In a film series chock full of moments, phrases, and images that have entrenched themselves into the pop culture lexicon for nearly half a century, the most instantly indelible aspect of Star Wars might be the first film’s opening crawl.

It’s an iconic blend of visual storytelling, emotionally stirring music, and old fashioned silent film-esque expository writing. And while it’s influences are many, there really isn’t anything quite like it. It transcends its roots in the sci-fi adventure serials of old and has yet to be replicated (outside of the Star Wars series itself) in a meaningful way. Without ever showing more than prose on an astral tinged setting, the audience is plucked from their seats and immersed into a world of action, adventure and excitement.

The Music

After being quietly lulled into a sense of calm by the words “A long time ago, in a galaxy far, far away” written in a visually appeasing blue hue, Williams immediately breaks the serenity with a blaring Bb chord from what sounds like the largest horn section of all time accompanied simply by the yellow emblazoned words “Star Wars”. It’s a simple, single chord combined with essentially just a title card, but it immediately sets the tone for the bombastic adventure that we’re about to go on.

This is followed by a Wagnerian theme that brings life to what is essentially a giant exposition dump in onscreen text. Lucas understood that, because we’re being swept into this weird world of space wizards and planet destroying floating orbs, the audience needs something familiar that can ground the film. Lucas did this in the film through Luke Skywalker, the young everyman farmboy who longs for something more as most everyone does in their youth. John Williams, probably the greatest film composer of all time, does this by using the classical stylings of film scores of the past as a template and turning the extravagance up to 11.

Williams’s score for the original 1977 film was influenced primarily by the works of Wagner, Tchaikovsky, and other classical composers1, but his main theme reaches to something that was more familiar to the public conscience. Kings Row, a 1942 film starring future US President Ronald Reagan, featured music by Erich Wolfgang Korngold that became the base influence of Williams’s opening theme. While not an overwhelmingly commercially successful film at the time, it was enough of a financial and critical hit to garner multiple Academy Award nominations, including one for Best Picture. And while Korngold’s music for Kings Row wasn’t necessarily something that would have been wormed into the brains of everyday moviegoers, his work on 1938’s The Adventure of Robin Hood is still the pinnacle of romanticized adventure film scoring.

While obviously not a like for like plagiarism, it would be dishonest to deny the clear influence and similarities between these two pieces of music. It’s an interesting, and clearly intentional, choice by Williams because it provides a base level of familiarity to the audience without the works being referenced being immediately in the public conscience. It’s this familiarity and grandeur that makes the sci-fi/fantasy verbiage of the opening crawl more palatable for everyone, from children to octogenarians.

The Script

The most challenging part of science fiction filmmaking is worldbuilding in a way that isn’t unwieldy and clunky. Star Wars is no exception, as Lucas needed to establish a civil war, the sides of the conflict, the stakes, the film’s superweapon — all while setting the stage for the film’s first scene. Lucas, whose love for sci-fi adventure serials like Buck Rogers and Flash Gordon was his original influence for Star Wars, looked to these serials for inspiration, both of which used titular crawls to spout exposition for each episodes’ adventure. Dan Perri, the title card’s designer, also brought Cecil B. DeMille’s Union Pacific to Lucas’s attention as it featured a similar crawl, and the duo decided to go ahead with the idea.

Note the similar capitalization method used in this FLASH GORDON crawl

The actual content of the crawl is one of the most impressive feats of expositional brevity I can think of. It quickly provides information in a way that is fully formed without being long-winded and tedious. It succinctly lays the archetypal foundation (“evil Galactic Empire”, “DEATH STAR”, “sinister agents”) as well as the immense gravity of the story being told (“ultimate weapon”, “destroy an entire planet”, “restore freedom to the galaxy”). We get the barest bones of the plot, but just enough that it provides the audience a reason to be invested in the peculiar gray triangle shooting at the tiny ship in the film’s opening scene. This conciseness is thanks in large part to legendary director Brian De Palma who helped edit and rewrite the text down in order to prevent the audience from becoming overwhelmed or uninvolved.

It is a period of civil war. Rebel spaceships, striking from a hidden base, have won their first victory against the evil Galactic Empire.

During the battle, Rebel spies managed to steal secret plans to the Empire’s ultimate weapon, the DEATH STAR, an armored space station with enough power to destroy an entire planet.

Pursued by the Empire’s sinister agents, Princess Leia races home aboard her starship, custodian of the stolen plans that can save her people and restore freedom to the galaxy….

It’s also interesting that, of all the memorable and downright legendary characters that Lucas would create in Star Wars, Princess Leia is the first to be mentioned. No mention of Luke, our POV character, or Darth Vader, the visual representation of the Empire’s cruelty and ruthlessness. Rather, Lucas harkens back to the simplicity of fairy tales by first familiarizing us to a princess in need of rescue. It’s a brilliant choice because it hints at the personal stakes of our future adventure without telegraphing exactly where the film is going.

The Visuals

A black starry backdrop representing the cold, vast nothingness of space is prompting breached by the yellow outlined title card. It’s a provoking illustration, one that elicits that Star Wars isn’t going to be a science fiction film that’s going to grapple with current social issues or deal with weighty thematics like, say, Star Trek or Planet of the Apes. Instead, it lets us know we’re going on an adventure, that space is full of vibrancy and life, and that the galaxy and universe is replete with breathtaking journeys around every corner. Combined with the magnificence of the film’s score, this simple visual moment tells us, without uttering a single word other than the film’s title, that Star Wars isn’t grounded, it is grandiose.

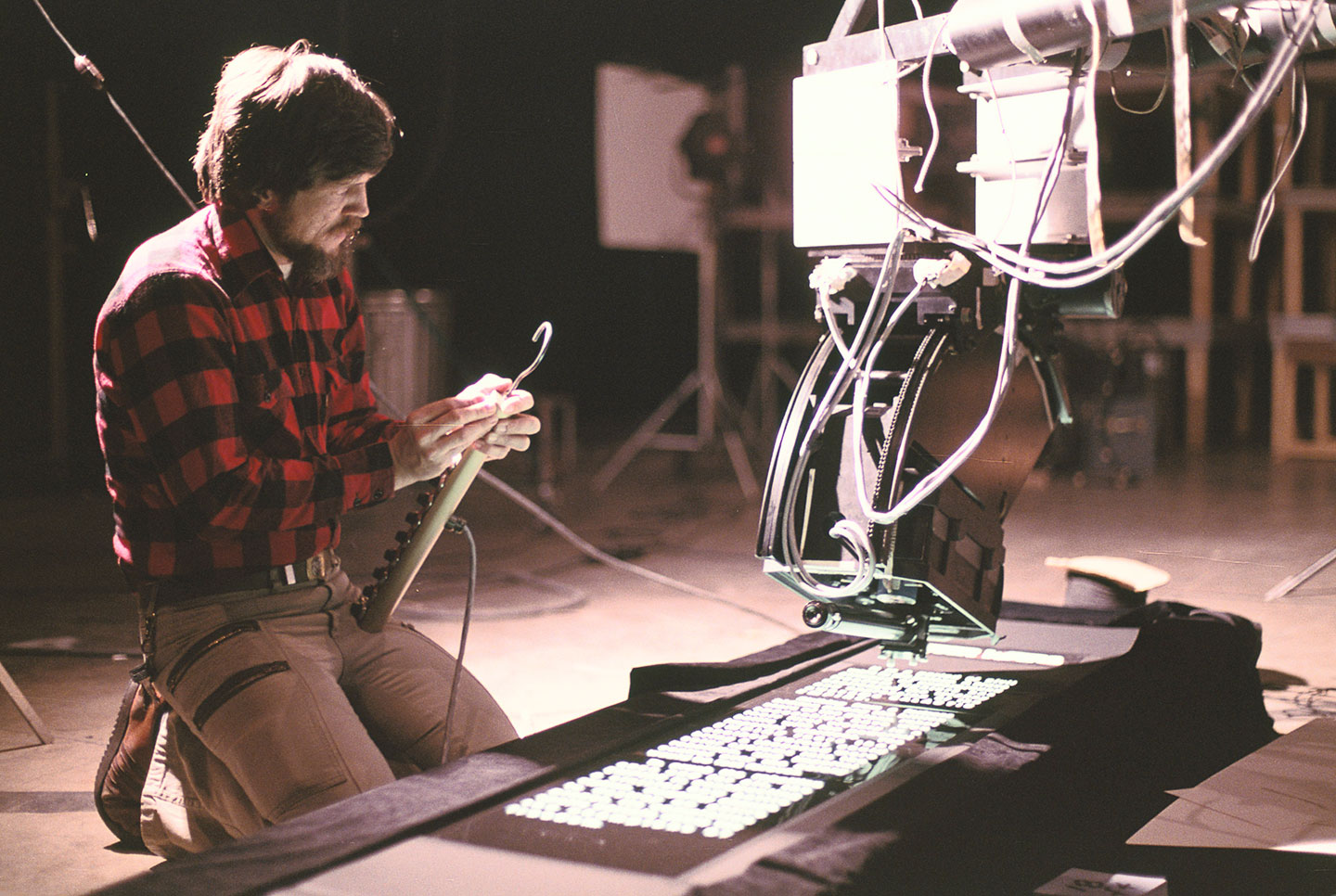

The fading title card gives way to the film’s crawl passages which move at an angle both upward on the screen and away from the audience, similar to the serials of Lucas’s youth. Unlike these serials, however, the backdrop remains a view into an empty cosmos. The audience is being pulled toward the screen, subconsciously being coaxed into joining this cinematic quest across the galaxy. To quote Up, it’s a the film sharing it’s yearning that “adventure is out there!” It’s both an introduction and an invitation to the world of George Lucas’s immense imagination.

Star Wars is, in many ways, a miraculous work of art—as our very own Brian Willis noted, it’s one of a kind storytelling that weaves myth, folklore, and an academic backbone. It’s a combination of a production filled with inventive and talented artists working together, both in front of and behind the camera, under a singular, visionary director. And it’s tough to imagine a full blown Star Wars film without the opening crawl. It’s iconography that’s just as important to the Star Wars series as Lightsabers, The Force, and the Skywalker name. In fact, the Rogue One immediately indicates its intention to not be your traditional Star Wars by teasing an opening crawl with the “A long time ago, in a galaxy far, far away” quote and rapidly cutting to the actual film. It’s an enduring cultural touchstone that is, in many ways, a perfect example of the nigh-impeccable and creative visual and non-visual storytelling of the original Star Wars film.

- As well as some composers of foreign films like Alessandro Cicognini’s score for The Bicycle Thieves