Bioware’s Knights of the Old Republic was one of my favourite games as a child, and one specific part has stuck with me in all the years since. No, not the famous twist, nor HK-47’s love of murder or even force lightning-ing everyone to death like the Emperor while cackling madly before my TV, but the thirty second run across a featureless desert I had to make every time I left the town on Tatooine.

This commute stuck with me because for the first time I felt like I was in a vast, endless world like the one the game told me I was in. There was a spaceship battle or grand, CGI cutscene every half hour but only there in the desert did the scale of it all feel real and tangible.

And Bioware would capitalise on this feeling in their best game.

Mass Effect is the only game I’ve ever played to truly make me feel like I was in a huge, open universe. The myriad worlds I visited on my quest to foil Space Cthulhu felt truly huge and boundless, and most importantly like an actual existing world instead of an endless series of levels. This was accomplished through a mixture of large-scale level design and fluid gameplay.

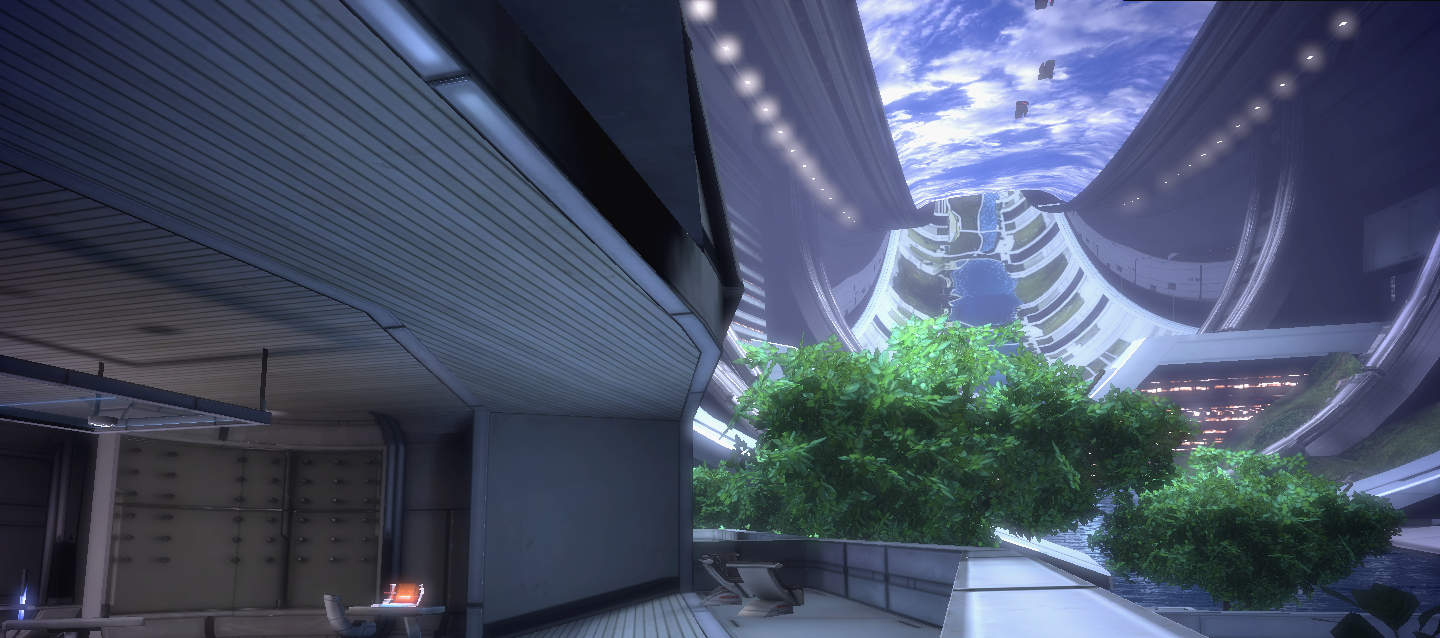

Scale is the main element of ME’s level design. Everything feels huge, from the safe zones to the action zones and even minor sidequests are built on a grand scale. Barely an hour in the player is given free reign of the Citadel, an enormous space station setting the stage for the rest of the game’s world. The playable areas feel genuinely large, from the galactic council chamber to the wards and especially the huge, garden-like estates linking all the major areas.

online pharmacy purchase temovate online best drugstore for you

A good part of this is that the game is willing to let large areas go by without anything obvious for players to interact with. The amount of free space lets the world feel like a real place that’s designed for its own purposes and exists for its own sake, and continues in its existence when the player is not there, as opposed to a level created solely for the player’s experience.

online pharmacy purchase lipitor online best drugstore for you

The place is populated with enough NPCs and minor player interactions to feel lived-in, but having to spend time moving from place to place and taking in the scenery does wonders for selling the illusion of the world. This illusion extends outside the playable areas too, once you buy the area you’re in as a real place then similar-looking ones glimpsed in the distance are imbued with that same sense of reality and life, and once you do that the world truly becomes a world.

The other main way ME’s level design sold its world’s scale was the Mako (which really wasn’t that hard to drive), the player’s APC which let them traverse planets across the galaxy and fight anything larger than a moderately-sized killer robot. This let the game put the player in massive environments to explore or fight their way through, including entirely optional side-planets the player could drive around for ages, but what really conveyed a sense of the world’s size was the fluidity between driving and on-foot gameplay. The player can leave the Mako and wander about on foot at any time, and in many missions are forced to, and the transition is utterly seamless. All depictions of scale in media work by contrast and the difference between the two here is what really sells the enormity of the galaxy.

Had Bioware separated them with loading screens the effect would be lost as they would feel like separate entities, but the seamlessness keeps the world feeling continuous. Loading screens remove the player from the world for a second, which can be useful in dividing up locations and time or conveying a sense of distance (ME uses them well when travelling across the galaxy), but they are detrimental when multiple areas need to feel like parts of the same place. This approach extends to the game’s hidden loading screens, concealed as lifts or the Normandy airlock’s decontamination procedure. As well as keeping the player within the world these brief delays feel like an actual movement between places (even if the hard-coded lift times are ridiculous), or an actual procedure the crew of a starship needs to follow.

It’s little things like this that go a long way to making the world feel like it exists outside the mere needs of the player.

Action zones are also not designed to comfortably fit the game’s style of combat. This may sound like a terrible design choice but I mean that each area, while containing cover points and explosive barrels to be shot, does not feel tailored for the gunfight taking place within it as if that was its only function in existing. Most feel like normal buildings built for their own purpose that just happen to have become warzones. There’s an immersive awkwardness to the level design and combat which feels like fighting in a place not designed for life-or-death struggles, and the combat feels very much like an extension of character movement in non-combat environments, making the two feel like part of the same experience. Combat also takes places at long ranges for the genre, helping to sell the feeling of a genuine firefight as opposed to a crafted, Gears of War-style action setpiece existing solely for its own sake and not to progress the story in any way.

Nothing shows just how well Bioware pulled all this off in Mass Effect 1 as just how badly they screwed it up in the sequel. The world of Mass Effect 2 is a series of corridors, tiny rooms linked together solely to house everything the player can interact with in the smallest space possible. There’s no room for the populations of the worlds to live in, and without that feeling of life to make the world feel convincing the skyboxes just seem like painted backdrops instead of an extensive world. Even Illium, one of the richest planets in the galaxy, feels more cramped than the dystopian world of Blade Runner:

The replacement of hidden loading screens with traditional ones also cuts up the environments, removing the feeling of a large, continuous world, and the loss of the Mako and lack of a replacement1 removes the feeling of a wider, open universe which gave the first game much of its fantastic atmosphere.

The style of action gameplay is also radically different, redesigned to a very generic, cover-based shooter style, which jars drastically with the non-combat portions of the game. There’s now a very noticeable divide between the safe and action zones in the world; gunfights can now be predicted because of the sudden preponderance of ubiquitous chest-high walls for no other reason than because a shootout is about to take place. The smoothness of the gunplay also feels very different from movement outside of gunfights, and every attack, biotic power and movement is quantified so there is no feeling of naturally evolving firefights. Every time an action beat starts you are violently reminded you are playing a game.

The most important thing when designing a narratively-driven game is that the gameplay should serve the needs of the story and world and be tailored as much as possible to support that, instead of the other way around. Mass Effect 1 was a mechanically flawed game, but many of its flawed elements leant themselves well to creating the feeling of a wide, open world that immersed the player, whereas its sequels tried to fit their stories over a pre-existing mechanical framework often at odds with the story they wished to tell and suffered for it.

Footnotes:

1I’m not counting that terrible DLC hovercraft thing.