Cliff Martinez has found his way to the common tongue in film and game circles thanks to his emotionally frank and transparently gorgeous work for Steven Soderbergh and, lately, Nicholas Winding Refn. His perhaps best-known piece, even if its source is little seen, is his stunning rainbow of pain and hope for Soderbergh’s Solaris. You hear this masterpiece in advertising, in film trailers, in countless other composers’ work desperate to flatter with lesser imitations. I wish that strange, quiet film were better known. I’m going to talk a bit about the unity of film and music, which of course is the mission of any score – and none other achieves this with the evocative wallop of Solaris.

Synesthesia

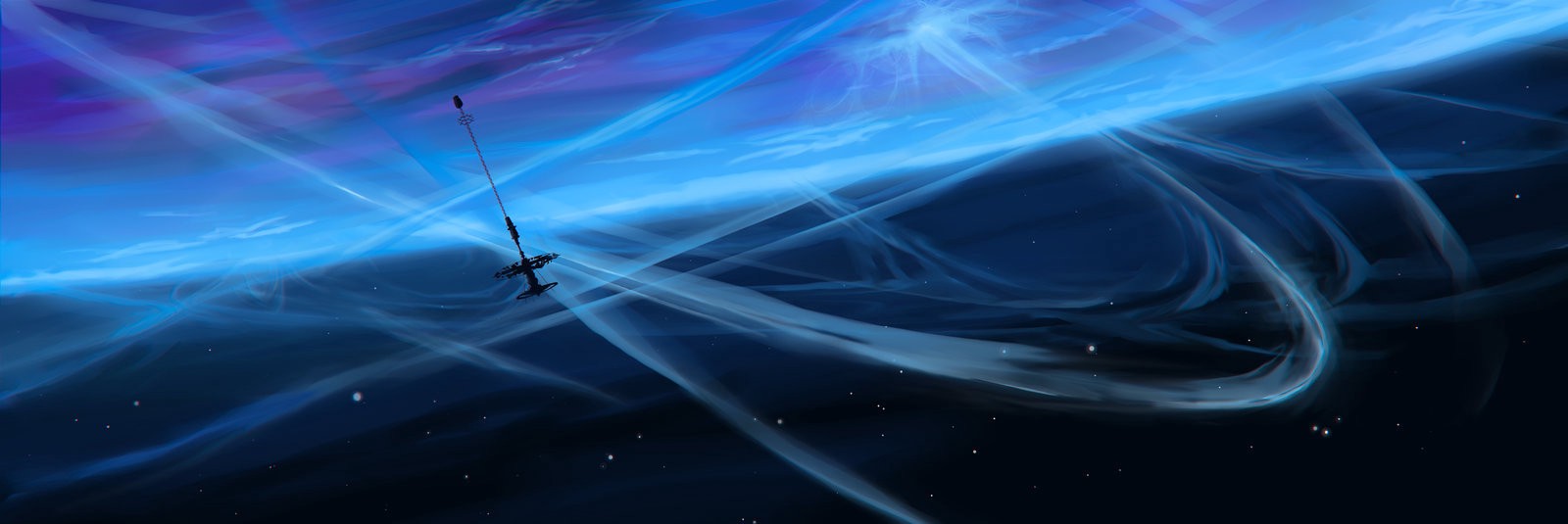

The film, ostensibly science fiction, is about a great incomprehensible storm that blankets a distant planet and that, somehow, is a nexus of all galactic consciousness.

Visualize turbulence. Clouds overlap each other, sometimes they part and the sun shines through. They collide and disembowel each other, and the rain comes. Its color is decadent. Blues and purples clash and release reds and greens. Everything moves.

Now imagine this as a music. What is it? How do you render the ambivalent tides of an atmosphere as familiar sounds? This is how. “Death Shall Have No Dominion.” Immense chords, each holding long, stubborn strains. One infects another and the result is cacophonous and transcendent.

Listen.

The music swells and decays in great billows. There is no melody in these swarms. There is awe, There is harmony which, in this piece, is melody without bones. There is sadness that resolves to hope.

Life and death refuse to separate. There is so much potential here, but no story.

Memory

Martinez allows a hint of dance-hall convention to ground some passages – specifically, and meaningfully, when the film dips into memory. The retelling of Kelvin’s relationship telegraphs years of love and pain, all set back on earth in familiar locations. Parties, homes, the social settings we inhabit every day.

A slow sequenced bass line cuffs these sequences to nostalgia.

“Don’t Blow It.” This piece makes me cry.

Consider memory. Feelings follow images or sounds or smells, and then we tell ourselves stories. Stories have structure, they have bones and melodies and, most importantly, rhythms. You can dance to stories.

Mystery and Familiarity

The iconic pulsing tines of Martinez’ customized metal instruments – steel drums and his famous cristal baschet – are a constant emotional tour-guide through the unknowable. As the symphony swells and releases chaos and terror, his friendly staccato rhythms reassure us. When they disappear and all that’s left are the great alien clouds, we are vulnerable. The stories, metaphors for what’s knowable of our universe, have left us.

Each of these instruments – the symphony, the bass, the metal rhythm – are characters. The score is allegorical, as many film scores are – but it is less dependent on conventional melodic themes. The score, as the film, allows alien, memory, and present to collide. Past and present are united, and the score launches into catharsis – the unhinged strains of the extra-terrestrial present join with the anxious pulse of memory.

“We Don’t Have to Think Like That Anymore.”

Persistence

So why does this score, more than his simpler, more structured work, persist? Why do we still hear it? Because it evokes awe, and awe reassures us that everything is knowable and beautiful. This is arguably music’s final goal.