Welcome to the sixth article in the Westerns 101 series on Lewton Bus. Here’s what you may have missed:

- 1. Introduction

- 2. A Bit of History

- 3. Defining the Western

- 4. The Essentials

- 5. Revisionism Before the Revisionists

When it comes to Spaghetti Westerns, there is Sergio Leone, and there’s everyone else.

That doesn’t mean the non-Leone filmmakers aren’t good, or that their movies aren’t worthwhile. Not at all. As we’ll see, there is some terrific stuff to be found in the genre. It’s just that the other directors are extremely different — in approach, in intention, in everything — compared to Leone.

But I’m getting ahead of myself. Let’s set the stage.

By the middle of the 1960s, the American Western film was beginning to run out of steam. The Western wasn’t dead, though. It had just moved to television.

The Lone Ranger premiered in 1949, but it wasn’t until Gunsmoke in 1955 that the wave began: Wagon Train, Have Gun Will Travel, Rawhide, The Rifleman, Bonanza, and literally dozens more you may or may not have heard of. Despite their period settings, they were easy to produce on a tight budget: Hollywood had been making Westerns for so many years there was an endless supply of backlot towns and standing-set locations, costumes, props, horses and accompanying experts, and more that the networks could rent for cheap. Most of the shows were built to recycle old-fashioned genre conventions week after week, occasionally mixing in elements of soap operas as their runs continued (some of these shows had astonishing lifespans). Only a handful were trying to do something a little different, such as Maverick, with a wiseacre hero who barely bothered to take his adventures seriously.

Hollywood was still making and releasing Western movies, but in response to the small-screen competition, the big-screen productions increasingly ramped up the razzle-dazzle. The number two grosser of 1963, for example, was How the West Was Won, an over-the-top extravaganza made more to showcase a new super-wide-screen multi-camera format and the producers’ ability to assemble an eye-popping ensemble of top-line talent than to say anything particularly new in the Western genre. In the same year, you also had 4 for Texas and McClintock, featuring all-star casts in lightweight comedy hybrids, and a variety of other half-hearted efforts. Out of this second tier, only McClintock cracked the top twenty in ticket sales, primarily because it starred John Wayne; most of the rest have been justifiably forgotten.

As the audience’s interest faded — or, perhaps, as its appetite for cowboy stories was satisfied by television’s weekly offerings — Hollywood shifted its attention to different story forms. Other top grossers in 1963 included the historical opus Cleopatra, the epic comedy It’s a Mad Mad Mad Mad World, the tail end of the box office for the first Bond entry Dr. No and the first two months of its followup From Russia with Love, the war classic The Great Escape, Hitchcock’s gleefully vicious The Birds, and romantic hijinks in Irma La Douce and Charade and the groundbreaking period romp Tom Jones. Master Western director John Ford was still working, but instead of a cowboy story, he took his favorite actor John Wayne to the South Pacific for the decidedly non-Western tropical trifle Donovan’s Reef. European films were also accelerating their push onto American screens, with Fellini’s 8 1/2 and Godard’s Contempt both making a splash.

That’s the cultural setting in which Sergio Leone made the movie that reinvigorated the Western, making it into a truly international phenomenon and breathing new life into it from an unexpected direction: 1964’s A Fistful of Dollars.

Europe Goes West

He wasn’t the first filmmaker producing Westerns in Europe. In fact, the Italian tradition of cowboy movies went all the way back to the silents, though it was more of an occasional dalliance than a sustained effort. In the 1950s, it was “pepla” movies, aka the “sword and sandal” adventures of Hercules and his ilk, that ruled the box office, but they were fading fast, and Italian producers were looking for an alternative.

Coming up on 1960, a couple of Hollywood projects had been doing some shooting in Spain, partly for the novelty, partly to save money; and then right afterward there was a small but successful run of German-made Westerns based on a popular series of novels. There was something in the air, and local movie people picked up the cue and decided to try to get in on it. Some of these first few European-made Westerns turned a modest local profit, but none of them was a major breakthrough until Leone’s film exploded across Italy and Europe in 1964.

What set this film apart from its predecessors? In my view, it’s due to two tremendous insights Leone had as he began conceiving the project.

The first could have come only from a European, or at least an outsider to American culture. For its domestic audience, the American Western was a reflection, however distorted, of actual history. The exploration and the taming of the continent — the building of the railroads, the frantic founding of frontier outposts by visionary pioneers and wild-eyed speculators, the subjugation and removal of the savage Indian — all of this was in the blood of the American people, taught in schools and reinforced by dime-store novels and traveling Wild West circuses. And as these established forms and philosophies began migrating to movie screens in the 1910s and 1920s, there were people alive who still had firsthand experience with the pre-settlement, pre-technological West.

In other words, as the “Western film” as a generic category took shape, it was heavily informed by its direct connection to literal living history. (John Ford liked to brag about how he got a lot of details for My Darling Clementine by talking directly to the real-life Wyatt Earp, for instance.) Now, mind you, it wasn’t particularly accurate history, of course; indeed, it was, whether consciously or not, a genre of historical mythmaking, taking recorded events and manipulating them, massaging them, in order to tell stories to Americans who wanted to feel reassured or proud about themselves and their national past. But even so, its appeal, and its staying power, came from the fact that the audience felt like the stories came from somewhere real.

A European viewer, by contrast, would look at a Western, and feel none of that. Their sense of history, obviously, is very different; no matter what country they were from, its frontier, its original exploration and settlement, had been completed hundreds of years before, if not thousands. They regarded the “cowboy movie” as a distinctly American genre, and they clearly saw Hollywood’s rewriting of history as self-serving, even when they didn’t exactly know the history being rewritten. Also, they wouldn’t pick up on any of the subtle background details intended to guide the audience’s perception of the characters (Civil War veteran? North or South?); as far as they were concerned, these were crazy stories of violent men pursuing each other through the outskirts of early civilization for primal, sub-rational reasons. The movies were still reasonably popular, though, because they were fun and action-packed and featured a unique setting that was a distinct change of pace. It was not, however, in any sense, perceived as authentic history; it was more akin to a Time of Legends, comparable to the tales of King Arthur and Merlin.

And that was Leone’s first major leap, and part of what set him apart from his early European contemporaries — he consciously abandoned even the pretense of honoring the genre’s traditional point of view on American history.

Essentially, in Leone’s hands, the Western was distilled into something like pure myth. The characters are not just experienced and highly skilled; their talents are otherworldly, bordering on mystical. They can control the story with almost supernatural ease, seeming to read their opponents’ minds, predicting future events with miraculous accuracy, and materializing out of thin air in a cloud of dynamite smoke. Their guns, especially, may as well be magic wands, with uncanny accuracy and unlimited ammunition. And it’s noteworthy that while the typical American Western will almost always make a nod at historical specificity in its setting — say, opening with a title card that says “Nevada, 1870,” or some such — Leone showed that wasn’t necessary. If the movie starts with a man on a horse riding into a small sun-baked village, you don’t need to know anything else; the particular where and when are completely irrelevant to the workings of the legend.

(If you think about it, as you watch A Fistful of Dollars, you recognize that it’s clearly intended to be set in Mexico. This begins a trend I’ll discuss further below, but aside from the uniforms worn by some of the secondary characters, it doesn’t matter overmuch to this particular story.)

By doing this, Leone told his contemporaries that they didn’t need to observe these ostensibly American stories through the lens of American history. For Leone, that meant transforming the genre into a sort of cowboy-shaped fantasy, using historical anchors only where they were useful in achieving certain effects in his heightened reality. For other directors, though, this meant they were free to represent their own European perspective on history and current politics, which they did with a sometimes-literal vengeance. They occasionally used American incidents and figures as touchstones, but everything was filtered through the radical-leftist ideology that dominated Italian film circles. We’ll come back to this topic in a moment, when we look at the filmmakers who followed in Leone’s wake. For now, though, you should understand that if you know the Spaghetti Western only through Leone, who treated the genre as a setting for vaguely free-floating fables, then you’re missing a huge part of its history.

It’s true that Leone did, in his later Westerns, start placing stories in more concrete locations, in the middle of specific events, and he did a fair amount of research into the uniforms and military strategy behind the Civil War setting of The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly. But, again, he was never all that interested in the history the way the traditionalists were, as a way to reflect America back to its audience. Often, Leone’s references were simple homages to his favorite American Westerns and their filmmakers, especially Ford, whom he revered. And even this amount of direct historical awareness set Leone aside from other makers of European westerns.

A Night at the Opera

The second of Leone’s great innovations was in his discovery, or recognition, of a unifying aesthetic for what he saw as a largely mythological story. Naturalism wouldn’t be appropriate; the whole point was to divorce the material from the real world. So, instead, was there an existing creative framework that would be a good point of reference for this new approach to the genre? If you’re a proud Italian in Europe, with a deep interest in storytelling, and you want to transplant this foreign genre into more familiar soil, hoping to emphasize the myths-and-legends feeling it gives you, is there an obvious choice?

Yes, there is:

Opera.

It seems crazy to try to imagine a marriage between the Western film — dusty, wild, and very American — and the European opera, especially the Italian variety, with its stagey spectacle and air of formality; but when you look at Leone’s first couple of movies, it becomes clear that’s exactly what he’s doing, right from the start. It makes sense, too: operas told stories of mythical adventures just as often as they took on the lives of historical royalty or other subjects, so the jump isn’t nearly as nutty as it might seem. Structurally, Leone’s Westerns map closely to the operatic form: you have a scene of quiet exposition, as the recitative; then a buildup to a confrontation, which plays as an aria; then the brief, brutal explosion of violence is the aria’s climax; and then the cycle repeats. The visual storytelling is done cinematically, with the camera and editing, rather than with stagecraft, but the model matches.

Also, look up Puccini’s La Fanciulla del West sometime.

It extends to the characters, too. The American viewer draws a clear distinction between hero and villain, but Leone saw them as much more closely linked, because however much the hero might be motivated to defeat the villain, both of them use violence as their primary tool. For the American audience, this just comes with the territory, but for an outsider, it raises a questioning eyebrow. And opera is replete with stories of questionable heroes, flawed men (mostly) who at first display good intentions, more or less, but who then struggle and sometimes fail due to weakness, or who are led morally astray by bad judgment or personal faults to which they are blind. Maybe they’re hotheaded, maybe they’re too aggressively ambitious, maybe they’re burdened by jealousy (so, so much jealousy in opera). Whatever it is, the central character in many operas will start out as seemingly noble and admirable, but then (as my children say) he Makes Bad Choices. He may still prevail in the end, but he’s not as purely heroic as we assumed.

And if you’re still not convinced, just listen to the score. Leone’s approach to music, working with his frequent collaborator Ennio Morricone, was radical and hugely influential, and it’s the key that unlocks his intentions. The score in A Fistful of Dollars is fairly restrained, but you can feel Leone asking Morricone to start flexing certain muscles; and it’s with their second movie, For a Few Dollars More, that this idea truly flowers. From here on, music is omnipresent, a constant undercurrent even in the quietest scenes, with specific, recognizable leitmotifs accompanying various characters. In some cases, as with the pocketwatch in that second film, the music actually becomes an active participant in the story. And it’s absolutely not accidental that when the movie reaches its emotional and action climaxes, the score invariably puts the human voice in the foreground, with soaring sopranos wailing melodies over the rhythmic chants and barks of baritone choirs. The characters onscreen may not be singing — but the movie is doing the singing for them.

Leone’s style and technique were so revolutionary, and so explosively popular, that his films immediately became the template for the new subcategory of Italian, and later generally European, Westerns. Some of the more artistically minded filmmakers recognized the operatic angle, including “the Morricone feel” of the soundtrack, and replicated it thoughtfully; others just enjoyed and imitated the surface artifice without understanding its source. (Many, many Spaghetti Westerns feature characters who carry a musical pocketwatch.) All of them followed Leone’s lead in highlighting the violence, particularly scenes where villains attack and abuse defenseless, often nameless townspeople and other innocents to establish their detestable bona fides. Some, like Leone, were commenting critically on the pervasive nonchalance of killing in American movies, while others were more indulgent of audience bloodlust, and turned up the brutality for its own entertaining sake. Either way, it was a reaction to the casual violence in the American Western, and as a result these movies became more overtly vicious and bloody than their American inspiration.

In the end, some of these films are aggressively creative, artistically challenging, and still worth watching; many more are formulaic clones, produced en masse because they were cheap, easy to sell, and hugely profitable. Overall, in the end, the result is a category of film that is aesthetically, creatively, and thematically distinct, and we call it, collectively, the “Spaghetti Western.”

The Spaghetti Western

The term arose because these films were at first mostly directed by Italians, and filmed under the banners of Italian production companies. As a broad label, though, it’s something of a misnomer, for several reasons. To begin with, while the initial wave of movies came largely from Italian filmmakers, they rarely used Italian locations for their exteriors, choosing instead to shoot their landscapes mostly in Spain or elsewhere. Further, as the category took off, other directors and production companies got involved, making it no longer an exclusively Italian effort. In addition, the money behind the productions usually came from all over Europe, and sometimes even from the US.

Most importantly, though, the major actors were never predominantly Italian, even in the early years. At first, the tendency was for American actors to be given the leads, with an eye toward US distribution. But producers were surprised to discover a hungry continental market, so the need for an American name on the poster became less important, and casts were pulled from all over Europe.

There was no logistical problem with this, either, as far as the needs of the dialogue. To streamline filming, and make production faster and cheaper, directors would frequently shoot “MOS,” that is, without recording any sound on the set. They would then construct the audio in post, recording all the dialogue in the studio (sometimes with some of the original actors, sometimes few or none), assembling all the sound effects from scratch, and layering in the music. That meant they could produce the film in any language (or several), depending on where they were making deals for distribution.

It also meant they could mix and match their casts freely, hiring marketable (but affordable) names and interesting faces from pretty much anywhere, without regard for their language skills. The actors typically spoke their own native tongue in front of the camera, while the director or an assistant yelled instructions at them during the scene (because, remember, sound didn’t matter). Occasionally, if the production was aimed at a particular market (usually the US, but not always), the international actors would try to speak a broken, phonetically-learned approximation of some specific language in order to vaguely synchronize the mouth movements with the later dubbing, but this wasn’t common.

As a result, it’s not at all unusual in one of these movies to see a scene in which (for example) a character played by a German actor is threatening a character played by an American actor while being held back by a French actor, with a character played by a Spanish actor observing in amusement from the sidelines, all of which is being filmed in a saloon soundstage in Rome. You kind of roll with it as you’re watching, but if you try to imagine the linguistic chaos of the actual shoot, it can make your head hurt.

Incidentally, it’s amusingly ironic that Leone’s approach was so immediately copied by other filmmakers, considering that A Fistful of Dollars was itself a naked duplicate of Akira Kurosawa’s Yojimbo from a few years before. (It’s good, Kurosawa famously said of Leone’s film, but it’s mine. A lawsuit, and a settlement, followed. Unmentioned by Kurosawa was the fact that he himself had lifted the plot of Yojimbo from a Dashiell Hammett novel.)

In any case, it took a couple of years for A Fistful of Dollars to reach the United States. Initially, American distributors were unsure whether there would be a market for this sardonic, stylistically strange, and very violent foreign production. But as the domestic Western continued to decline (one of the high profile offerings of 1966 was a soggy remake of Stagecoach, for crying out loud), and as mounting overseas grosses became impossible to ignore, United Artists finally went to Italy to make a deal. By that time, Leone had already made his followup For a Few Dollars More, and he and his producer were open to yet another movie to round out the trilogy, if the Americans were willing to chip in. They didn’t quite have the story nailed down, but they had the title: The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly. United Artists wrote a check, and the following year, all three of Leone’s movies hit American screens within an eleven-month span.

Reviews were very mixed — most critics were repelled by the violence — but ticket sales were strong. American audiences, clearly, were ready for a new angle on this timeworn genre. And with Leone having proved the financial viability of the Italian Western — and, specifically, once he’d laid down an aesthetic template that clearly connected with audiences — other filmmakers rushed to follow. This was true during the couple of years these movies were successful in Europe, before the Dollars trilogy opened in the US, but after 1967, when the American money started rolling in, the floodgates really opened.

The thing is, though, as I mentioned above, if the Leone movies are the only Italian Westerns you’ve seen, then you don’t have the whole picture. You know from Leone that these movies are violent, cynical, and highly stylized, but if you go beyond Leone, and start really digging into the category, you will discover something surprising: the Spaghetti Western, beyond Leone, is incredibly angry.

When you understand the hard-left politics of the Italian film community, this begins to make sense. These filmmakers were activists, but they were also opportunists: they desperately wanted to get their message out. When Leone showed there was a demand for these European-styled Westerns, meaning that there was entrepreneurial money available to finance them — and, more importantly, when Leone’s work demonstrated that the films didn’t need to cater to American interests, and the makers could talk about whatever they wanted — of course political directors flocked to the genre. Basically, they knew they’d be able to undergird the stories with a powerful left-wing agenda, and there was a good chance audiences would come have a look. Why wouldn’t they embrace the opportunity?

Leone’s Westerns have a sort of weary social cynicism, but other filmmakers infused their work with true outrage, and a sense that social inequity thwarts justice more than a lone black-hat. In the Spaghetti Westerns ostensibly set in America, authority figures usually play a villainous role — not just corrupt lawmen, amoral merchants and business moguls, and predictably slimy politicians, but also the bounty hunters who traditionally had been adjacent to the law, as hunters of the wicked, but quickly evolved into wicked men themselves, greedy and violent. And on the flip side, thieves and bandits, the types who used to be Western villains, now, often, became figures of sympathy, barely able to scrape their undignified survival from society’s neglected edges. The more Spaghetti Westerns you see, the more you realize this is a unifying perspective in the genre, that it’s a pointed criticism of American-style capitalism, and of the moral hypocrisy of the insulated, privileged classes it has elevated.

In addition, Spaghetti Westerns look directly at issues of racial injustice much more frequently than their American forebears. Native American characters are rare, but the Italian Westerns do not shy away from telling stories about black and especially Mexican characters — not always successfully, but with conscious intent that is striking compared to the vacuum in their American inspiration. Be warned: in their portrayals of prejudice and abuse in the period, they do occasionally cross the line from righteous fury into wallowing indulgence. While no Spaghetti Western of which I’m aware gets anywhere near the deranged voyeurism of the loathsome (and also Italian) exploitation milestone Goodbye Uncle Tom, you should exercise some caution in your viewing.

And finally, one deeply fascinating wrinkle in the agenda-driven filmmaking in this genre is the so-called “Zapata Western,” a mutation of the Spaghetti Western which sets its action in Mexico. This was almost unknown in American Westerns, but European filmmakers made a whole lot of them, taking advantage of the revolutionary history of the period to reflect on similar political issues and concerns in their modern world, and making arguments for or against equivalent revolutionary activities in Europe and elsewhere. This is probably the one type of Spaghetti Western where the filmmakers were more likely to do their historical homework, because they wanted their political arguments to be taken seriously.

In the end, alas, as brightly as this strange little corner of the movie world had burned, it wound up flaming out pretty quickly. Only five years after its explosive beginning, it started to falter, with ticket sales lagging and serious filmmakers losing interest. Anxiously chasing audience attention, producers subjected the genre to yet another mutation, leaving behind sober-minded action allegories and embracing a broadly comic burlesque; greasy buffoons marched across aging, sun-bleached Western sets, rattling off dirty jokes and performing strained slapstick for the cheap seats, making fun of the violence and hypermasculine posturing of the earlier movies. It worked for a little while — My Name is Trinity sold quite a lot of tickets in 1970 — but even that was a temporary rescue.

And that was followed by the last, weirdest, and most desperate mutation, wherein Italian filmmakers responded to the rising popularity of martial-arts movies by actually featuring kung fu scenes in their Westerns, often including legitimate kung fu actors imported from Hong Kong. In 1974, for example, the Shaw Brothers came to Italy and co-produced The Stranger and the Gunfighter, teaming their star Lo Lieh (King Boxer, aka Five Fingers of Death) with Lee Van Cleef in a hybrid vengeance-slash-hunting-for-treasure story. It’s not very good, but it’s occasionally entertaining in its sheer weirdness.

But within a handful of years, the category was completely dead, supplanted by sex comedies and the newly trendy poliziotteschi, or Italian crime film.

In the years it lasted, though, the Spaghetti Western was hugely influential, and gave us a number of movies worth discussing as classics of not just the European subgenre but of the Western in general. Following are several films, and filmmakers, you should know about.

Sergio Leone

The most important director, obviously, as discussed above, is Sergio Leone. He didn’t make very many Westerns — after his early successes, he had to be dragged back for the last couple — but most of them are, at the very least, worth seeing. In contrast with his peers, he remained defiantly the artistic filmmaker, less concerned with political agendas and more interested in pure cinematic effects: meticulous and highly expressive cinematography, experimental editing, and other directorial flourishes. His “Dollars Trilogy” is, of course, essential, with its final film, The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly, regarded by many as one of the crowning achievements in Westerns, if not in cinema history. His Once Upon a Time in the West is also terrific, if perhaps a bit overlong. All of these are must-sees.

Leone’s later movies are worth watching for the serious fan, but they’re best understood as “inside baseball” for the aficionado. In particular, Leone’s last Western, 1973’s My Name is Nobody (technically credited to Tonino Valerii, but with Leone watching very closely over his shoulder the whole time), seems like an oddly comic departure for the filmmaker, and an unusual swan song that doesn’t fit with his earlier material. But if you know the evolution of the genre, and its later drift into broad spoof, you can feel Leone’s satirical intent, and his grumbling about the state of the Italian Western. The point is, if you find yourself hooked by these movies and watch a lot of them, you’ll probably enjoy Leone’s last couple of entries as artistic commentary; but for the casual fan, they’re not really essential.

Now, here, as we move beyond Leone, you should bear in mind what I said at the top, that when it comes to the Spaghetti Western, there is Leone, and there’s everybody else. Again, it’s not that Leone’s movies are better than the rest. Rather, Leone stands apart because, for him, the filmmaking craft was the priority, and the politics, if any, were secondary. He was a notorious perfectionist on the set, driving artists and technical crew crazy with his precise demands for framing, camera movement, timing, performance, and more. By contrast, the other directors working in this space were, by and large, satisfied with “close enough.” There are certainly moments of thrilling inspiration, even extended sequences, where the choices are brilliant and the execution is spot-on. But you will also see shots and scenes where it’s clear they were content just to get in the ballpark of the plan — notwithstanding a clumsy camera move, a slapdash lighting scheme, or whatever — and then move on. They were not after Leone’s level of refinement: as long as the themes and political agenda were clear, they were satisfied. So as you get into these movies, you should be prepared to look past the sometimes unpolished surface to see what the directors were actually going for.

Sergio Corbucci

And that brings us to Sergio Corbucci, who is, after Leone, certainly the most significant director in this category. He’s much less well known among English-speaking audiences, which is unfortunate, because he’s got a couple of towering classics in the genre. Part of the problem is the bleakness of his work; while other political filmmakers in the genre were angry, Corbucci is downright furious, telling stories so blisteringly raw that they’re still hard to watch. On top of that, he was insanely prolific during this period, making ten movies in five years, leading to quality control problems and uneven output. He’s kind of like the Takashi Miike of Spaghetti Westerns: he churns out a lot of work, and while not everything is distinguished, even the worst movies have a scene or a character or even just a single shot worth celebrating. (It’s not a coincidence that one of Miike’s movies is a pretty direct homage to Corbucci.)

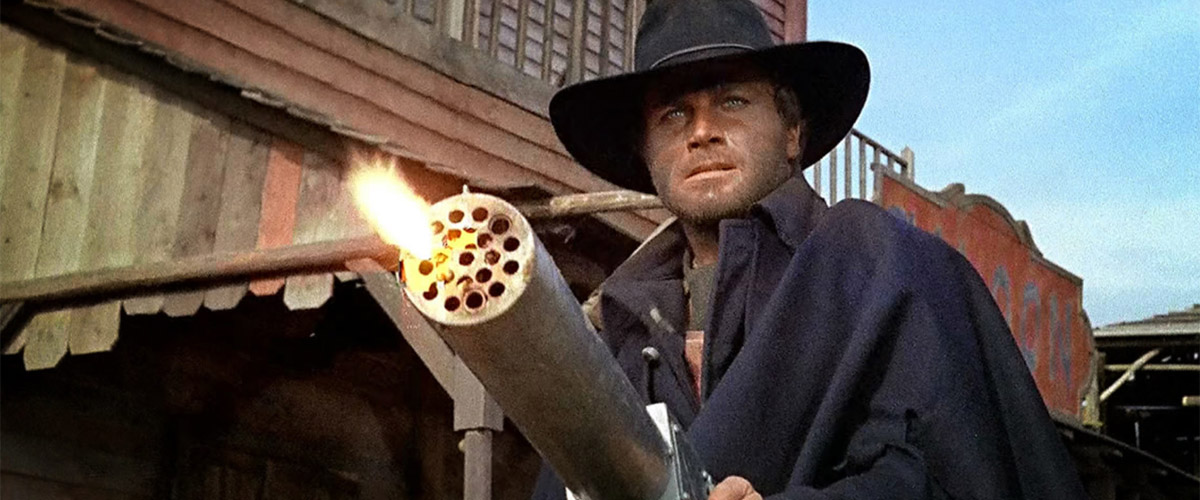

And, like Miike, Corbucci occasionally puts it all together, and gives us greatness from beginning to end. His most famous film, and biggest hit, is Django (1966), which made a star of Franco Nero and spawned dozens of imitators and ripoffs pretending to be Django sequels. The story is a straight clone of Leone’s Fistful of Dollars, with the central character playing two gangs of lowlifes against one another, but it has a grim viciousness that sets it apart. It’s also more interested in symbolic meaning than Leone’s movie; while Eastwood’s Man With No Name wears a costume that is iconic in its simplicity, Nero’s Django wears a hodgepodge of items intended to reflect his low status and working-class character.

Even better is The Great Silence (1968), probably Corbucci’s masterpiece, and a movie that still has the power to enrage and jolt. If you’ve seen Tarantino’s Hateful Eight, you’ll be amazed to find that many of its best ideas are straight stolen from Great Silence, from the unusual snowy setting to the way the stagecoach is used as a first-act setup device. It’s about a bounty hunter, mute since a childhood injury, seeking vengeance against a bloodthirsty gang of competing killers who have cozied up to a pushover lawman to take control of a small mountain town. Like all of Corbucci’s films, the production is sometimes crude; you can tell he’s making his movies at a dead sprint with almost no money. But with its wintry landscapes and characters trapped in hopeless despair, it builds an atmosphere of mounting anguish that is finally released in a genuinely upsetting finale. It’s not shock for shock’s sake, either: Corbucci is saying something really specific, and he’s using a sledgehammer to your forehead to deliver the message. If you see only one Corbucci, make it this one.

As far as Corbucci’s other films, after Django and Great Silence they start to fall off quality-wise. There are three on the next tier that merit a look, though. First is Navajo Joe (1966), a bog-standard revenge story — man hunts his family’s killers — except for the unique twist that the hero is Native American, and the murderers are Americans. If you can ignore the utterly bizarre casting of Burt Reynolds in the lead, topped with a ridiculous wig, there’s a lot to enjoy here, good action and solid catharsis and clear political intent. Then there’s The Mercenary (1968) and Compañeros (1970), the director’s two entries in the “Zapata” genre, which are both energetic and entertaining, but additionally interesting because they feel like Corbucci taking two cracks at the same basic material. It’s not quite a first draft and a remake, but they’re definitely close cousins.

After these movies, Corbucci’s output is increasingly spotty, sloppy, and repetitive, but could be worth sitting through if you enjoy hunting for his rare flashes of brilliance.

Sollima, Castellari, Petroni, and Damiani

The next director with a noteworthy filmography is Sergio Sollima. He made only three Westerns, but they range from good to excellent, and show a degree of care and craftsmanship greater than usual in this genre outside of Leone. The first, The Big Gundown (1966), is probably the best, with an unusual setup, rich characters, and a genuinely surprising plot turn that gives the film real thematic resonance. The second, Face to Face (1967), is also very good, but it’s more nakedly allegorical, verging on Brechtian in the transparency of its metaphorical argument. On the one hand, this directness gives it the power of agitprop, but the characters are obligated to follow the demands of the allegory and thus feel less like people and more like pieces on the director’s chessboard. The third, Run, Man, Run (1968), is a direct sequel to the first film, and is probably the least of the three; it repeats many of the same arguments and ideas from the previous two movies, and grafts them onto a plot heavily inspired by the chasing-the-gold business from The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly. Still, Sollima directs with a sure hand, so it’s a reasonably easy sit.

Another filmmaker to look at is Enzo Castellari. He was extraordinarily prolific, across multiple genres, and is best-known these days for The Inglorious Bastards (1977), the war movie whose title Tarantino borrowed and mangled. During the heyday of the Spaghetti Western, Castellari made a number of them; some are disposably formulaic (Any Gun Can Play, 1967, is yet another searching-for-hidden-gold story), but he had a nose for material outside the usual. Kill Them All and Come Back Alone (1968), for example, is an oddball heist movie, kind of like an Old West Oceans Eleven where the team members are constantly double-crossing each other. Johnny Hamlet (also 1968) is even stranger, transplanting Shakespeare’s moody revenge classic into a Spaghetti Western setting, which works a lot better than you’d expect. Then, in 1976, after having moved mostly to modern crime stories, Castellari came back and made Keoma, starring Franco Nero, as a Bergmanesque eulogy for the dead genre. The plot is derivative and uninteresting, but this isn’t a movie about plot; it’s slow, somber, and funereal, filled with eye-popping yet bleak compositions. The opening shot alone is a clear announcement that you’re in for something different.

Death Rides a Horse (1967), directed by Giulio Petroni, is a clever tweak on the typical revenge plot, featuring two men separately seeking vengeance against the same group of bandits, and alternately interfering with and aiding one another along the way. The violence is vicious even by Spaghetti Western standards, so be warned. On the positive side, star Lee Van Cleef is in top form; his performance here measures up to his work for Leone. From the same director, A Sky Full of Stars for a Roof (1968) is pretty good, and notable as an early example of weaving humor into the formula. It’s also got a killer opening sequence. Petroni’s Tepepa (1969) is uneven, and mostly notable for featuring Orson Welles as the villain. To say he phones it in would be generous; he’s clearly irritated at having to slum in what he no doubt considers an inferior genre, possibly in order to fund the editing of Don Quixote or one of his many other half-completed projects.

A Bullet for the General (1967) is the first significant entry, and possibly overall the best, in the “Zapata Western” subcycle. Elaborately plotted, and serious minded about its setting in the Mexican Revolution, this film by Damiano Damiani established several elements that would be copied by subsequent imitators — corrupt and/or weak-willed civic and military figures, a leading duo who are challenged in their revolutionary sympathies, and a general cynical sense that however attractive revolution may be in the abstract, it’s messy and difficult in actual practice. The film is always interesting, even when the action is paused to allow extended narrative housekeeping.

There are many more good Spaghetti Westerns out there, and this article could continue for another dozen or so paragraphs. That’s not because the Spaghetti Western is generally underrated; every category of film has its share of junk, and the Spaghetti Western is no different. Rather, it’s simply that the category is surprisingly large. By most measures, over five hundred Westerns were made by Italian producers between 1962 and 1975, and at its peak, in 1968, fully a third of the Italian film industry’s output was dedicated to the genre. Much of it, of course, was formula dreck, but with the sheer volume they achieved, it’s natural that some examples would rise to the top.

And it’s not just deep, but it’s broad, too. There were so many movies being made, and such desperate hunger for material to film, that all kinds of crazy ideas got thrown in front of the camera. Want highbrow literary adaptation? Spaghetti Westerns have you covered. In addition to Johnny Hamlet mentioned above, there’s also Dust in the Sun (1972) as another cowboy take on the Prince of Denmark, not to mention The Forgotten Pistolero (1969), which is a reworking of the Orestes story from Greek tragedy, of all things. Or do you want something surreal, psychotronic, and borderline offensive? No problem. Check out Blindman (1971), a bizarre rip on the Zatoichi concept, or Django Kill (1967), a completely unhinged movie that starts with the hero crawling out of his grave and then throws itself headfirst into madness, featuring everything from a squad of obnoxiously-stereotypical gay cowboy villains to an alcoholic parrot.

If you can’t tell, this can be an intimidating, mind-boggling corner of the cinema world. Hopefully the above gives you some context to understand what you’re looking at, and somewhere to get started.

You can see if the movies discussed above are available for rental, purchase, or streaming in your region by checking JustWatch.

Next up: Hollywood fully embraces Revisionism.