If you say something doesn’t have any cultural impact, yet you’ve spent the last 10 years constantly and emphatically asserting this claim, are you sure there that what you claim is actually the case?

Ever since the record-breaking box office success of the Sci-Fi adventure Avatar in 2009, James Cameron has been threatening us with a series of sequels. However, the upped ante of each consecutive announcement has been met with a mix of bewilderment, ridicule, and otherwise abject disinterest. A curious position for a film/intellectual property that held the title of the highest grossing movie in the world for many years, bested only by the might of Disney/Marvel’s Avengers: Endgame a decade later.

To be sure, there’s plenty to criticize about the film: its highly derivative narrative structure and its offensive use of white savior-ism tropes are the two most common complaints, although its inherent strangeness is also a significant factor. After all, a movie with 9 foot tall cat people is fucking weird no matter how you slice it. Recognizing this, this article is neither an obituary or an autopsy, as I will leave it to other more learned scholars to dissect how and why the original film was so successful. Instead, I am taking past experiences and our present circumstances into account to postulate how the Avatar series may still be quite relevant to modern popular culture, despite the perception of its obsolescence.

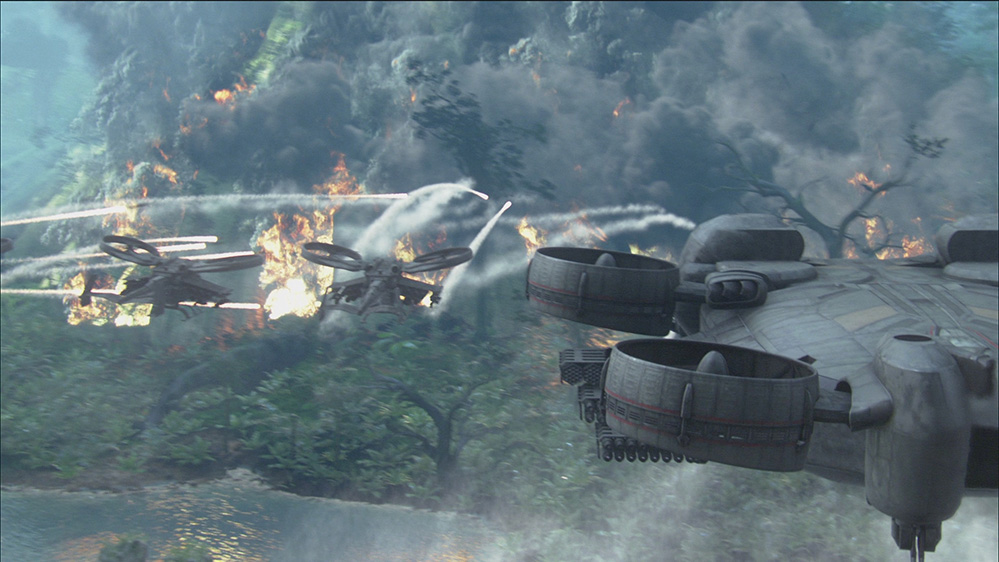

The MCU films of the past several years have touched upon the military industrial complex, drone warfare, and even elements of colonialism. For my part, I found that despite the intriguing premises, most of the films shy away from or fall flat of any incisive criticism. Film Journalist Siddhant Adhlakha has an excellent series examining the entirety of the MCU thus far, in which he takes the analysis a step further and postulates how the series may in fact promote the very things it purports to condemn. Avatar tackled those issues overtly, though not without critical errors of its own. Even so, I am curious to see further exploration of those themes in a different context. The parallels/allegory between the fictional Na’vi race and real-world indigenous people has been well documented. Likewise, the plot of the film echoing other movies such as Dances with Wolves, Pocahontas, and even Fern Gully is the punchline of many an internet meme. I always found this curious because the most obvious and critical difference between Avatar and those other stories is that the colonizers (white people) lose at the end. This is theoretically perhaps one reason why the film seemed to resonate with audiences around the world during its theatrical run. Logically, however, it stands to reason that while the indigenous people win the battle, the war is likely far from over. After suffering great calamity, the threat of retaliation leaves an even greater sense of impending doom.

To that I say simply, bring it on. What we have thus far is, at least on paper, fertile grounds for a sprawling modern science fiction saga. I feel this is a particularly promising prospect after a disappointing and, frankly, pointless resurrection of the Star Wars franchise and a buffet of superhero films that only occasionally rise above forgettable entertainment. Of course, Avatar certainly isn’t Shakespeare and Cameron isn’t known for being a screenplay virtuoso. Still, I’m genuinely curious about what he has to offer, whereas with the other big-name ventures based on already existing properties, I already have an Idea of what to expect.

But what of the problematic character conceit at the center of this series? How can it possibly still garner support after all we’ve been learning about the effects of institutional racism in media and the pursuit of greater multicultural representation? In Avatar, a white man inserts himself into an indigenous culture, becoming a vaunted warrior chieftain who performs deeply symbolic feats seemingly beyond the abilities of the very peoples who adopted him. One could interpret the actions of the main character giving up his whiteness as a gesture of solidarity and ally-ship, but even that generous reading has uncomfortable implications. If I had a few hours and a few drinks in me, I could probably conjure up a screed against Jake Sully’s cultural appropriation framed around his obtainment of “ethnic hair”, but I think I’ll save that for another time. Suffice to say, we don’t yet know how much this central issue of cultural identity will be addressed in the sequels, or if it will even be addressed at all. Despite this uncertainty, I am once again highly curious as to how the character of Jake Sully might be explored. If nothing else, there are some real-world parallels here as well that might be used as a way forward.

One of the most fascinating and tragic stories about the American soldier’s experience during the Global War on Terror is the rise and fall of Special Forces Major Jim Gant. He was (in)famously referred to as the “Lawrence of Afghanistan”, deeply embedding himself and several soldiers within a Pashtun tribal area in Kunar Province, Afghanistan. Gant had completely subsumed the code of Pashtunwali into his own battle hardened and wildly controversial operating methods. He had achieved great success in developing the core concepts of Village Stability Operations, using the power of the various host nation tribes as a key force against extremist insurgency. However, he was also haunted by his own demons, ravaged by untreated PTSD and the heavy doses of alcohol and prescription drugs he used to self-medicate. In the end, the superiors that once praised him orchestrated his discharge under disgrace.

The concept of a white savior in and of itself need not be off limits as a story device if one takes the time to explore the many facets of the concept. Again, there is little indication thus far that the sequels may be leaning in this direction, but just as the allegory of colonialism and military domination runs heavily through the Avatar, there is a wide breadth of material to supplement these themes in these potential sequels.

One of the most serious issues facing our planet is the destruction caused by climate change. The damage caused by hurricanes, tsunamis and rampant wild fires is only one part of the equation, as we consider the second and third order effects of agriculture disruption, economic instability, displaced peoples, and even the armed conflict spurred on by the confluence of those factors. Avatar was very clear in its message of environmentalism, one that we have taken for granted. Speaking of conflict, we are once again in the midst of an international incident that could very easily spiral downward into a full-blown crisis of war between sovereign nations. Two adversarial powers vie for control of a region, with millions of innocent lives caught in the middle. In regard to the American involvement, we are already stretched far too thin and so very beleaguered after nearly seventeen years at war. The bellicose bellowing of buffoons signals the march to war in the name of profit and political grandstanding. Blood is shed supposedly in the name of security and liberty, but we all know the real bottom line. A film about an overwhelming military power rushing into a retaliatory crusade under the pretense of defense while precious natural resources remain the true underlying factor sounds like an extremely relevant topic ripe for exploration.

These are but waypoints and roadmaps of how Avatar could remain relevant in the coming years and imminent sequels. But even if none of what I propose comes to fruition, does that emphatically prove the irrelevance of the property? I do not believe that is the case. To dip a toe into metaphysics for a bit, are not the constant declarations asserting its irrelevancy themselves evidence of sustained cultural significance? There are articles about Avatar in some movie news websites that have literally hundreds of posts in their comments sections that are variations of “I don’t care”, but that presents a curious paradox of time and energy spent “not caring”. I would posit that this questioning and denial of the relevancy of this film is what in turn solidifies it. In other words: the concept of a record-breaking blockbuster not having a cultural impact is the cultural impact. Avatar presents us with a curio of mass media and pop culture in the 21st century, a phenomenon that will likely never be replicated ever again, even as the very creator of the phenomenon attempts to rekindle interest with a series of sequels. A byproduct of technological wonder, globalization, and a rapidly changing industry, the lightning in the bottle that is Avatar yields a strange case that continues to be pondered about years after its occurrence, perplexingly in the active dismissal of its own examination. That alone is a cultural impact the likes of which few pieces of media could ever hope to ascribe to. And if it ends up gaining even more impact as time goes on then all the better, deny it as we might.