Ted Post’s Beneath the Planet of the Apes is my favorite of the original Apes series. It is in part an uninspired remake, in part a wildly imaginative and existentially desperate dystopian mindfuck. This film is fabulously weird and I’m going to take a few minutes of your time to bask in it.

This is an Actual Film Plot

I’ve spent almost an hour on the next four sentences, trying to wrangle this dumb hard ramen clump of a plot: a lone survivor of a spaceship crash on a dusty planet discovers a village full of upright talking Apes where humans are mute, un-tame, and enslaved. The apes on this ostensibly(but obviously not) alien planet imprison feral humans, whose intellectual skills seem to begin and end at loincloth-craft.

The stray astronaut, tediously named Brent, escapes the town with the help of a couple friendly chimps who are reprised from the first film, Zira (Kim Hunter) and Cornelius (wrongly played by David Watson while Roddy McDowell was off doing something far less important). Brent, thanklessly played by the otherwise wonderful James Franciscus, is a role that would forever be mocked as a spineless nice-guy mimickry of the first film’s hero, Taylor, who was a singularly obnoxious creation by Charlton Heston.

Not-Taylor and Taylor

Brent hauls off in search of Taylor in a storied, mysterious wasteland called The Forbidden Zone. (Of course it’s called The Forbidden Zone.

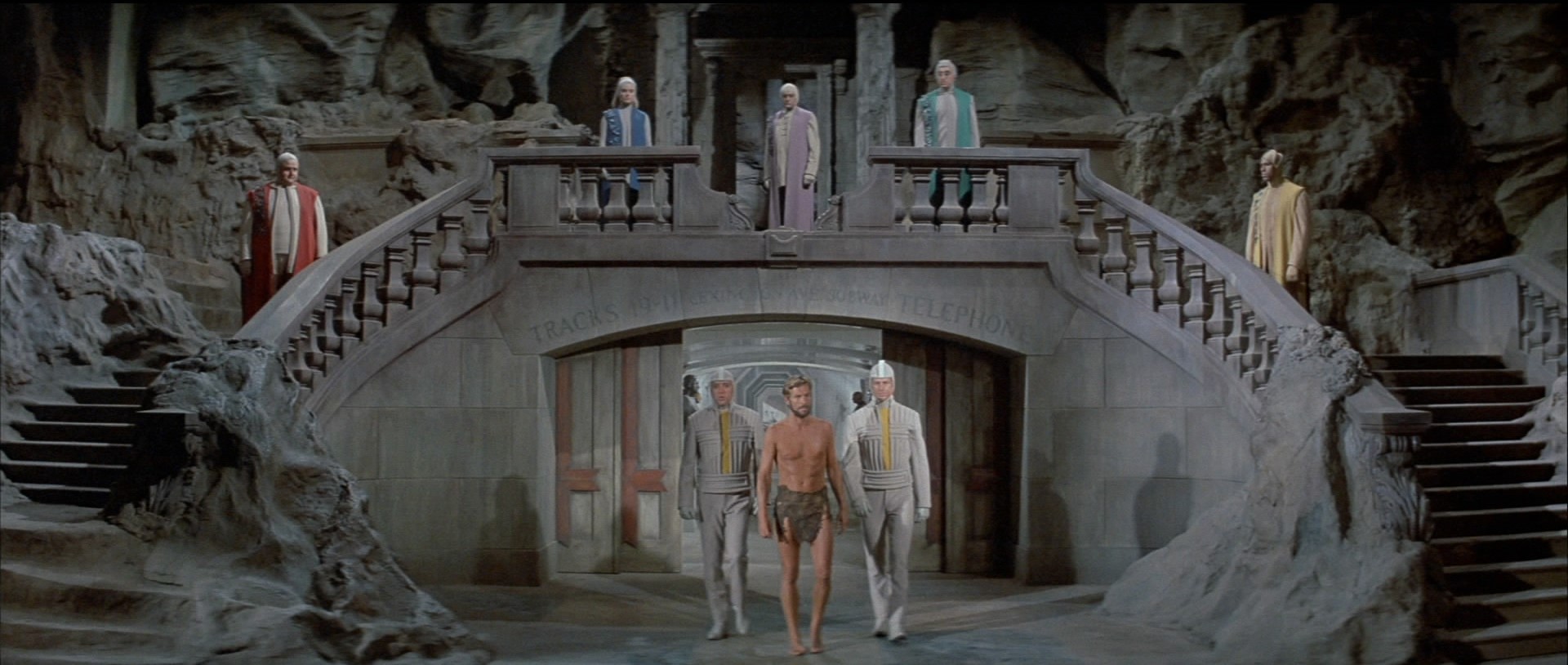

) He is somehow accompanied by Taylor’s female acquaintance Nova (Linda Harrison). They run into each other and join up presumably because the producers thought she and Taylor looked great on horseback, so she’s back here with lame not-Taylor reprising the same useless moves. Anyway. Brent finds Taylor imprisoned deep under the wreckage of New York City by a tribe of psychic human mutants who worship a massive, polished brass nuclear missile.

That last sentence is why this film endures. It’s fucking BANANAS.

From here-on-out I’m pretending that all of the ape village business doesn’t exist.

Matte paintings of sunken New York City landmarks populated by skinless veiny mutants who speak to each other via psychic beeps is all that matters.

Who needs skin anyway?

How Do Sequels Work?

I like the film because its detour into such deeply weird subterranean horror is unexpected. I like to imagine audiences and critics at the time wondering what the hell happened to their beloved, still young, franchise. To progress the series, however, the film couldn’t simply retell the previous tale, at least not in total. The original story is a landmark of speculative fiction, somewhat ridiculous in hindsight but in its day unlike anything else. Humans are frequently the villains in science fiction, and this was ultimately no different in Planet of the Apes. What surprised audiences, however, was the sheer hopelessness of Taylor’s discovery, the existential wallop with which he is hit at the (apparent) end of his story.

Beneath the Planet of the Apes one-ups it. And it utterly loses its damn mind in doing so.

The thing is, serialized film sequels weren’t really an established norm. There had been long-running series since the medium’s inceptions; low-rent horror franchises, sci-fi matinees, and more recently the Bond series. Only the Bond films could compare as far as big-budget, high-profile output from major studios. However, the Bond films were generally only united by their central character and a few very loose plot threads that primarily boiled down to the repetition of villains. Each film essentially starts from point A, as if the previous film had never happened. They are standalone, meant to be consumed like an episode of a sitcom or a procedural cop show.

From the outset, the Apes franchise designed each sequel as a direct narrative continuation of the previous film. This was unprecedented. Star Wars hadn’t yet come along and shown the world how elaborate film franchises could effectively expand their universes and stories from film to film, rather than deploying stand-alone adventures with little or no connective tissue. Planet of the Apes was a pioneer, but sequel scribe Paul Dehn didn’t quite suss out a successful technique until Escape from the Planet of the Apes and its direct followups. Beneath the Planet of the Apes presents a familiar tension between the desire to reproduce successful elements of a well-liked and profitable original film, and the need to explore new ideas. We see this all the time in sequels that replay story ideas that worked well in the past, even while they try to push ahead in new directions. Consider JJ Abrams’ Star Wars: The Force Awakens. The film is essentially a remake of the original Star Wars: A New Hope, told with (mostly) new characters and locations, and with Abram’s unique, signature tonal energy.

Good Luck Sleeping

I first saw this film when I was maybe 10 years old. This sort of thing makes an impression on a kid:

Sorry

The film is stunningly grim. All we really know about these mutants is that hundreds of years’ of radiation exposure and underground living have left them skinless, instilled them with the ability to communicate psychically, and so psychologically traumatized their generational DNA that they now worship a big brass doomsday missile, a nuclear bomb capable of annihilating the planet. This being the height of the Cold War, the notion that a human tribe has entered into a spiritual truce with the agent of its own doom is a relevant allegory of sorts. The bomb is God, not so distant from Dr. Strangelove and its cock-rocket. The fetishism of self-destruction.

In a nice bit of thematic reverberation, having concluded the previous film with his shocked protest that humans finally “blew it up,” Taylor himself has a go at blowing up the planet by the end of this film.

YOU MANIAC!

A Sonic Apocalypse

The mutant sequence is lively with inventive film-craft. Being who I am, I want to talk a bit about sound and music. As Brent and Nova probe deeper into New York City’s belly, a low drone begins to fill the space, first in painless, steady notes, and increasingly crescendoing into unbearably dissonant whines. This climaxes in a musical interlude in the mutants’ church of the bomb, an almost hilariously bombastic pileup of pipe organ chords and chorus. Though the hymnal tradition gives this piece much of its structure and tonal basis, its final shape is an absolute clusterfuck of incongruous walls of incompatible harmonies.

The mutants’ ear for music appears to have evolved along with their psychic abilities.

One of them nods his head, we hear a boop, and we are to infer that language has traveled to another’s head in some form. If their psychic communications sonically approximate a bunch of beeps and boops it stands to reason that their worship music gives no shit about our petty old world melodic structures. These are agents of chaos and, ultimately, existential annihilation; let them make sound that forecasts their roles in this absolutely bonkers universe.

This leads me to an observation about your filmgoing experience. Think about immersion in film experiences. Have you ever watched a film and been unaware that you are seeing what a camera sees, not what a character sees? Is there ever a question that characters’ eyes are over there somewhere, maybe onscreen at the moment, and the camera has its own point of view at all times? Visuals in film, unlike some video games, are never truly immersive.

Sound is altogether different.

As Brent and Nova suffer through these awful sounds, we do too. There is no awareness of a microphone. Assuming that your theater setup is reasonable, sound like this that crosses over into score at times exists in a realm of pure sound. Film music is typically extra-textual, which is to say, it’s typically beyond our characters’ perception, intended purely to guide our experience of a piece. These tones are diegetic score, music that both has an origin within the film, but that also contributes to our emotional experience. Such sound, unlike visuals, is truly immersive, is purely representative of characters’ point of view even as it convinces us to feel and respond a certain way to events on screen.

How is This Rated G

I saw this film by myself at a matinee when I was 10 because it is rated G. 1970 was clearly not thinking of the children. The entire series played over the course of a week, open to all school kids in the area who were out for summer vacation. I somehow missed the original Planet of the Apes but managed to marathon all four sequels in one week. This clearly isn’t the best of them – Escape from the Planet of the Apes and Conquest of the Planet of the Apes share that honor – but it is the most startling and somehow primally disturbing. I love the new films from Matt Reeves, but I can guarantee he will never risk the sort of tonal and genre twists that the original series delighted in. Stylistic unity in franchises just hadn’t yet come into being.