It’s been a long time since 1982. Ridley Scott’s revolutionary, influential Blade Runner has done just about all the revolutionizing and influencing it ever will.

Looking past the question of why you’d make a sequel after all this time – because let’s be honest here, we all know why – we come next to the question of how to deal with that fact. In this culture that’s been dining for so long on the fruit of Blade Runner‘s many branches, what does Blade Runner 2049 have to tantalize us?

Simply put, it has been taking notes on the competition. Ridley Scott’s direct influence is clear on the movie, but the director was film nerd sweetheart Denis Villeneuve of Sicario and Arrival, who’s always mindful of his audience’s expectations. Villeneuve fills the world of 2049 to the brim with hallmarks from the past three and a half decades of cinematic sci-fi. Pivotal moments are inspired by visuals and concepts from Terminator, Wall-E, The Matrix, Ghost In The Shell, and HBO’s Westworld. Whole scenes are copped from Her, The Hunger Games, and its own paternal cousin once removed Minority Report.

No, we don’t get to see a flying future-car assemble around Harrison Ford, fun as that would be.

I don’t mean this as a bad thing, not by a long shot: The key to worthwhile art isn’t not stealing, it’s stealing artfully and from enough places that something new is formed from the stew of it all. And “worthwhile” is, above all, how I’d describe 2049 — an achievement much more magnificent than it might sound.

Ryan Gosling might disagree about that: Our star and new blade runner 1 is beaten down by his illegal-robot-hunting lot in life, more like Clive Owen’s depressed lead from Children of Men than his selfish, gruff antecedent Rick Deckard. With the exception of Ana de Armas as his roommate, he’s completely withdrawn from the rainy, cyberpunk world of Los Angeles. This seems like Villeneuve’s touch. We get all the director’s trademarks (paranoia and confusion over one’s own nature, misty landscapes, shocking explosions) but that’s the most noticeable: The world of 2049 is held at arm’s length to the story, much more than Blade Runner‘s world of 2019.

Gosling trains you to watch his face like a hawk, acting so subtly you need modern cameras to pick it up.

Interestingly, the story’s events are much more concerned with that world: For all its philosophy and trailblazing design, the original was ultimately a relatively small-scale affair, a very classical film noir about organizations much too huge to fight, and people too smart and sad to try. Thirty years later everyone still alive has been worn down, by loss and natural disasters and new types of replicants and other details too sensitive to mention, that the situation has changed: The world seems small enough that it might be changed for the better. The actual fate of all people-shaped races could hang in the balance of Gosling’s mission – at least, that’s what his boss, played with a wry texture by Robin Wright, keeps telling him.

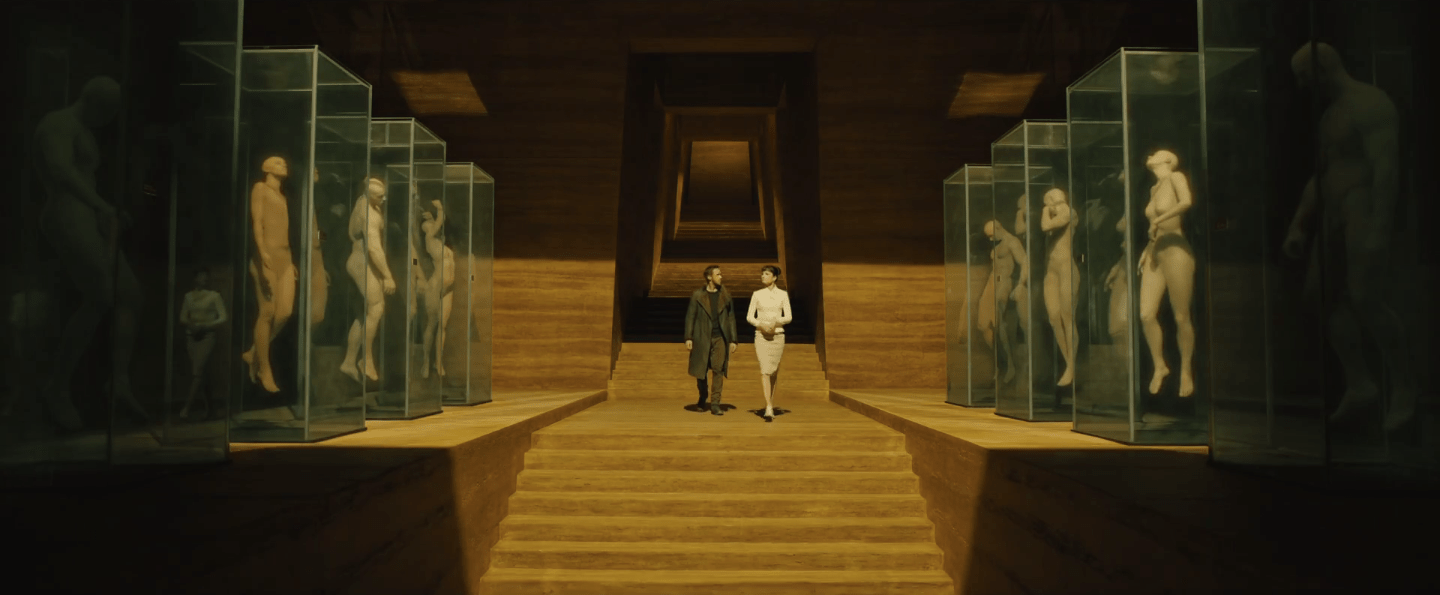

Because of this, the actual plot takes on a different tenor than the first, something closer to a spy thriller than the original detective yarn. The shallow callbacks come front-loaded: We get a new extreme eye close-up, a new future LA skyline, a new opulent replicant-maker, even a new zoom-and-enhance scene, all within the first twenty minutes. I find myself excusing that in hindsight, though – as the story develops and delves deeper into more contemporary SF allusion, we get a sense of uncovering subtler secrets, levels below what we thought we knew.

There are, no joke, three or four replicants in the background of this picture. Which ones? You don’t know! SECRETS!

Not all of those secrets are happy to learn. The story suffers more than a little when attempting to set up future movies in what we now have to call the franchise, Hans Zimmer’s score seems almost embarrassed of itself and should be, and anyone who tells you Jared Leto is good in the movie has been fooled by how clever everything around his performance is – he’s acting in the Prometheus version of this movie, not the Arrival one. There’s just so much to recommend, though, that takes up the lion’s share of the movie – Roger Deakins’ dreamlike cinematography that puts the visuals in the same weight class as the original, Harrison Ford showing he ‘s still got it with a Rick Deckard even more pickled in regret and booze than we last saw him.

Us sci-fi film fans have been spoiled, of late. In this year of more brilliant science-fiction movies than we really grasp, when uneven and competent crowd-pleasers like Life get tossed aside, it’s worth reflecting how high are standards are. More than that, though, it’s worth reflecting how handily Blade Runner 2049 exceeds those standards in every area that matters. Like all worthwhile SF, this is one that’ll have people talking.

Just to kick things off, notice how half the speaking cast is (fascinating) women, while in the original only half the replicants and none of the humans were women. A lot to unpack, there.