Thematic storytelling is cornerstone, foundational stuff. The elemental way into a story for me is strongly executed and adhered-to reliance on theme. Theme informs character. Theme reinforces story. It forms a firmament upon which all other elements of a story can thrive.

online pharmacy purchase priligy online best drugstore for you

Sometimes, theme is what makes a thing work. Subtext, tying disparate or seemingly superficial story and character elements together enriches the pieces of the whole, infusing the individually assembled appendages with an animating soul. Without it, all the craftsmanship and details of setting and plot can become pure window dressing, serving as nothing but decor.

But why am I talking about theme when you want to get to the clowny-kill-bite stuff? “Hey nerd, is it good?! Does Pennywise suck? Is it like the book? Is that scene in it?”1

I’m happy to report that Andy Muschietti’s feature adaptation of Stephen King’s novel is very good, if occasionally taxed by its own ambition. The young actors who portray our seven leads, the Losers’ Club, are almost uniformly excellent, giving fully realized performances that fairly shame every other actor in the film, save one.

Projecting myself into a future where It has permeated in the culture long enough to be weighed fairly against its staid television predecessor (and potentially against its own sequel), I feel confident in stating that this film is going to matter to a younger generation more than it does to the X-ennials it was aimed directly at. In fully crafting such a spiritually true adaptation, Muschietti has seemingly struck that perfect balance of wonderment, terror, empowerment, and utter powerlessness that comes from being a young teen at the mercy of the power structures around you that you simply cannot fathom, let alone partake. There is a beating heart at the center of It, and the completeness of place achieved here keeps the blood pumping, even when individual elements like character throughlines or effects fall behind a little here and there. Part of this is because this creative team have chosen to make their theme really matter, and the theme of fear is wonderfully woven into every aspect of the film’s construction and execution.

It is a treatise on the very nature of fear, from the unique perspective of each of its characters. It is consumed with the ways we experience fear, both physically and mentally, in our formative years. The things we see in a dark room at a young age aren’t ‘our eyes playing tricks’. They are happening. The very real breath of the monster behind us as we turn tail and run out of that room isn’t a conjuring. It’s happening. The deafening roar of void of the monster’s absence is a sound that has the weight and texture of the blood pumping in our veins, made more palpable by the fact that we know the beast is intruding into our world even as we understand it isn’t physically there. Muschietti plays with those sensory-aural inputs to delightfully creepy effect, tagging the recurring horrors of the film with their own unique signifiers and buttons, specific to the characters they are designed for. And while some of the elements of CGI and presentation don’t always gel neatly, and some of our characters are given short shrift (Mike, we barely knew ye), the overall strength of theme, setting, and character dynamics carry the film adroitly. And Pennywise’s own surreal unreality lends itself to an experience that, through reinforcing the singular vibrancy of the preadolescent lens, is greater than the sum of its parts. Not content to dwell on the more macabre and expected iconography of scary clownage, It is a buffet of youthful terror, and this film plays with the ways fear is woven into all other heightened, prepubescent emotions.

Ultimately, fear is the unwilling expectation that that which we cling to will be taken from us, or twisted beyond our understanding of it. King understood this, and used it to great effect to weave evolving fears into decades of his characters’ inner lives. Though I was initially dubious of the plan to isolate the childhood and adulthood aspects of the novel into separate films, doing so has lent a purity of focus to It, and a freedom to explore the theme of fear through our characters experiences, rather than their exposition. The members of the Losers’ Club each bring their own outsider perspective and traumatic baggage to bear in this story, and they do it as children would.

online pharmacy purchase propecia online best drugstore for you

While the film can struggle for balance amongst the seven leads, they all serve the greater thematic work that the movie is doing. Bill’s fear that he let his brother die defines his need to protect and avenge others, even as his guilt drives him towards a reckoning. Bev’s fear of her own maturation, exacerbated by the imperious attentions of her abusive father, inform her desire for agency and power. Finn Wolfhard’s hysterically funny portrayal of Richie hides his fear of loneliness behind a plate-steel armor of jokes and bits. Each character gets a varying thickness of skin to really live in in It, because Muschietti has found emotional truth with all of them to play with. Their fear unites them, but the love the characters display for each other on screen is what makes this film so special. The novel It isn’t really a straight up horror story. It is the story of seven people grappling with their own natures in the changing river of time, while being hunted by a supernatural crocodile. While the aperture closes tightly on one half of that experience in It, the story is not restricted, but rather freed. These kids are doing fantastic work, and their performances alone would be enough to dictate you see this in a theater.

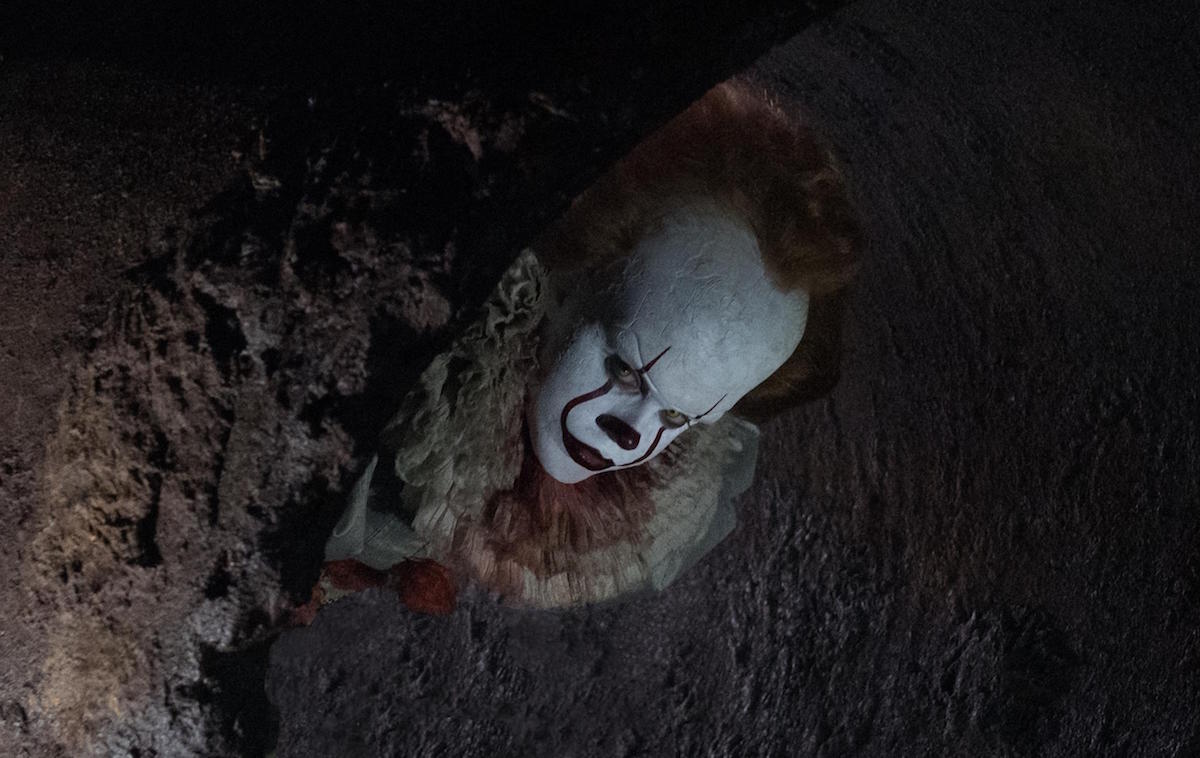

But hot damn, beyond the kids and the setting, you gotta show up for Bill Skarsgard’s Pennywise the Dancing Clown. Tim Curry’s performance is etched in stone as a classic of horror, and it would be foolish and boring to try to come anywhere close to it. Good thing this Pennywise is not interested. This Pennywise is every bit the crocodile I mentioned before. Skarsgard took an opportunity to play an embodiment of fear and chose to infuse it with a subtly masked iteration of that very thing. This Pennywise is less of a cartoonish, aggro prankster than Curry, though that aspect is utilized to a different effect. This Pennywise is alien. This is an ancient, unknowable extradimensional creature driven by greed. Terrified of starvation. Over (assumedly) millennia, Pennywise has developed guile, charm, and at least some genuine malicious humor. But these are trappings. At It’s root, this is a creature driven by primary needs and elemental fears, manipulating its food in the only way it knows how, by tapping into the deepest parts of us and shaking loose as much foundation as necessary to get us on the plate.

Skarsgard is unsettling enough at the basic layers, but there’s also an element of wrongness in his delivery of even cheerful barbs that reads more as necessary theater than pure malevolence. None of this is to say that It isn’t scary, though, as the unique spectres Pennywise conjures for each of the Losers are largely very effective. Some of the showier ones have especially stuck with me, like Egg Boy, The Painting Woman, the Leper, and the slideshow reveal. And it’s mostly amped up in sound design and editing, even when some of the CGI or pacing of a showpiece pulls you out of the moment.

But when It has let the facsimiles go, and we catch a glimpse of those teeth, that’s when the real fun begins.

A lot of films trot out the creatives during press tours to wax on about the deeper meanings in their latest work, with myriad soundbites of directors and actors assuring us that the newest job they’ve taken has ‘something to say’, on a deeper thematic level. Most of the time, this is faintly hollow salesmanship, already forgotten by the time the film has premiered and the grosses are counted. If you remember the release of Batman Begins, you remember being brained repeatedly by the factoid that the theme of the film was FEAR. Fair enough, as every character in the film has got one or two exposition pieces to inform you about their stance on that rust-hued emotion. But to what end? Can we pinpoint a moment in that film where the actual feeling of fear is conveyed to the audience as anything but an abstraction? Do we grapple with that emotion through our characters, or experience fear through them? If Pennywise the Dancing Clown were to manifest to a character in that or similar films, I assume he might appear as a book. About fear.

It is a horse of a different color. This film takes special delight in presenting fear as part of the broader spectrum of the human experience, and isolating it to the perspective of those who experience it in its most refined form. But through that specificity, It is able to paint on a larger canvas. Given the assuredness of Muschiatti’s brush this time out, I can’t wait to see the negative image promised in Part II.