Netflix, Amazon Prime, HBO, and various other streaming services have revolutionized the way we consume movies and television, and each week I’ll highlight the best these services have to offer in this segment: Stream of Consciousness.

In the early days of cinema, the movies were seen as mere entertainment rather than serious works of art. Films longer than an hour were a rarity, and the narrative scope of a film was significantly less than would be expected of a novel.

D.W. Griffith’s 1915 epic The Birth of a Nation changed all of that with what can be described without hyperbole as one of the, if not the, most important films of all time. The film is as revered as it is controversial, and it begs the question: Can great art also argue for evil?

Based on the Thomas Dixon, Jr novel and play The Clansman, The Birth of a Nation depicts the fates of two families, the Camerons and the Stonemans, during and after the United States Civil War. The Camerons are plantation owning southerners, whereas the Stonemans are Abolitionist northerners (patriarch Austin Stoneman is loosely based on Thaddeus Stevens). The film’s two halves center around these two families during the Civil War as well as the Reconstruction period following the war, including the tension between the north and the south and the eventual rise of the Ku Klux Klan.

To discuss this film without at least discussing the deep seeded racial issues of the film is impossible in 2016. The film has a cancerous, blackened heart pumping a racist sludge throughout its veins, and The Birth of a Nation wears that as a badge of honor. There’s no escaping the fact that the film glamorizes the antebellum South and portrays black slaves as happy working as housekeepers and cotton pickers. Sadly, those portrayals are among the more racially sensitive aspects of the film, as scenes featuring aggressive and seemingly brainless black men are littered throughout, often portrayed by white men in blackface. Even little moments like showing a slave whose entire existence is to work a plantation field need to have the process to be explained to them is a profoundly racist and unnecessary moment that solely exists to promote white supremacy.

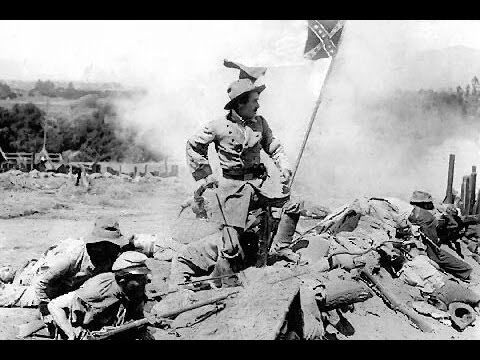

With that caveat being said, the film is visually stunning, particularly the Civil War-centric first half of the film.

Griffith utilizes and revolutionizes many filmmaking techniques, and the film feels fresh despite it being over a century old. The editing, cinematography, and visual storytelling on display is masterful, and the techniques can be directly traced to the films of yesterday and today. Griffith’s use of close-ups, fading cuts, vignette shots, and the scale of the battle scenes were unheard of prior to the film’s release, and became staples of the cinematic landscape ever since. The film doesn’t just use these tools to be flashy. The scenes featuring these advanced stylistic touches are all used to enhance the scene, such as the use of vignette shots to both emphasize an aspect of the frame, such as singling out John Wilkes Booth prior to the Lincoln Assassination scene, or to create an air of claustrophobia, such as when the Cameron women are hiding from the Union soldiers under the floorboards.

Aside from the revolutionary aspects of the film, the movie has many moments that are enjoyable to watch despite its horrendous politics. The first half of the film, depicting the Civil War, is a masterpiece in and of itself, and features the films more tender moments and avoids many of the racial pitfalls of the Reconstruction Era second half.

Griffith is a masterful director whose use of cinematic language is as in touch with contemporary tastes as it was in 1915. It is clear why a film like The Birth of a Nation would go on to inspire cinematic titans like Orson Welles, John Ford, Cecil B. DeMille, and Stanley Kubrick, as the use of the camera is as important to the film as the actors and script.

For all of his importance and artistry, Griffith cannot escape the legacy that he and The Birth of a Nation share. The film inspired hate crimes, white supremacy, and the eventual rebirth of the Ku Klux Klan, who had been extinct for decades since the reconstruction era. Seeing the glamorization of the Klan’s origins inspired surviving former Klansmen as well as (at the time) modern white supremacists coaxed by the film’s portrayal of the Civil War and the atrocities of the reconstruction era.

The controversial nature of the film created a cinematic event unlike anything that has been seen since. White Americans flocked to theaters in masses, while outside NAACP members protested the film’s racially insensitive depiction. The NAACP eventually attempted and failed to ban the film in the United States, while at the same time the flames were fanned even further by The Birth of a Nation being the first American film to be screened at the White House by then President Woodrow Wilson. The polarizing reaction to the film inspired Griffith to release the 1916 film Intolerance as a rebuke, rather than an apology to African-Americans and others offended by his previous film.

I watched the majority of The Birth of a Nation in awe of its cinematic techniques and unexpectedly mature views on the atrocities of war. I also spent a lot of time rolling my eyes at the minstrel show-esque qualities of the film. It’s a difficult movie to watch through a modern lens (It’s impossible to ignore the fact that the film was racist for 1915, let alone 2016) and it would be understandable for modern audiences to avoid the film like the plague, particularly people of color given its problematic nature. However, those who manage to look through the more despicable aspects and themes of the film will be treated to a piece of cinematic history and a work of art unlike any other.

The Birth of a Nation is available to stream on Amazon Prime as well as on YouTube. Next week, we’ll continue to look at the historical timeline of the largest box office films of all time with Steven Spielberg’s 1975 horror classic Jaws.