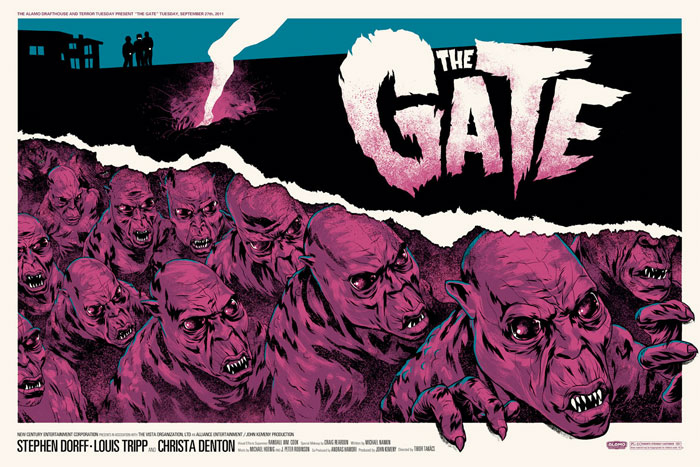

In this series, Adrian and Tanner take us 30 years back in horror film history, to some of our favorite 1987 creepfests.

I was fourteen when The Gate landed and, by the time I was aware of its home video existence, I’d become an asshole high schooler who only watched vicious slasher films and what I thought were art films because they were made before the present decade. By the time I got over this, the film and its sequel were on DVD and I fell for it. Hard. I know that this lovingly crafted charmer is a favorite with fans of 1980s monster business, but it never entered the part of my brain where nostalgia smears vaseline on the lens. There is no reason to review The Gate: either you know it and love it , or you don’t know it but when you do you will love it. The monsters and the effects and the kids and the art design are pretty much perfect. More than any other single film, this is where it’s easiest to see the seeds of modern nostalgic horror like Stranger Things and It Follows. It’s all here.

Here’s the premise: kids fighting off demons who crawl out of a hole in their backyard. Monsters happen. It’s Hellraiser, basically, but less sexy. Wee Stephen Dorff plays Glen, a scrappy pre-teen whose house is infested with an escalating parade of hell seed. He and his pals (and his big shaggy dope of a dog, Angus) fight back, overcoming his big sister’s teenagerly skepticism, a zombie, a big ass satan monster, and the most adorable demons in film history.

WHO’S A GOOD WIDDLE DEMON

Any fan of this film will remember the teensy demon foot-soldiers that scuttle around biting people in advance of the arrival of the film’s winged devil beast. The little guys are an amazing mix of techniques: dudes in suits against blue screens, animatronic puppets, and a bit of stop motion to help them out when they’ve exploded into balls of playdough. The minions (the internet and director’s commentary tell me to call them minions) actually made me a little blue. They’re precious babies, just doing what instinct and Satan Daddy make them do. It’s not their fault they’re compelled to march to their deaths at the hands of horrible pink human children. There is a fan fiction in me somewhere that follows a family of minions as they send their twenty-three children to fight the War of the Hole.

online pharmacy purchase orlistat online best drugstore for you

The aforementioned boss-dad is a big stop motion puppet that looks like an anteater-cum-fish. It’s ridiculous, a little terrible, but also entirely tactile and convincing in its own way.

Satan Daddy

There is even a seriously convincing random zombie guy with gnarly visible jawbones. I’m as sick as anyone of the mostly asinine practical v.

CGI argument, but this film both restarts and concludes it: computers can suck it. This is as convincing an argument for in-camera effects as I’ve ever seen.

If your film doesn’t have backwards heavy metal, it sucks

The kids are awesome. Stephen Dorff is a brave little toaster, never precious or precocious (the two qualities that sink child characters) and his best buddy Terry (Louis Tripp) is a dork who wears Masters of the Universe t-shirts and a denim jacket with Killer Dwarfs emblazoned on it.

Terry discovers what’s happening in Glen’s yard by PLAYING A HEAVY METAL LP BACKWARDS. Yes. This movie has everything. Does Stranger Things have backwards heavy metal records? DOES IT? Stranger Things is garbage.

I fixated on Angus, the family dog. I thought about writing a new treatment from the dog’s point-of-view which is the second time I’ve mentioned creating fan fiction for this film because I love it. Angus is a big sweet doofus and I was prepared to chuck the blu-ray into the eponymous maw when I worried early on that the film wouldn’t give him a proper ending. I won’t say what happens because spoiler, I guess, but I still love the film, so take that as you will.

online pharmacy purchase azithromycin online best drugstore for you

1

Also:

Grody

The 1980s were a difficult time for hair.

1987 was during a strange era for film; digital effects and production workflows were just beginning to make a permanent dent in decades-old lifecycles, even as practical effects development was peaking.

The 1980s of course brought us many landmarks in high-goop filmmaking, but by 1987 Young Sherlock Holmes had come and gone and we knew that digital filmmaking would soon overtake practical effects. This era is a bit like a honeymoon with a dying spouse, at least in hindsight. It’s both a sad and exhilarating time and we will look at many more examples.