The following is part of a series of articles that record the process as I develop a horror film titled Wrath. These are not meant to be treated as educational documents but rather a glimpse into the creative process of a single filmmaker. Every writer, every filmmaker has their own process.

The first entry can be found here.

This time I explore my relationship to a complex character, authenticity over granular detail, improvisation and intuition over micromanaged plotting and the need to move beyond narrative constructs.

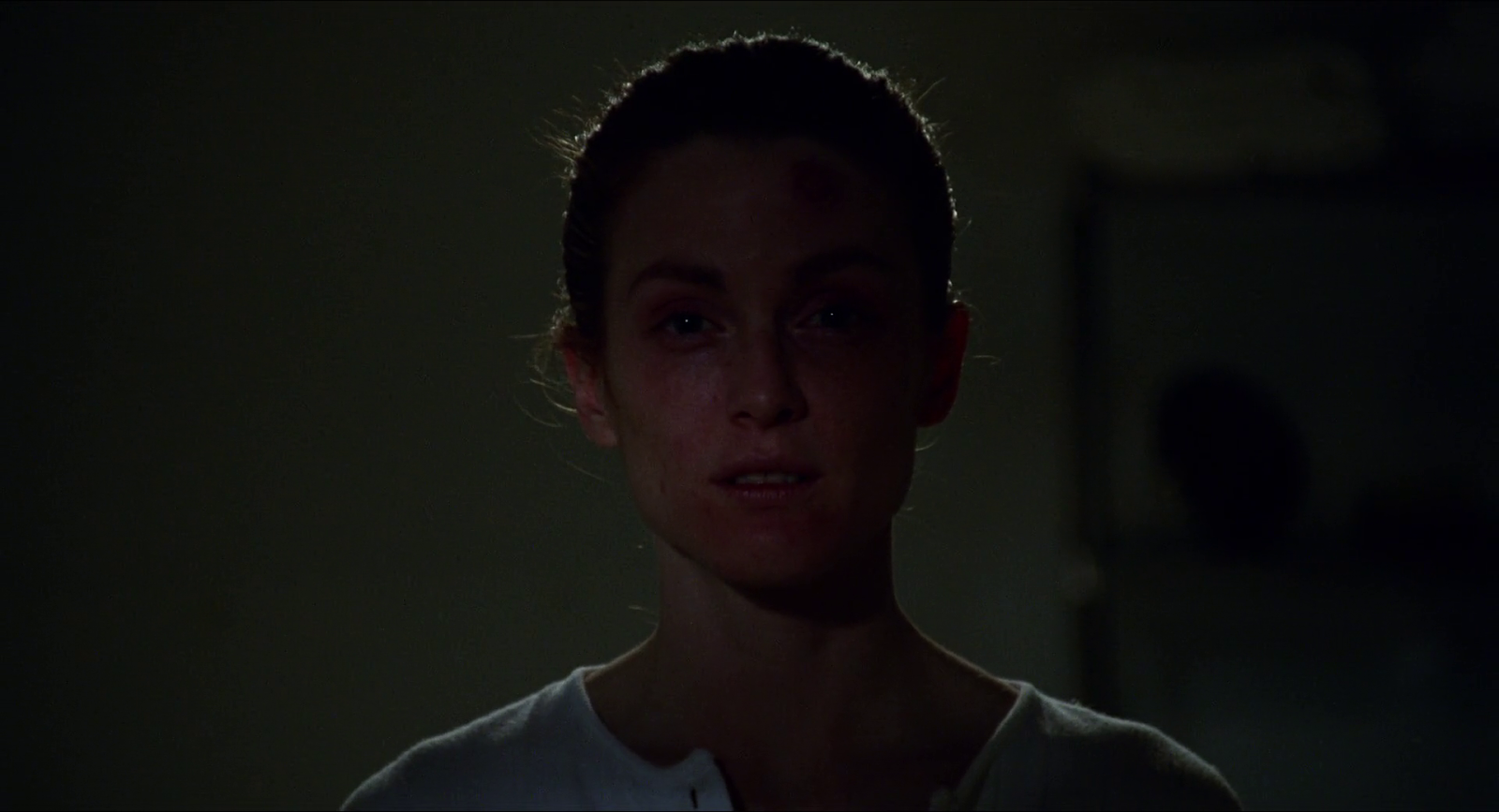

Part 3: Falling in Love with Samantha Ward

The most crucial part of any story is character. Not plot. Not ideas. Character. Entire movies live and die based on how compelling your central characters are. Why? Because we are social animals, we seek faces in inanimate objects and anthropomorphize our machines to make connections on a personal level. There is a belief you don’t need to know every major detail of a character and they just need to act in relation to the plot. I disagree. I approach characters as if they are real people because I need to know and love them in order to understand what kinds of decisions are appropriate for them. To treat them as narrative constructs is to turn them into pawns in service of the plot, which undermines our capacity for empathy because we can tell when a character decision is not organic to the scene. We need to love our protagonists, and in the case of Wrath this is Samantha (Sam) Ward, because if we aren’t totally invested in her, then why are we watching?

I built Sam out of a triptych developed by Lajos Egri. Three Categories: Physical, Sociological and Psychological. Each segment is a list of complex character traits based on their headings. Each element, from appearance and fashion to social standing or personal emotional hang ups are interconnected and built off each other through a complex character history we create. This backstory does not need to be referenced but it is good to have in order to provide contexts when I “play” the character as I write. If I know that an element of her past or present would mute a reaction or cause an extreme response, I need to keep that context in my mind. A character is a rule, a limitation on the script’s world. You can’t break Sam to make the story move. Your audience will know and reject this as implausible.

But why and how can I love Sam Ward? Because she is me in many respects. My writing is often a reflection of my interior landscape, what I know to be true and what I know to be bullshit. I have to love my character because she is me, my Anima in a loose sense of the word. I understand every frustration and fear and anger because they are my own, twisted into fictional form. Fear of control, fear of loss of identity, fear of not being able to live as I want to. And to burst away, using any means possible to create a true self is something deeply important to me.

My character also does some truly terrible things in the course of this story. But I still love her… A lot of my films are built around the nature of heroism and empathy. That heroic character tropes aren’t simply there as straight things, and their compulsion to do good things comes from a darker, deeper desire to fill something missing. So a lot of my protagonists end up skirting the fringes of traditional “likability,” making them a kind of anti-hero. And they are presented with a moral line. And for me, the moral line is not the climax of a character’s journey, but the beginning. I don’t find much dramatically interesting in that supposedly crucial choice because it’s binary and posits a world functioning around hardened notions of good and evil, and there is always a supposition that the character will make the right choice by steering away from the dark. For me what’s far more dramatically fertile is crossing the line. That all heroes come across that dividing line between their goals and ethics/morality in search of the solution to the problem they think they want to solve. So they run past the dividing line of day and night and into the dark to pursue their goal. Good intentions pave the path to hell and what not. What I find interesting is our character’s journey back from the dark, and their attempt to answer the question that most plagues them: can I go back to day? Will they be able to go across the line again, or will the line have been lost? Are they forever trapped by their decisions? Or, is it that the line never really existed and moral compromise was an inevitable consequence of the path they chose? Sometimes there is no daylight at the end of a journey, but there is still a sense of satisfaction even getting back to twilight. We need to see where their breaking point is and press until they either shatter or bend, and to see if they can return to form.

At the same time, apparently contradicting what I said above, it is important to understand that building too much exhaustive detail into a character is actually detrimental to the creation of a living breathing character. To go beyond understanding how a character responds to their journey and into an exhaustive catalogue of traits is to dissolve that character from a living person that exists in the mind into a dead list of points to cross-reference. Detail is important for authenticity, but too much detail dissolves the character into rote data work. We need to understand them and understand that there are some facets that are mysteries even to the characters themselves. Why? Because knowing a character intimately is to know they will always surprise you.

This is a lot flowery language that describes an imprecise, fluid process that is governed largely by intuition. It is too difficult to elucidate this because it’s not a truth that can be taught. It’s something I and I alone came to because it is something attuned to my process. Other writers can create fantastic works without needing to adhere to these concepts and from what I gather, most don’t do this. Why? Because there are actually no rules. I’ll clarify this point at the end of this journal.

Part 4: Building Setting as a Character

We tend to see settings as perfunctory set dressing because we often disregard them as mere backdrops in which we place our drama. This has always struck me as counterintuitive because it views the primary dramatic force of a script to be rooted in dialogue, driven by talking rather than action or place. Personally, I find this take on the material comes from an outmoded belief of film as recorded theatre. The world as backdrop suggests the proscenium arch is still in the back of peoples’ minds.

In truth, settings are a kind of character unto themselves, containing a similar nuance and capacity for change but rooted in the subtextual rhizomatic pathways navigated through the locations by the characters of the films. And for these characters, like Sam, spaces like the primary location of the short, the suburb/gated community of Brennan Fields, are built on the same triptych of physiological, psychological and sociological traits. However, these elements inform a largely passive body which the characters and their respective identities play within and against.

Because settings are most often passive characters they do not need the same focus and attention to detail as characters. Because worlds, beyond their defining traits and rules that can’t be broken, are by their nature vast complex systems, it is better to render them in broad strokes and impressions with pockets finer detail rather than focusing in on cataloguing minutiae. We do not need to know what exactly lies on the corner of Windemere and Huston and who lives there unless it is important to the stories and characters or drives the plot forward. What matters beyond realism is authenticity. Spaces are built by mood, tone, look, feel, overarching and immediate contexts and relationships to the characters. Who lives where, what designer furniture they decorate their house in detail best left to those who have the page count to make such things relevant in my personal opinion. Film is rooted in characters and characters alone.

This is the great failure of nerd and fanboy communities and their writing. They get lost in the granular details of world building and mistake it for relevant storytelling. The truth is as long as a space plays off a character, knowing irrelevant details are a useless gesture that slows writing down. Author William Gibson has referred to the worlds of his works as “High Resolution Surface;” The authenticity of the moment carries us forward with the characters and does not get bogged down in useless details is more important than figuring out what material some post apocalyptic steam punk city is made of.

The important part we should take from building a world is a complex understand of its affect upon a character and the rules that limit and govern them. Seething, brooding emotional undercurrents that in equal parts reflects and affects our dramatic subject. Fine grain world building doesn’t quite get across this need to convey space as a psychogeography, where a complex understanding is built around how characters live and react within it. It’s hard for me to be clearer, sorry. This is an imprecise art form. But basically, how I see it is that strong worlds are not found in details but the patchwork of emotions and conflicts it generates in our characters. These are things not always created in details and particularities but in understanding the space as a systemic, sociological whole and the cultural and subcultural structures that are engendered within the latticework of the community. The visual constructions and design really don’t mean that much unless it affects a character or the story.

Take, for example, a swinger’s club in the film’s town Brennan Fields. Say it’s taking place in Maggie Hofstadter’s home for that particular meeting. Do I need to know what street it’s on? Only if it contributes to the script in a meaningful way. It does not need detailing unless it directly informs our readers and us and enriches the story, conflict or character psychology. Film is largely a subjective, image-based medium. Though too many of us strive for objectivity in our storytelling, we see space through a character. Scripts should be written like that. The level of detail should only be as complex as the dramatic fulcrum (whoever drives the scene in that particular scene) sees it to be. If, say, Sam were to pass through this swinger’s club meeting and she was focused on the subculture, the description would reflect her attention to the people there, their sexual proclivities and actions, their faces, their social dynamics and so on. If her dramatic focus was on comparing her life to the Hofstadter’s, then our writing would be focused on location, size of house, decoration, taste, affluence, culture and so on. All the details about the swingers would be minor comparison in this case because it’s not what she wants us to see. We do not need to know everything simply because it is there, we need only focus on what details drives the characters, their conflicts and subsequently, the plot, forward.

Part 5: Plot, Structure, Ideas and Improvisation

From the two crucial factors, characters and settings, and the premise, I start building a plot. I write an outline of my script before I move forward. I always write in a notebook and not a computer as the use of my hand affects my memory of the written material. I don’t really care about predesigned structures and just start plotting from page one onwards. I create a version of what is commonly known as a step outline. This is where the nascent ideas and themes that helped birth this project is fleshed out as a series of single sentence story beats. I organize and plot to fulfill the basic narrative requirements to fulfill the ideas and themes and premises within the limits and contexts of the characters. I literally plot every thing down to the page with detail as to what happens and how we got there.

And then I step away. I step away for a good long while and I let the memory of my story soften and fade and become molded by my memory and understanding of characters. I let my characters colour and twist the story in my head until it is something I remember like a favorite movie from my past or a good story to tell around the campfire. Memory is a funny thing. Unless details form the basis of an emotional trauma, our minds have a way of clarifying and focusing in on the emotional realities of our past. We rewrite our stories to make ourselves the heroes. Details strip away focusing on the feelings and impressions we took from it. We distill a story down to its essence in our memory.

Structures are cold. They’re not really the heart beat of a storytelling, though they are a vital part. They don’t truly convey that raw story drive that pulls us into a movie. I think we place too much obsession and value on structure and it takes from character. These stories need characters to drive the action of the plot. I believe the characters should be at the forefront of our minds as we write. To beholden ourselves to a story plan instead of our characters leads to scripts that are to putting plot first, focusing only on giving us what we need to move forward and not give more insight into the people that make the story go. I call these “unpacked” narratives. Without a breadth of dramatic content to drive the work, we rely on plotting instead which creates scripts that are too functional, dry and lacking in flavor because we have stripped scenes to their bare dramatic necessities. There is nothing else to hold our attention and unless what we’re writing is absolutely riveting, it’s not enough to hold our reader’s focus. Film shouldn’t be so distilled and utilitarian. People mistake this functionality nonsense for narrative conciseness and create stories with stripped down, weak dramatic essentials that can’t carry you even 90 pages. We need to move beyond it.

Good stories are about relationships. We cover up the concise plot driving conflicts by layering in sub conflicts and narrative threads to compliment the main A STORY. We Must provide a depth and breadth of drama moving in parallel thematic and causal direction as the main narrative thread to create a movie with dramatic fullness. So I let my story sit and fade until I remember how the beats played out in relation to the emotional process of the characters and from there I improvise based on what I remember and not what I wrote.

An important element in this process is intuition and images. Sometimes scenes and sequences come to mea without reason, informed by the character and world I invented to create new content or just embellish scenes with new angles and ideas. It’s fluid and it works for me because this is my process. It’s something I developed through years of writing on my own. This works for me because it complements how I think. My way is not a definitive form or rulebook. In fact no way is. Because there is no rules to crazy process. Nothing at all. Guidelines exist to help you find your way again if you get lost in the woods but really, there is no real one way to do things other than practice and some basic formatting guidelines. We like to think there are ways to do something but there isn’t. It’s a lie to create homogeneity in our work because we are pushed to create similar material. In reality the best films break all the so-called rules and build their own way to creating important, emotionally affective stories. Rules are ultimately only important to you as a writer and you can’t bind yourself to arbitrary creative rules set out by someone else. If they do work for you, then your process is concrete and process based and that’s equally as valid as how I approach narrative. But what I do works for me and what process you develop should work for you.

Next week I start writing.

Additional Resources: Lajos Egri: The Art of Dramatic Writing (warning contains some sexist and racist assumptions within the text)