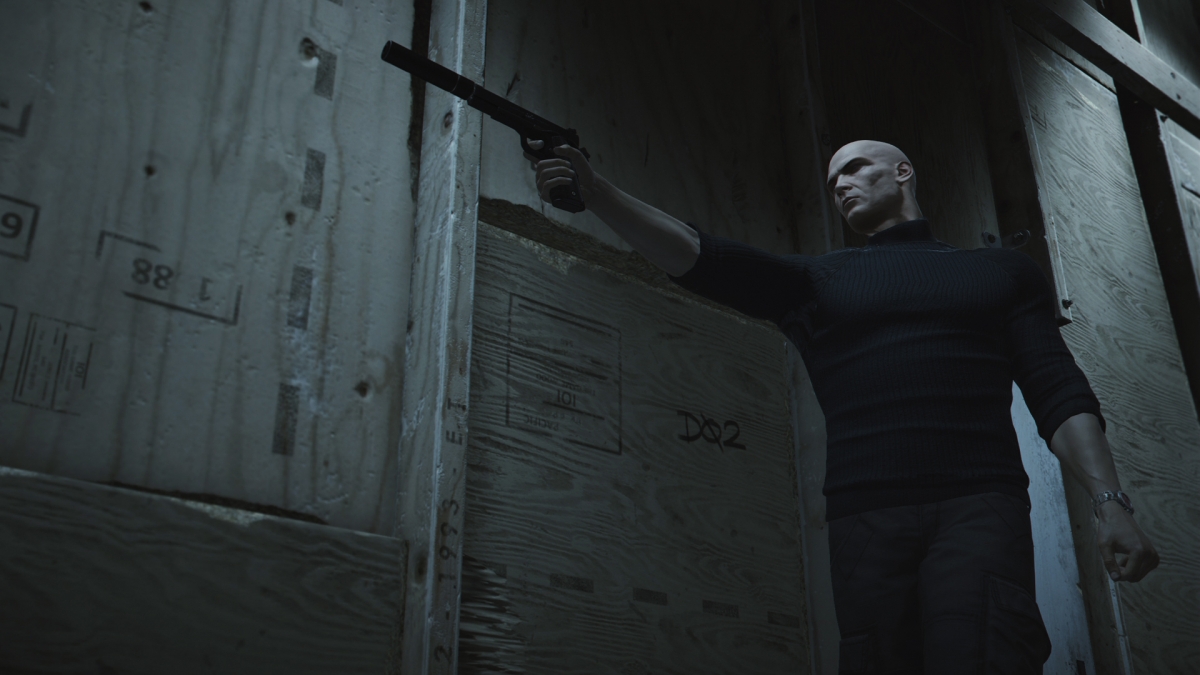

Killing people in weird and wonderful ways has long been a staple, and sometimes the central foundation, of videogames and Hitman is no exception. In this long-running series of puzzle games by IO Interactive the player assumes the role of Agent 47, a genetically modified super-assassin given special powers by his 47th chromosome (according to the first game), as he travels the globe murdering people in various holiday spots. The game presents large, open-ended levels full of civilians just milling around on their day jobs, and allows the player to exploit and kill them to complete their mission.

It lets you stab waiters, garrote actors, poison people at random and if you get bored simply machine-gun your way through a packed crowd like a grumpy American white boy with a grudge. So why won’t it let you play the villain?

The premise of Hitman seems tailor made to do away with plot entirely. 47 doesn’t kill people because he needs money or to avenge his loved ones, he does it because it’s his 9-5 job. But every game goes to great lengths to present the player’s actions as ultimately heroic. Each mission has detailed backstories for all its targets, explaining why they are the worst person since Donald Trump and so are deserving of a violent and embarrassing end. Even at the climax of Hitman: Contracts, when the target is a police chief introduced in that mission attempting to arrest 47 in a recreation of the end of Leon, he still gets an extensive, corruption-filled backstory to justify his death. The only exception is an innocent journalist the player kills at the end of Hitman: Blood Money, who’s been manipulated by the villain to tell the world about 47. But this is framed as collateral damage during the killing of that bad guy.

The game’s terrible overarching plots also exist to place the player’s actions within a larger context of being justified in preventing even worse outcomes. These usually take the form of a villainous organization attempting to clone 47 or create or control similar GM assassins, with which they will wreak terrible death upon the world (which is of course completely different from the terrible death 47 wreaks upon the world).

Games placing their players in the role of a villain are pretty common, but they always undercut their protagonist’s villainy in some way. Destroy All Humans, Overlord and Evil Genius all star supervillains attempting to enslave the world or probe human anuses, but their overtly comedic tones sand off any unpleasantness. The consequences of your actions are rarely dramatized and when they are it’s as a joke, preventing you from ever empathizing with your victims. Games like Grand Theft Auto and Prototype present their protagonists as antiheroes fighting off villains far worse than they are, and while the main character may insist they’re only in it for selfish reasons they still inevitably save the day before returning to their Batcave to brood.

Recently there’s been a trend in games of initially presenting the protagonist as the hero of the piece but revealing them to be the villain over the course of the game. Spec-Ops: The Line is the best example of this, ably manipulating the player so that they slowly fall into villainy without realizing. As the player goes on they desperately cling to their belief that they are the morally upstanding hero of the story, and it’s this that drives them to commit more and more heinous acts attempting to accomplish their goal. This still requires the player to be presented as the hero for much of the game though, in order to get the player invested enough to still want to continue after realizing they’re the bad guy.

Torturing innocents in games is a time-honoured tradition among players, to the point where stabbing prostitutes in GTA is not only accepted but expected. But games that let you do this never admit to encouraging players in this way, because the thrill ultimately comes from a feeling of transgression. Games like GTA ostensible dissuade and condemn the player for harming innocents, putting on a show of attempting to stop them by sending armed police after them. Even though the game is tacitly egging them on the player gets to pretend they are subverting the established order and disobeying the game’s intentions, instead of playing into them. You also see this in RPGs with moral choice systems. Choosing pointlessly harmful options triggers a ‘bad karma gained’ message and a dramatic musical sting to let you know the game disapproves of your actions. If the game explicitly tells the player to kill every innocent they see, like in Hatred, it becomes very boring very quickly.

The only game I know of that presents its protagonists as unambiguously villainous throughout while maintaining a serious, unpleasant texture is Kane and Lynch 2. It is a terrible game. The shooting is monotonous, the plot aimless and the attempts at adult subject matter alternately silly and nauseating.

online pharmacy purchase wellbutrin online best drugstore for you

But it really goes to show why the player can’t be a full on villain.

Kane and Lynch are both remorseless murderers trying to broker an arms deal in Shanghai, which inevitably goes wrong leaving them at the mercy of a poorly-defined crime boss.

The problem is that their motivations are never in any way relatable. They want money and are willing to do all sorts of horrible things to acquire it, but there’s nothing for the player to get out of this.

online pharmacy purchase clomid online best drugstore for you

They won’t be able to do anything with the money even if they acquire it, and there’s no human connection to any other characters besides Lynch’s wife, who appears very briefly to be killed.

Even if you promise the player wealth and power for their evil deeds it means nothing without a tangible connection to the world of the game. Exercising power is only fun if you care about what you’re exercising it over, and fictional money is only as interesting as what it buys. The real problem with being a straightforward villain in a game is that evil for evil’s sake is boring. This is why we start losing interest in films whose villains have no reason for their actions besides being villainous. Ultimately Hitman needs to have a story to morally justify the player’s actions, no matter how threadbare or awful it is, in order to be compelling and let us enjoy it guilt-free. People need validation to indulge their worst impulses, as the thought that you may actually be the bad guy can be utterly paralyzing. We see this all the time in media: Transformers goes out of its way to normalize its love of objectified women and violence to the audience, and Bond has always had Moneypenny acting above his advances to reassure the audience that he’s not abusing women. But stripping this away removes the fun. When you get down to it there’s a real banality to evil.