It has been a year and a half since my departure from the armed forces. This process of reintegration has been an unusual voyage, and with each passing day comes the growing realization that there is never truly any going back. That isn’t an admission of defeat or surrender to doom, however. As I chart the next course in my life, I take in both my experiences at war and a new understanding of the world around me to try and move forward.

Film continues to be the powerful medium that best helps me process the conflicts in my mind and soul, and I’d like to share with you some recent insights on this Veterans Day. In my prior essay, I chose to focus mainly on what I refer to as Modern War movies, whose subject matter usually takes place in our contemporary context. As it happens, there are several films this year situated on older conflicts of generations past that are still significantly relevant to this day and age, so I’ve broadened the scope of my analysis to try and get to a deeper understanding of where we are now as a society, and where I am as a human.

I. The Passion of the Grunt

The first half of this year yielded some rather unfortunate movie viewing experiences in the arena of cinematic modern warfare. I began with Mine, an action drama starring the talented but often misused Armie Hammer as Marine Sniper Mike Stevens, trapped behind enemy lines in a deadly predicament. During the egress from a botched assassination mission, Stevens steps on a landmine and is stuck in place. Throughout his attempts to break free, outside forces and inner turmoil begin to overwhelm him.

The film reveals itself as an incredibly strange vision quest, exorcism, intervention, and hoorah action movie all rolled into one. While this sounds fascinating on paper, the proceedings amount to an excruciating Hallmark movie, replete with domestic violence, daddy issues, hero worship gun wanking, and its very own exotic Magical Negro. What movies like these American Sniper rip-offs fail to understand is that you can’t praise the hero’s redemption if you continuously glorify and excuse the actions that condemn the character in the first place.

The Wall doesn’t fare much better, though it suffers from its own set of problems. In it, Aaron Taylor Johnson and fan favorite wrestler-turned-turned actor John Cena star as Army Sergeants Issac and Matthews, a sniper team pinned down by a deadly enemy expert marksman. The film starts off promisingly enough, with an interesting premise and true to life camaraderie between the two characters that make you feel at least somewhat invested. What begins as a tense and realistic sniper standoff movie gradually mutates into a bizarre psychological thriller/slasher flick.

The enemy sniper never appears on screen, instead represented only via radio chatter. British character actor Laith Nakli voices the role with an impressive malleability and charisma (especially evident compared to Kick-Ass, who quickly becomes grating and insufferable as the story proceeds), but that’s what makes the conceit so very disappointing. For a movie that is told in large part from the literal POV of an Iraqi citizen having to contend with what the American invasion/OIF has done to his country, the movie completely wastes its opportunity to say anything meaningful about the conflict. Instead, we are subjected to yet another tale of martyred American soldiers. The wildly bleak ending almost makes up for it, but by then it’s too little, too late.

I witnessed yet another well-meaning but ultimately disappointing screed about our modern conflicts in War Machine, a semi-fictionalization of General Stanley McChrystal, who resigned in scandal after his disparaging remarks about President Obama’s administration were made public in a Rolling Stone magazine exposé and subsequent nonfiction novel. Brad Pitt stars as General Glen McMahon (renamed as such in this adaptation), the newly appointed commander of allied forces assigned the impossible task of winning the war in Afghanistan. Accompanied by his brash cadre of senior officers, capable junior soldiers, and crafty civilian advisor, McMahon tries to break through the quagmire of convoluted politics and corruption with an old school hard-charging approach. But with such a bold leadership vision (or delusions of grandeur depending on your point of view), he is unable to accept the ground truth of demoralized soldiers fighting a war with no clear objective and a populace that doesn’t want his kind of help.

While there is certainly an absurdity to be gleaned from the situation, the film is an unfocused mess that can’t decide if it wants to be a poignant morality tale or screwball comedy. Pitt’s bizarre mannerisms might work if the film was a straight up darkly satirical comedy a la Dr. Strangelove, but the harrowing exploits of young marines highlighted by yet another brilliant performance from rising star Lakeith Stanfield make for a tonally confused waste of time, time that would be better spent studying the real life source material.

More recently, I watched Thank You For Your Service, based on the nonfiction book of the same name that examines the lives of soldiers back home in the US as they struggle to readjust to family and civilian life after their combat tours in Iraq. This film fares marginally better than the previous films, taking the issue of PTSD seriously thanks in part to a great cast. In particular, while I wouldn’t call myself a fan of Miles Teller, the role of the modern square jawed middle American soldier sporting internal and external scars suits him quite well.

There are a lot of good things in Thank You For Your Service to appreciate, but in the end it feels rather guileless. The tangible accurate details grind up against sappy melodrama and questionable dramatic choices that make for an uneven experience; I groaned and rolled my eyes about as many times as I nodded in agreement or teared up at something poignant. I had presumed that the general public might be more receptive to the film as its one of the more “digestible” modern war movies, but it’s underwhelming box office results seem to refute that estimate. A solid attempt worth checking out and discussing nonetheless.

II. She Can Do It!

While the grizzled bearded combat veteran cinematic output of this year was lackluster at best and downright fetid at worst, I was overjoyed to see stories about women and their combat experiences lead the way as some of the best films of this year, war oriented or otherwise. The criminally underappreciated Megan Leavey was leagues ahead of the aforementioned disappointments, eschewing overwhelming bombast and soul wrenching tragedy for a subdued meditation on finding purpose and healing. Kate Mara stars as the titular Marine, playing through the real life exploits of the MP K-9 handler and her heroic military working dog Rex. Even though the movie contains many beats familiar to stories about women in the service and relationships between (wo)man and dog, Megan Leavey finds a harmonious balance between cliché and authenticity, another noteworthy example of finding the universal in the specific. The scenes detailing the duo’s tours in Fallujah and Ramadi are tense and realistic, showing the grim reality and grey morality of the war without ever proselytizing in any one political or religious direction. There is a candid love story that unfolds, but this too escapes any stereotypical mundanity one might dismissively expect from a female-lead war movie. Her struggle to readjust after her service rings true, and her resolution to rescue the decommissioned Rex –also suffering from PTSD of his own- from being put down is at once a uniquely gripping drama and a testament to overcoming trauma with love and support that everyone can learn from.

Things get kicked up a notch with the terrific feature Blood Stripe, which is simply one of the best explorations of combat trauma that I have ever seen. The film stars Kate Nowlin as a female Marine who the audience knows only as “The Sergeant.” She is as fierce and imposing as she is obviously wounded and broken after a combined 3 combat tours in Iraq and Afghanistan. Haunted by an unspoken trauma, she recedes from her her well-meaning friends and family at home who can scarcely fathom the depths of her nightmares. The Sergeant winds up seeking refuge in the remote summer camp of her youth, and while she befriends sympathetic strangers eager to ease her pain, the ghosts of war slowly begin to sabotage her search for peace.

Blood Stripe touches on an extraordinary facet of modern warfare little known to the public at large, as we learn that The Sergeant was part of the elite Lioness Program, female Marines assigned alongside combat troops to conduct checkpoint searches and outreach operations with Iraqi women. She also served as part of a Female Engagement Team (FET) in Afghanistan, designed with a similar purpose to appeal to the cultural customs of their host nation in the hope of fostering better tactical and strategic relations. With such indelible combat prowess, The Sergeant remains constantly on edge, and that tension is palpably brought to life on screen. I’ve spoken before about how horror films can be a powerful means of expressing combat trauma, and Blood Stripe does a masterful job of incorporating those elements into the later half of the film. The Sergeant, in her sparsely populated summer camp, all at once turns into and attempts to flee from the Voorhees-esque serial killer stalker that her wartime demons make manifest.

In the realm of big budget fare, the long awaited feature length live action adaptation of DC Comics’ Wonder Woman surprised and enthralled moviegoers around the world with its high flying superhero spectacle from a uniquely female lens. I’ve found that although I generally enjoy them, I’ve become less enthralled by superhero/comic book movies with each passing iteration. Wonder Woman shares the same problems with many films of its ilk, but it still manages to be a breath of fresh air in the current blockbuster landscape while also giving a huge boost to the floundering DCEU project. A colorful palate, outstanding casting, and its setting during The Great War of the early 1900s that is seldom seen in big budget movies sets it apart from its contemporaries. Moreover, it uses its comic book origins about a race of female warriors and its WWI setting to take some fairly deep dives into themes such as sexism, racism, and the total destruction of war that engulfs mankind physically and spiritually. Though not a modern war movie in my strict original sense, Wonder Woman has lessons for us about war and its associated evils that we would do well to heed today, wrapped up in an entertaining and empowering tale for all ages and genders.

I also want to give special recognition to the World War II comedy/drama Their Finest starring Gemma Arterton as Catrin Cole, a young British writer trying to make her own way in a man’s world while also doing her part for the war effort during England’s darkest hour. Catrin is recruited by the British Ministry of Information to write scripts for propaganda films, specializing in writing “slop”, the term used for women’s dialogue deemed insignificant compared to the grander idea or product being pushed. Seeking a more worthwhile tale, she investigates a story about a pair of sisters who attempted to be part of the famous civilian rescue of stranded soldiers at Dunkirk. The ministry catches on to the story and green lights a film production of the event, but sexist institutional attitudes and external political pressures yield a story wildly divergent from reality.

Catrin fights a two-front war for the recognition of her own capabilities as an intelligent woman and as an artist fighting for artistic integrity and the truth. All the while, she must also contend with the shooting war that surrounds them all, as the German bombing campaign escalates and threatens the lives of her, her companions, and the entire nation. At times, I was taken aback by how maudlin the film could be, having an almost TV-movie lightness about it, particularly with some of the more distracting musical cues. Despite this apprehension, I was eventually overwhelmed by the charm, enthusiasm and honesty on display. Like Wonder Woman, Their Finest understands that truth, wisdom and above all love are just as important in our battles as any military might, for they are the very things worth fighting for in the first place.

III. Those Who Cannot Remember the Past…

Speaking of Dunkirk, this year saw the debut of the highly anticipated film from renowned director Christopher Nolan based on the famed incident. Dunkirk is in many ways an experimental type of project, a movie that plays with our perceptions of time and well worn conventions of traditional war movies. Its modern relevance rests not only in its technical craft, but its thematics as well. Although time becomes fluid, our objective observations of how the events play out remain clear, whereas the characters glean substantially different understandings about the same event based on their point of view within the movie’s space/time continuum and their own fragile emotional states. The final act also touches on the lies we tell to ourselves and each other in order to persevere, along with the individual truths we recognize that others around us are unwilling or unable to accept. In our current political climate fraught with subterfuge, coverups, fake news and the concerns about what that term really means, this meditation on perception is quite relevant.

It was also fascinating to see serious conversations external to the film’s narrative that nonetheless hold significant weight. On the topic of racial representation in movies, there were many arguments about the veracity of the virtually all white/Caucasian cast compared to the many soldiers from different nations and ethnic groups subsumed by the British empire into its wartime ranks. The very act of questioning the potential erasure of diverse peoples in what was until now thought to be accepted history is itself an important step for war movies in particular and film in general, that we might reevaluate when necessary to come to a better understanding of our past endeavors for all their good and ill.

This brings us to another terrific film taking place during WWII and its aftermath that is one of my contenders for best film of the year: Dee Rees’ epic drama Mudbound. The film is based on the award-winning 2008 novel of the same name, detailing the lives of two families–one white, one black–in the Mississippi delta during the 1940s. The McAllens are educated urbanites facing the increasingly harsh realities of maintaining their new farm. The Jenkins are a family of sharecroppers living on the McAllens’ land, the very same land that their parents and grandparents once toiled on under the yoke of slavery. As a young man from each family is sent off to the war, the families experience shared trials and tribulations, forming a tenuous bond. Upon the return of their soldiers, the terrors of the war and dark secrets of the past build up to a breaking point, the likes of which can only end in pain and tragedy. Mudbound deftly weaves its themes of racism, poverty, jealousy, family rivalry, and PTSD into a cohesive and spellbinding whole. Featuring a murderer’s row of onscreen talent and supremely impressive skill behind the camera, the movie truly feels like a great American novel come to life.

Garret Headlund’s turn as Jamie McAllen really showcases how drastically war can change a person, the sharp and charming playboy being reduced to a barely functioning drunkard by his experiences as an Air Force bomber pilot. The graphic flashback sequences in the B-17 cockpit are brief but effective, displaying the very unique hell of frost, flame, and blood that pilots of the time endured. At the same time, the film also speaks to the psychological schism that technological advancements of warfare incur when we see Jamie tormented by the realization that he can never truly know just how many people he has killed from 30,000 feet in the air. Pilots continue to endure this schism, and it is particularly true of our modern UAS pilots, completely removed from the danger of combat yet responsible for major portion of the deaths involved.

Jason Mitchell adds another outstanding role to his career as Ronzel, a kind and loving young man forged into a fierce warrior in the hellfire of the European front. Ronzel is part of the legendary 761st Tank Battalion, a segregated combat unit of African-American soldiers known as “The Black Panthers” who were integral to many victories in the push into Germany. Over There, he is lauded as a liberator and honorable man, falling in love with a Bavarian woman who recognizes his inner beauty. However, the end of the war means a return home to the life of a second-class citizen, regarded as less than human by the very country he fought for. Ronzel’s reintegration is doubly tragic in that his combat stress leaves him constantly on edge and eager for a fight that he can never return to, yet unable to fight back against the cruel racist injustices of the white men at home, lest he and his family face certain death. As a black veteran with three deployments returning to a nation boiling over with racial tension, this story resonated quite deeply with me. Though I haven’t faced Nazi Reich or Klan lynching outright (though that is sadly and disgustingly becoming more and more a possibility), I must still contend with the sobering reality that statistically I am more likely to be killed by a cop than a terrorist.

IV. Through the Lens of Reality

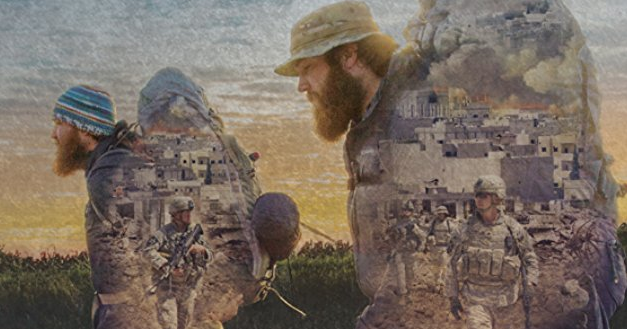

While the process of consuming and critically engaging with fictional media can make for an enriching experience, we must never forget the importance of taking in real life first-hand accounts, especially in matters of war. In this regard, there are a few documentaries released this year that I would consider vital viewing. Almost Sunrise tells the story of two former soldiers who go on a physical and metaphorical journey in the hopes of finding relief from the pain of their wartime traumas. In late 2013, OIF veterans Tom Voss and Anthony Anderson made the 2,700 mile trek from Milwaukee, Wisconsin to Los Angeles, California entirely by foot, raising awareness about PTSD, suicide prevention and veteran mental health issues along the way. Acclaimed director Michael Collins chronicles the journey, interspersing interviews and clips throughout the film that reveal the depths of each hiker’s agony.

Almost Sunrise examines the concept of “Moral Injury”, where the very act of violating one’s moral codes and sense of human decency through action (or inaction) incurs a tremendous strain which yields as significant a physiological effect on the warfighter as any physical stress or graphic sensory overload. Near the end of their trek, we learn that as one man experiences profound change and rejuvenation, the other still seems haunted by something he can’t let go. A moment of deeper internal reflection during their walk leads to the realization that it is a spiritual journey that must be taken more than a geographical one, a journey where forgiveness becomes the real destination. Although Almost Sunrise had a very limited release, people nationwide will get the chance to see it free of charge when it airs on PBS on November 13th at 10pm on your local broadcast station and online at http://www.pbs.org/pov/almostsunrise/ . Please be sure not to miss this one.

As it happens, there is another film called Thank You For Your Service released this year, but this time it’s in the form of a real world documentary exploration of the failing Veterans Affairs (VA) health care system. The film shares the stories of several former Marines diagnosed with PTSD and their desperate struggle to survive it, while also featuring a heavy dose of facts and figures from military doctors, journalists, healthcare professionals, celebrity activists, and even the highest levels of leadership with commentary from former Joint Chiefs of Staff Chairman Admiral Michael Mullen and former Secretary of Defense Robert Gates. Thank You For Your Service also delves into the phenomenon of moral injury, though its main focus lies in documenting the specific problems of the larger healthcare system while posing several possibilities as ways forward.

Like the soldiers in Almost Sunrise, the Marines featured in Thank You For Your Service eventually reach breakthroughs in their recover by more unconventional holistic methods such as meditation and bonding adventure excursions, expelling the bottled-up demons that no pill prescription or overburdened social worker could hope to extract so easily. The documentary advocates for much broader approaches to treating PTSD, while also campaigning for what one doctor calls “the Behavioral Health Corps”, a way to put these varied techniques into the hands of warfighters in an organized institutionally funded and directed manner. It remains to be seen if this campaign will succeed, but Thank You For Your Service is nonetheless an eye opening work that officials at all levels should take heed of.

Perhaps the most concerning and longest lingering problem with our modern warfare media is our adherence to one particular point of view, that of the American/Western Warfighter and the organizations orchestrating the conflict in which he fights. At the very least, we must be able to recognize the myriad deadly large-scale and small-scale conflicts happening throughout the world, particularly ones where we are not necessarily the primary combatant force. The crisis in Syria is among the most significant of these, with the international terrorist organization known as the Islamic State or ISIS/ISIL seeking to use the war-torn nation as a springboard for their worldwide campaign of death. The documentary City of Ghosts is a superbly crafted look into this conflict; it is quite simply the modern war film that the whole world needs to see.

The film centers on an incredibly brave group of Syrian civilians turned political activists who take on ISIL with words rather than weapons. Syria was embroiled in a devastating civil war in the wake of the Arab Spring, with significant portions of the country liberating themselves from the Assad regime. In the resulting power vacuum, ISIL forces quickly took power and seized the Syrian city of Raqqa as their de facto headquarters. The civilians who once documented the atrocities of the civil war now turn their cameras onto the inhumanity that ISIL inflicts upon their city. The small crew brands themselves as “Raqqa is Being Slaughtered Silently”, a full fledged journalist organization committed to showing the truth of ISIL’s barbaric occupation that the terrorists seek to hide. These acts of defiance have deadly consequences, and the film follows along with the journalists as they seek refuge from assassination while trying to garner an even larger international audience.

In this era of cyber-warfare, Wikileaks, and political collusion, information has become more critical than ever before in matters of defense. ISIL, with its bleeding edge propaganda apparatus, understands well that the pen is indeed mightier than the sword, and will stop at nothing to silence all opposition. RBSS shows to be just as capable as any nation-state intelligence agency with its network of spies and insiders. Likewise, ISIL employs sophisticated technological countermeasures in concert with their medieval savage coercion methods to close in on the activists. City of Ghosts exhibits an entirely new type of warfare that we can scarcely wrap our heads around. A typical American combatant with boots on the ground might fight for freedom and security in an esoteric sense, but they usually aren’t concerned with directly protecting their nuclear family from the insurgent in their cross-hairs. Such a situation can’t possibly compare to the abject horror we observe when an RBSS Journalist witnesses his father in chains, forced to renounce his own son, followed by a summary execution where he is murdered via several bullets to his brain and body in a 4K Ultra HD big budget production for people around the world to see streaming on their laptops and mobile devices. This is what war in the digital age looks like, and we must not avert our eyes from those on its newly defined front lines.

V. The Journey of a Thousand Miles Begins

Something has been happening inside me over this past year and a half, and I don’t quite know what it is. I think of all the movies that had profound effects on me and I try to suss out what they are pinging on, but the excavation is a slow-going and laborious endeavor. I get angry. A lot. More than I used to. I can feel it eating away at me and possessing my interactions with others. I’ve come close to violent confrontations more times than I care to admit. My loved ones confided in me their dismay at my standoffish demeanor. And online, especially online, I can feel the venomous invective dripping from my words whenever I get worked up over a stupid internet argument.

I’ve always made it known that I was never combat arms; my service instead consisted of long hours at a desk behind a computer screen doing what I could to support the guys on the ground. So why do I feel such anxiety? Maybe it’s because there were other POGs just like me who got obliterated by indirect fire and I wonder why I got home safe. Or maybe it’s because I was ashamed of being a fobbit while there were guys out there more capable and intelligent than me putting themselves out there in harm’s way, only to have a molten hot EFP copper slug bore through their chest. Maybe it’s because my fat fucking knees gave out and I couldn’t hack it anymore. Maybe its because I subconsciously resent having someone who loves me with all their heart, which means I’m no longer just another expendable bastard, so now some other poor kid still wet behind the ears has to take my place in a war that should have ended years ago. Maybe I’m waiting for an officer of the law to befriend who I can share war stories with and finally get over this phobia. Maybe I’m waiting for an officer of the law to put two in my back and have the news broadcast my pretty dress uniform with the bronze star on it to make people understand exactly why football players choose to kneel. Maybe I just need a little change.

Now that I have my GI Bill, I’ve begun my first semester at a bonafide university. I’ve been writing for a long time, but now I’m finally learning the academic component of ideas and issues that I understood intrinsically but can now expound upon with more complexity. The readings of Barthes, Jameson, Carey, and Sapir are illuminating concepts in ways I couldn’t imagine. All told, I’m actually doing quite well so far, and it is my hope that my continued academic success will bring me peace of mind just as much as a foundation for a steady career. In learning about these levels of mediation between ourselves and the media we consume, I’m also continuing to reconcile with all my past deeds and experiences in relation to what is being put out there for the public to see. I hope that with this accumulation of knowledge, I can help people better understand war as we know it while also gaining a better understanding of myself. All in due time, but I have at least taken the first steps, and I thank you all for following alongside me.