For a review of You Were Never Really Here, please read Kevin Kuhlman’s take on it.

Warning: Spoilers Abound

At first, something eludes us in the silhouette’s actions and demeanor. Its pace seems too erratic for the camera to capture, and too swift for our mind to properly register. As an interwoven fabric of sound and whispers from the past, counting back from 40, present and future gets to the folds of our brains through the cracks in our ears. Lynne Ramsay has us leaning towards the screen, incredulous, and fall into the instinctive responses of our own triggered nerves.

When the optic settles on a hotel room, things are happening fast. Something violent may have occurred and some blood on a hammer is the first clue that something may well be still pursuing its unusual course. As sight is troubled, thrown off-guard, by pulsating close-ups, sound gives us glimpses of indoor clapper and something akin to cinematic instinct confirms us, the listener, that someone is pursued, or pursuing someone. As the first on-screen burst of violence is administered to our protagonist, it anchors everything and everyone.

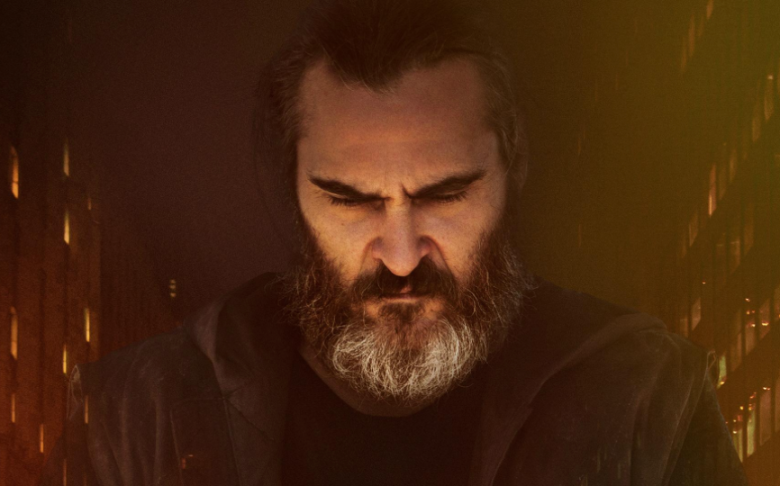

Joaquin Phoenix comes to a halt, impacted yet unmoved. He answers accordingly, striking his wimping opponent with a single blow that knocks him on the ground, not allowing him to stand again. We finally get a first look at the rock of flesh and hair. He chiseled his being into Joe, a war veteran, who does some wet work for undisclosed clients to pay the bills and help him take care of his aging mother. You might be confused by the protagonist of You Were Never Really Here but this confusion of sound and images, present and past, is the very fabric of his own being here.

Three Synthesizers

Joe is a man of habits and principles. He lives with his mother who he cares for, and about. It’s a funny thing for a verb to both mean a passive state and the pursuit of active habits in the craft of everyday routine. All it needs is the added preposition to be cast into the actuality of the present. Joe, he has issues with the actuality of the ever moving present. Plagued with sudden bursts of audio-visual violence, the real happens to him with the traumatic remembrance of past events. He’s never fully focused on the moment and therefore is not always focused on by the camera. The fabric of the film is made of ruptures, breaking points, interruptions both in audio and visual. Sounds of the outside are faint, distant and compressed by the haunting score of Johnny Greenwood, until the world refuses to let Joe’s past own him again. The outside world makes itself known with clattering crowds, tinkling beeps and swishing cars. the world swells out of a sound design that is beyond anything else I’ve heard this year, echoing Joe’s own mental and physical ripples. He walks around, not with a limp, but with difficulty, somehow. Things are happening fast to us, because they are happening fast to him now. We have a hard time catching his actions, until he walks off again and the camera is pushed out of a car seemingly by the screeching of a duct tape.

Joe gets distracted by cars, the TV, the radio, children who know where he lives (though they shouldn’t), the pseudo-iterative routine of his mom that is losing her own grasp on reality. Nothing is more real to Joe maybe than the inner drum of his own off-kilter, stuttering, traumatic memories. The foot of a dead child in a no man’s land. His own whispers as his father hunts him down with a hammer. His mom’s glasses, stained with blood then, stained in her last blood now. The sound editing of the film echoes not only what Joe hears, but what ripples the outside world makes to his fatigued and swollen face. The world is hitting him hard; it has been since he was young, and all he can catch are moments of breath in air-less lakes. The blinding sunlight, though serendipitous, bites his purple face. Extreme close ups seem to up the existential traffic of murmurs to eleven.

clattering crowds, tinkling beeps and swishing cars

Three harpsichords

The sound editing is superb, but the soundtrack that has been accompanying me from outside of the theater since I downloaded it is nothing but haunting. A composition of rhythmic beats and dreamlike tremor that evoke walking at night in the city, preparing a hit. It often makes us believe that we found a ground to settle, and a pattern to it, until the composer unsettles the rhythm of the piece, bringing an out of whack drum that is just a little wrong. Chords are sometimes struck in an unusual bunch. Sometimes they are hit, improperly, as to create music without notes, a cacophony that greets the violence, until they are brought to perform their highest pitch that highlights the aftermath. Synthesizers contaminate the city, strings erode the interiors of a family home, and harpsichords crawl. With them, we see the images of some wealthy owner of a devilish doll’s house filled with paintings of eroticized young girls.

Joe could end it all. The PTSD. The routine and the impossibility of actualizing the present. He stabs, hits and strikes not out of a will to survive, but out of the need to save the ever-traumatized he sees in the victims he’s paid to save. This little girl is being held in a big house, filled with pedophiles, not too different from the house he’ll try to save her from in the end, not too different from his childhood house. This sexualized little girl does not know how to say “thank you for saving me”, other than by offering him acts that have been made to her in the most deafening violence that is not pictures, merely hinted at.

He refuses it immediately. She counts backward, out loud as she has been since the beginning of the film, thus lulling us back to our reality as the film ends

Her stare feels like his, lost on the wall, building make believe exercises, coping mechanism, and magical thinking tools that help her get away from the real by slowly connecting her back to the present. Something I’ve myself used for years since I was a kid, avoiding the blows of my childish mistakes, overtaken by the violence of a world too big, too adult, too loud too scary, made of too much oversized realness.

The thunderstorm that inhabits Joe’s inner fury is but a fraction what awaits her, as the trauma settles in this mire of past and present.

Keeping his head in the plastic bag for just a little longer

Three strings

If he just leaned an inch closer to the subway, if he just let the man choking him finish the job, if he just kept his head in the plastic bag for just a little bit longer… It’s the ever calming thought of maybe ending it all by shooting himself, there might be comfort and, finally, the great quietness.

In one of Joe’s rare moments of clarity, towards the end, as he walks purposefully but slowly into the house of the rapist, he saunters, maybe knowingly, at the pace of the song that plays in the house, in an anchoring lull. There are moments of brevity that bring to the eyes and ears pieces of transitory resolution. Found in the routine of a green jelly bean preferred to others that he slowly smashes to a pulp by gently pressing it between his callous fingers. In counting backwards the seconds until she decides the thought of her own unraveling will disappear. In the indistinct chatter of the common folks. In the quiet bounding of two professional killers, one agonizing, the other mourning, whilst holding hands and chanting the 50’s pop-song on the radio.

And in the now saved child that gently pats Joe on the head as he dreamed again of ending it.

In the four milkshakes they ordered because it might be nice to try them all, half drunk throughout in the final credits, there could even be a future. But first, to help the listeners collect themselves, a little piece of unspoiled present.

A ringing sliver of solace