(Author’s note: Please excuse the American language in this piece. It feels improper to let it go unsaid.)

When did Peak TV start? What was the actual turning point, when the explosion of quality programming turned into a saturation, that’s still having a deep effect on the day-to-day of popular culture? Did it start with the millennium, and shows like The Wire and The Sopranos? Did the phenomenon grow until January 2007, when Netflix began the first-ever streaming service, or 2013, when it began original programming?

If you ask me, the real bellwether was Sherlock, the first episodes of which aired in the summer of 2010 (in the UK, of course, with a few months’ wait for everyone else, as with the earliest Harry Potter books). The BBC is notorious abroad for its six-to-eight-episodes-a-season standard, but even in comparison the show was positively brief: Three episodes at a time, never less than a year’s wait between releases, thanks to the busy schedule the show’s success gave everyone involved with it.

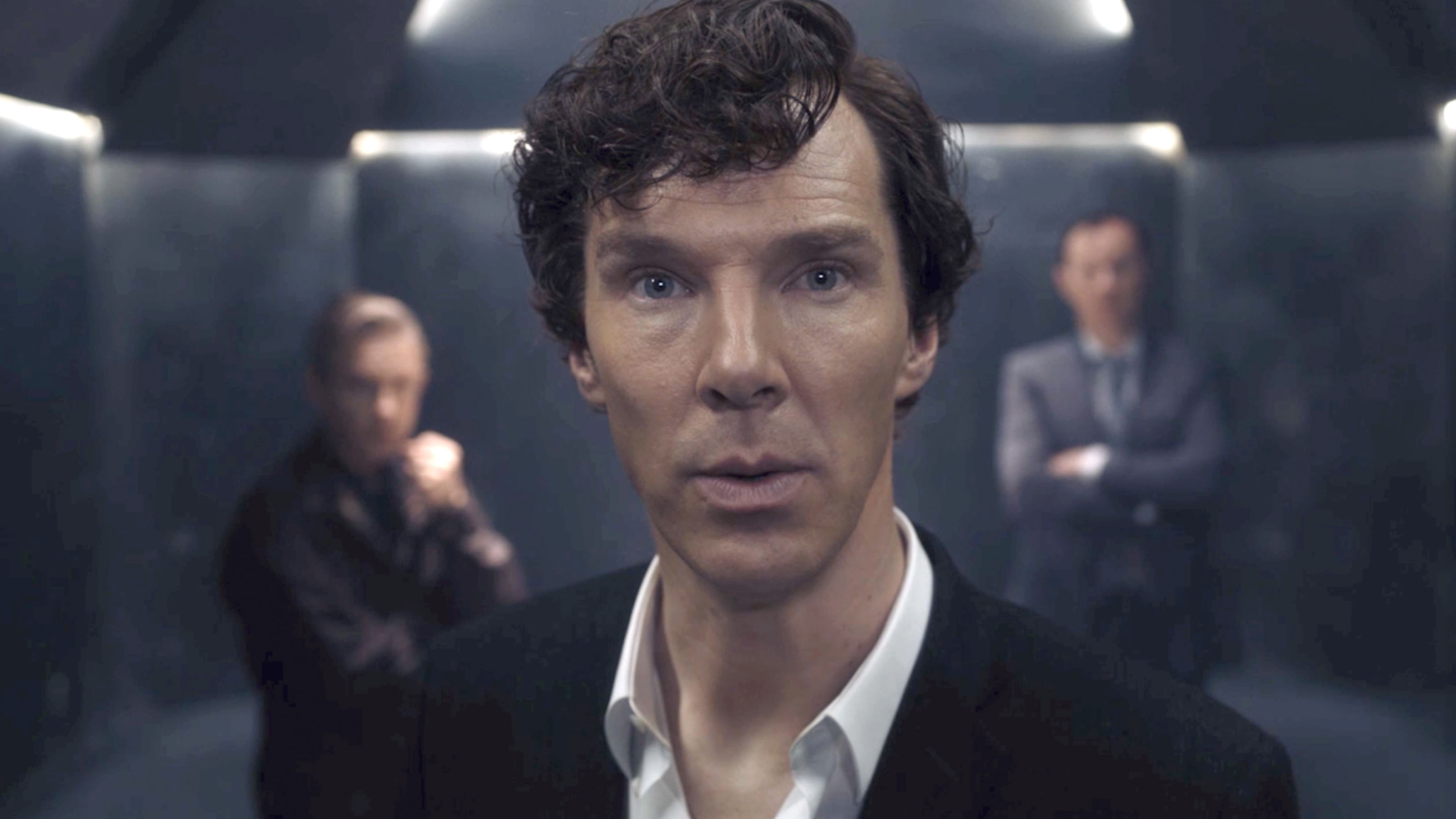

With its coming just months after Iron Man 2 presaged the coming era of television-style filmmaking Sherlock – movie-style television – was in the right place at the right time. More importantly, they had the right team for the job: Actor and comedian Mark Gatiss brought his classicist’s sensibilities and command of psychological mystery narratives (not to mention a commanding and fascinating Mycroft Holmes), TV and genre veteran Steven Moffat supplied his character focus and deft hand with modernizing classics, director Paul McGuigan created a playfully serious modern-day world, and Benedict Cumberbatch and Martin Freeman brought it all together, turning from hard-working but unremarked TV actors into instant stars.

Sherlock became a cross-cultural phenomenon – across oceans, across ages, from fans of Doyle to those of Doctor Who. Every aspect of the production was heaped with praise, but in hindsight, the most pivotal part of the entire enterprise was the construction of the mysteries themselves. Holmes and Watson’s adventures – as Doyle insisted on calling them – were propulsive yet efficient, compelling, plausible, and so very, very clever, confounding even to well-read fans.

As the show went on, and Moffat and Gatiss became more confident and possessive of the material, the mysteries lost their pride of place. More of the writer’s personal touches began to seep in, like Moffat’s textualization of the show’s fan community and the rich history it was drawing from, culminating in a feature-length special last year, honouring the original Victorian setting (note the ‘u’) or Gatiss’ fascination with theater of the mind (that Victorian setting turned out to be an elaborate mental exercise by the modern-day Sherlock, picturing himself and his friends solving crimes in the past, in order to do…not much, honestly).

Elements like these work well as supplements, as stylistic flourishes, but when they become central to the story they can have the unfortunate effect of losing the audience’s investment in the stakes, or being manipulative to the point of losing their trust completely. Why should we care about anything that’s going on if it’s all just meant to be a joke at the expense of us, the viewers, and then maybe turn out to not be real at all, to fake us out?

While I can’t speak for all viewers, I started having that problem with the very first scene of this season’s first episode. After three long years of cliff-hanging, the apparent return of the long-deceased Moriarty gets swept under the rug so quickly that I immediately suspected that there was something (ha ha) afoot. But no, we’re meant to be content with a completely unconnected mystery, centered around Amanda Abbington’s Mary Watson and starting with the case of “The Six Thatchers”, from the original “Six Napoleons”. The solution of the original case is the jumping-off point for a larger search for the truth about Mary’s past, which turns into a somber spy thriller closer to le Carre than to Conan Doyle, culminating in Mary giving her life so Holmes can solve the case.

An interesting direction, to be sure, and an unexpected one, but in hindsight it shows the same problem Moffat has been struggling with for years on Sherlock’s sister show Doctor Who: A fetishization of ending and change, coupled with a devotion to the status quo. Sherlock and John simply must be solving impossible cases out of 221B Baker Street, but the show has no idea how to have stakes, other than threatening that state.

This put the show’s very nature in a strange limbo in the next episode. With her killer utterly forgotten, Mary shows up in the flesh as a spirit guide to John (more mental representations!), granting exactly enough insight to push the episode’s plot along whenever it’s necessary. The inspiration for that plot is not from any Doyle story but The Seven per Cent Solution, the novel by Wrath of Khan’s Nicholas Meyer: A mystery where the question is Sherlock’s ability, rather than the actual facts. Sherlock fixates on an abrasive yet philanthropic public figure, played to slimy perfection by Toby Jones, and suspects that he is a serial killer. His evidence is iron-clad – that is, it looks that way to Holmes, and to the audience, but we know not to trust what to see onscreen anymore. Could Sherlock be going mad, and obsessing over some random guy on TV?

As it turns out, the man is guilty as charged, but that resolution doesn’t address how thoroughly the show has undermined itself, that there was ever a question: When we’re asked to take nothing we see at face value, having actual mysteries that the viewer can follow is no longer tenable.

To prove that point, the season’s third and final episode jettisons the entire concept of being a mystery program. You see, the reason so many people doubt Sherlock’s judgement couldn’t have been his fault, no way. It simply had to be the machinations of a devious villain. Who? Well, it’s teased throughout the season that there’s a secret third brother of Sherlock and Mycroft, based on a well-loved “biography” of Holmes that had his name as “Sherrinford”. It’s teased so heavily, in fact, that by the time Watson starts picking up on the clues it’s obvious there’s something else going on.

To contextualize this “something else”, we need to go back a little: Noted hot take vendor The Guardian published a review of the season the day the first episode aired, with the header “Sherlock is morphing into Bond. This cannot stand.” Clever-clogs that he is, Mark Gatiss responded with a quite well-crafted poem:

“There’s no need to invoke in yarns that still thrill,

Her Majesty’s Servant with licence to kill

From Rathbone through Brett to Cumberbatch dandy,

With his fists Mr Holmes has always been handy.”

Clever, true, but sadly irrelevant, since the real problem with this season of Sherlock turns out to be all the worst problems with Skyfall and Spectre rolled into one. “Sherrinford” isn’t a secret Holmes brother, it’s a sea-bound prison only barely more realistic than Azkaban, home of the brilliant and unhinged secret Holmes sister!

Wow, my god! Who could have seen this coming, other than someone who was reasonably familiar with Steven Moffat’s work, since he’s done the “it’s really a woman!” fake out more times than I can remember?

But yes, this sister has been masterminding events too far back to be elucidated, all to…unnerve and scare Sherlock, I guess? Fool the audience, maybe? Within the episode, there’s no real agenda to speak of, and the majority of the run-time has Sherrinford become a gauntlet of various torture rooms both physical and emotional, straight out of a Saw movie down to the vaguely retrograde message of it all – in this case, the whole “madwoman in the attic” thing, not ultimately meaning much more than it did in Jane Eyre. At the end, a large portion of the episode’s events turned out to not be real, because of course they do. Consequently, Sherlock and his evil sister have what’s supposed to be a touching reunion, and all the time I was wondering “How is the audience supposed to feel about this?”

I couldn’t think of an answer, I couldn’t solve the mystery. That’s just about the only genuine mystery there was all season long – the show has literally lost the plot, its identity becoming subsumed by its own quirks and its popular image. I’m sure the show will go on, but Sherlock as we know it – the harbinger of peak TV – is as gone as Moriarty.

Sherlock is available to stream on the BBC iPlayer or PBS. For an alternative, go to HBO and try True Detective’s first season, which features an exasperated everyman who teams up with a callow savant to solve a complicated, literature-inspired mystery.