Aliens has been talked to death by fan culture. There’s very little I can say here to extol the virtues of James Cameron’s 1986 masterpiece of a sequel, but I would like to use this article as a place to discuss how its very nature as a modern classic has sort of ruined the film’s legacy. Put your pants on, because I’m about to talk about what we talk about when we talk about Aliens.

Taking place 57 years after the events of Ridley Scott’s groundbreaking Alien, this film again starts with a gradual title reveal. However, gone are the crisply designed lines of the original, slowly taking shape over a matte painting credit-roll. The lettering this time unfolds rapidly, forming itself from a pixelated spreading cancer. And like so many key moments in the film, it appears to us on a screen readout. Cameron’s intent in framing so much connective tissue and many early action scenes via viewscreen might normally be employed to keep viewers at distance, coldly observing as events unfold and characters are unceremoniously dispatched. However, showing so much through screens doesn’t remove us, but instead includes us with the marines. Makes us party to their fate. He shows us the POV of individual characters and illustrates the way they interact with their world, and discover it. In the case of Burke’s later betrayal of Ripley and Newt, Cameron actually turns the dynamic back on itself to illustrate the way we intentionally distance ourselves from our sins and compartmentalize them as happening somewhere else, hiding them with distance and obfuscation if at all possible. Hiding ourselves from the consequences of our actions.

But why is this important to discuss?

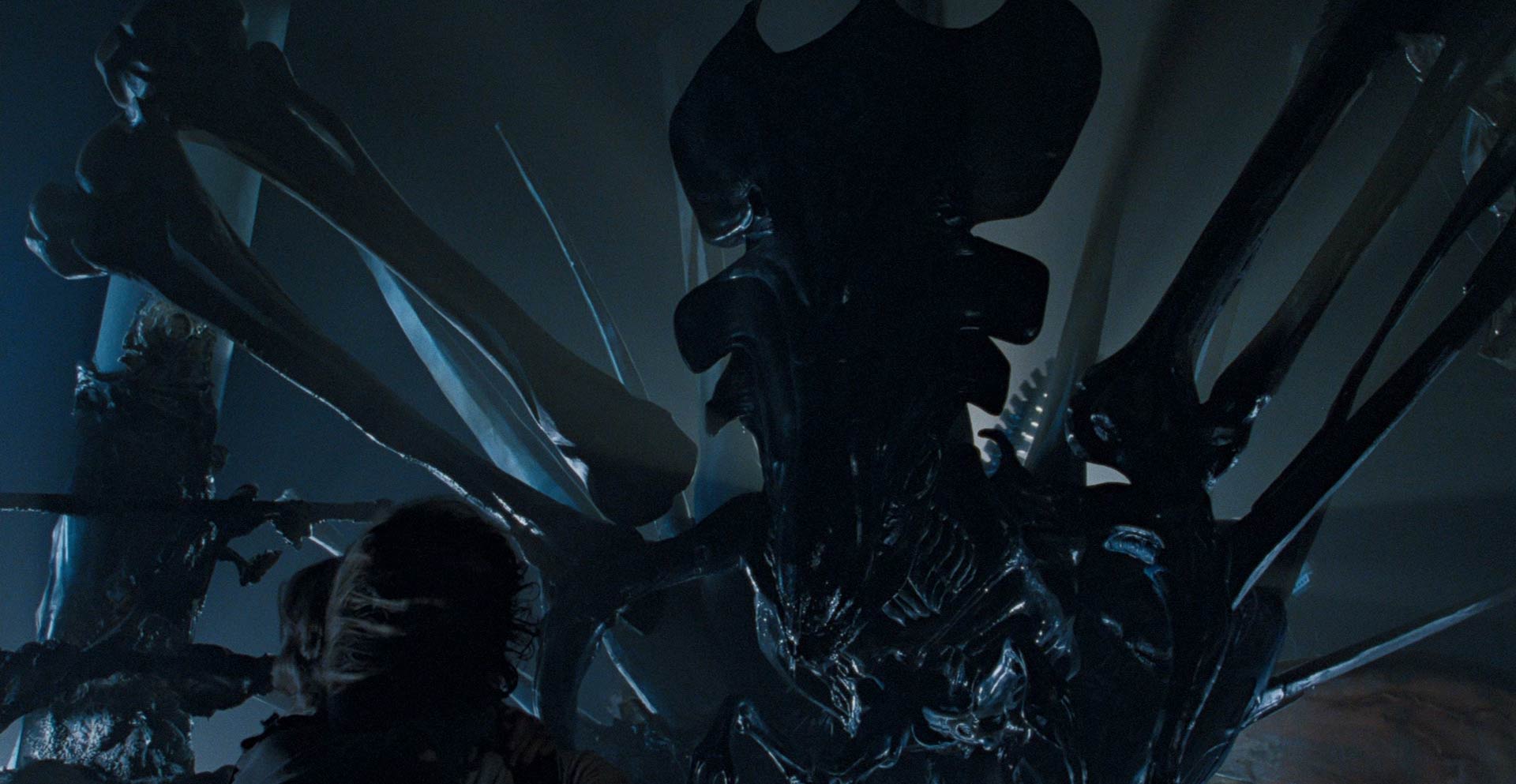

Because James Cameron created the perfect sequel, and an all-time classic film in its own right. The deliberate and purposeful way Cameron delivers information in Aliens is expert. Not a second of the original theatrical cut is wasted. The pacing ebbs and flows only a little. The steady tension and build of this film is constant, only swinging one micron back or forth when an important character beat needs to happen or a theme needs to land. The slow trickle of information regarding the source of the alien scourge on LV-426 is purely effective. A budding sense of mystery lies just under the surface of a steadily escalating siege film. The process of revealing the alien queen comprises a drip-feed of new data, until a crescendo of design and theme finally unveils the icon of terror (and patriarchal reproductive expectation), central to Ripley’s character journey so far. Finally, Cameron wraps us in her cathartic moments of earned triumph. Taking the reproductive theme from Alien and hanging it on motherhood, explicitly depicting the place of women in a man’s society (and genre), Cameron crafts a story of trauma and recovery. In the recorded images the characters capture of the colony, constant ruptures and shatters in interior structures mirror Ripley’s own psyche. Cameron is demonstrating the fragility of our structures, and the folly of placing our faith wholly in force and strength. It’s important to acknowledge Cameron’s tight control of craft in what was only his second major film, in order to draw a sharp distinction to his later work. This even hand and control seems to erode as Cameron’s directorial winning streak continues, and his films grow in indulgent bloat. James Cameron is a true populist filmmaker, with a finger ever on the pulse of what audiences want. But outside of (self-created) technical limitations related to his set pieces, what barriers have truly impeded his vision or output over the past 30 years? Can growth occur in a vacuum of challenge? Should creating or consuming art be limited to satiating desires? Which desires? If someone offers to serve you pizza for every meal, should you trust them with your health?

online pharmacy purchase temovate online best drugstore for you

The creation of a masterpiece inevitably invites curiosity and a hunger for more understanding. More discussion and consideration. But for some reason with genre-based art specifically, the creation of a masterpiece inevitably invites a hunger for more content. More tie-ins! More sequels! More spinoffs! More toys! Fill me with special features until I burst from consumption! My cup runneth over with deleted scenes! My variant covers tell tale of my endless devotion to… whatever. Almost none of this leads to any deeper connection with the original object we profess to have loved in the first place. Rather, the insatiable need to fill in all the little details with licensed and branded materials, and to revisit the artifacts we cherish with the added ‘benefit’ of revamped effects and tweaked dialog and newly-realized content long left on the cutting room floor (if it ever made it there to begin with), often diminishes and dilutes the uniqueness of those things we were once so drawn to. When Ridley Scott decided to show as little of the alien as possible in his film, he did so in service to the story he was telling. He and his team slaved over concepts and designs meant to evoke primal reactions of discomfort and terror within the viewer, which would be fueled by their interpretations of what they were seeing. When Cameron introduced a new element to the mixture with the Queen, he held back and offered only hints of her possible existence. He waited around 40 minutes into Aliens before seizing our dread and confirming what we already knew had befallen the new colonists of LV-426. Cameron followed Ridley’s lead from a place of deep appreciation for his craft, not simply a slavish devotion to the artifact he had created. He led with character, theme, and story rather than cranking the initial mix up to 11 and repackaging it with glossier effects. It didn’t last.

The director’s cut of Aliens does not ruin or erase the spectacular original. It’s easily still available in any format you wish to seek it out.

online pharmacy purchase priligy online best drugstore for you

However, it provides an object lesson in how fandom can ruin a thing. Fans of this series did not create this film, but the inherent need to kill our darlings did cause it to burst from the chest of the original. For whatever reason, James Cameron seized on an opportunity to create a vision of his seminal film that dares to embrace all of the very worst impulses in genre film appreciation. Bar none, every additional scene detracts from the whole of the experience.

A beautiful story of a woman choosing to build a life in the wreckage of what she’s lost, while taking vengeance upon the very concept of patriarchal motherhood and womanhood is reduced to a ham-fisted story explicitly about replacing the daughter who died when she was in cryosleep. The mystery and dread of the unknown fate of the colonists is utterly deflated with a tone-deaf introductory scene detailing their doom. Characters bandy about the thematic concerns of the films in insultingly bone-headed exchanges about battle, baby-making, and corporate profiteering. The addition of the scene involving sentry gun emplacements sacrifices steadily mounting tension in the central siege scene, lauded for ramping intensity and bravura battle editing; for kewl weapons shots. And finally, the mystery of the alien queen, so deeply intertwined in the thematic and character arc of Ellen Ripley’s triumph over trauma and gaslighting, is tossed away with a line so obvious it could have been written for a porn film. Harrison Ford’s voiceover in the theatrical cut of Blade Runner thinks this film is stupefyingly obvious.

When our minds are free to fill in all the spaces we can’t quite see, and guided by a craftsman exercising the correct mixture of control and release, we’re actively engaged in bringing the creator’s vision to life. We participate. What we ascribe to the images we’re consuming comes from within us, and is therefore more effective than thousands of artists working for thousands of hours to pump out fully exposed armies of creatures gobbling up our protagonists. What Ridley Scott knew is what Cameron knew. It’s also what he eventually forgot completely when taking part in the “director’s cut” of Aliens. The director’s cut is an exercise which destroys the very pacing, discovery, character development, and mystery that elevated what easily should have been a cash-grab followup to a beloved genre classic, into an essentially perfect sequel. I won’t ascribe motivation to this decision. I can’t parse what changed within Cameron, replacing his laser-focus on craft with indulgence.

However, I can easily point to a contributing factor in why we see this behavior become the industry norm over time: Us.

Think about some questions: Do you love Star Wars? Was that love of the original trilogy in any way strengthened by multiple revisions and special editions? Did the prequel trilogy enrich or inform your appreciation for those original stories? Have endless paperbacks filled with universe-shrinking plots actually made any of those films better in any way? What if you’d gotten 3 films, and nothing else? What if you’d gotten one? I’m honestly not drawing a line in the sand as some sort of arbiter of quality. I have been a party to this since I was a kid buying every Alien comic, paperback, video game, and piece of merchandise I could afford. Since begging to see every new film in the theater until I was old enough to take myself.

Since being a kid in the 90s desperate to see a version of Aliens with even one frame of extra footage. So what changed? There are now 6 films in this series. Of which I’ve seen 5. Of which 2.5 are what I would consider good films. I have every intention of seeing Alien: Covenant in theaters. I’m likely to re-read the Alan Dean Foster novelization of Alien within the next year. If one accusatory finger points at fanboys buying stuffed tchotchkes of penis-headed monsters, five point right back at me reading The Technical Guide To Aliens. But what I’ve come to reckon with in the 25 years since Cameron dipped into the George Lucas game of revisionist history, is that when you love something, your initial reaction to the spider-web of accessorized content should be at a default setting of distrust. My base hunger for any snippet, photo, storyboard, or tie-in novel related to this film inherently diminished what worked about it, once I came to trust my critical eye. I realized that when it comes to this kind of entertainment, more is often far less. Our need as fans to fill in every nook and crevice with explanations and side-stories and connective masturbatoria is the filmmaking equivalent of overlighting a scene. Illusion is destroyed. Suddenly, the tiny flaws on a set become glaring are no longer additive to a whole and special experience, but weaknesses we must shore up with banal backstory justifications. The object becomes representative of our tastes, and ourselves. We lose objectivity and define our worth by our attachment to what are ultimately trifles. And something sinister blurs our vision in defense of this gluttony.

My take on the artistic failure of serving fandom’s endless hunger will probably come across as harsh and naive, and I fully realize this viewpoint will likely be insulting for a swath of the audience for this series, and the broader realm of nerdery. I would have to be a real pollyanna to tell companies to stop making money by serving a market they created, and who are holding handfulls of lucre to have those desires met. But I hope if I get one point across in this piece (besides my lifelong admiration for Aliens), it’s that when we drive the properties we love into the ground, we inherently rob them of the qualities that drew us to them. Return to the well enough times, and it goes dry. I’d ask any who disagree with me here to reflect on the relative merits of sacrificing elegance of story for a few minutes of what boils down to padding. Is Aliens better because you got a button of Hicks sleeping when Apone demands someone wake him up?

Finally, I’d ask you to add your take in the comments.