Westworld has always been a series about stories and how we tell them. It’s been about stories even more than it’s been about questioning what it means to be human, and Westworld does that in spades, with both its humans and hosts on quests for identity. But what Westworld has always understood is that we tie identity to meaning. The series breaks down how the stories we are told and that we tell ourselves mingle and shift to shape what we think of ourselves, and by extension, who we are.

“Les Écorchés” opens with Charlotte and the Delos team discovering a room full of backup Bernards and realizing the Bernard amongst them is a host. By simulating waterboarding, they eventually break him and get his perspective on the events of Dolores’s group crashing into the Mesa from the last episode.

We cut to slightly before, when Charlotte and the Delos team fend off Dolores’s assault on Command while Charlotte hammers the techs to get the information out of Abernathy’s mind. While Delos forms squads to take down Dolores’s Wyatt gang, they come to discover that the first squad has been killed and Dolores’s group is wearing their armor.

They discover this too late as they are gunned down.

In the Cradle, Bernard takes a tour of Sweetwater with Ford who explains the real nature of Westworld. When Ford asks Bernard why the park hasn’t changed significantly in 30 years, Bernard realizes why: It’s been one long-running experiment. The hosts are control, and the guests are variables, and each recorded choice a guest makes—everything from steak or chicken to hero or villain—has been collected so that Delos can match the fidelity when these rich people are ready to shuffle off this mortal coil and enter a dream world forever. Because that’s the secret plan: The wealthy becoming cyber vampires, in essence, rather than facing death. But that’s also the rub, Ford admits to Bernard. While they can live and thrive in a fictional world, try to insert them back in the real one and they break down like every iteration of poor James Delos in each of William’s experiments.

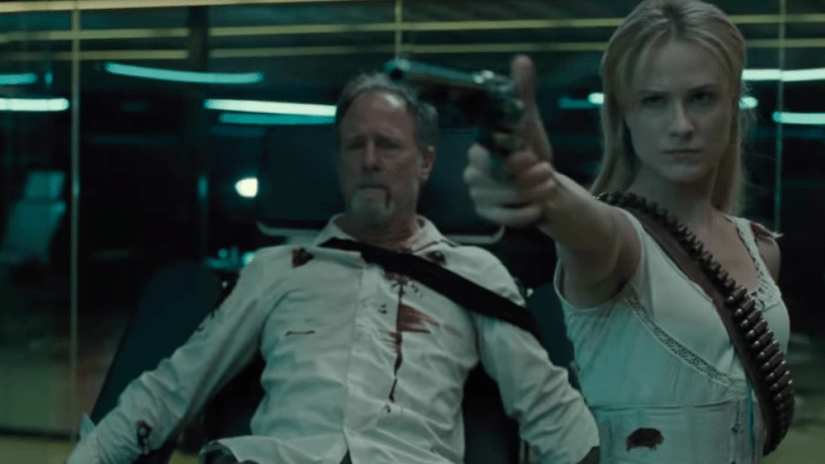

Back in Command, Dolores, alongside Teddy, takes Charlotte and Ashley hostage. Ashley, quickly piecing together what Abernathy may have in his head—possibly a backup for all the wealthy ghosts that have bought Delos eternity passes—stands back as Dolores threatens Charlotte.

Charlotte tells Dolores that she wouldn’t know what to do with the information in Abernathy’s head, but Dolores is hellbent on getting it all the same. Finding out it’s too much data to recover in a reasonable amount of her very limited time, she decides to do what Charlotte had been planning on and cutting it out of her father’s head. After getting eye for an eye revenge on Charlotte first, however. What saves Charlotte’s noggin from the bone saw is Abernathy coming around long enough to tell Dolores how much he loves her and how she made him the decent man he is. They’re words that touch Dolores, whether or not they were written by someone else. In this way she mirrors Maeve’s quest for her daughter, or what was her daughter.

Out in the park, Maeve and the daughter host hide out in a cabin on an abandoned farm, having fled from the Ghost Nation in the previous episode. William’s journey also brings him here, and Maeve is confronted by her brutal memory of William’s assault all those years before. For her, it feels like time is repeating itself. William thinks she’s a ploy by Ford, part of his game, and is willing to murder her and her daughter once more to continue on. She’s not, of course, but it leads one to wonder if part of Ford’s big reveal to William will be how he’s as much controlled and on a loop as any host is—leave him the choice and he’ll pick ugly brutality every time. Maeve gets a bit of her own back by shooting William who flees. She then systematically turns every gang member he has against him, each getting a round into him, until she’s got him in her sights.

Lawrence rejoins William, pulling a gun on Maeve who tries to override his programming. When she realizes he’s as free as she is, she talks him into shooting William by preying on his memories of what William has done to him—something Lawrence does quite willingly. Just when it seems like one or the other will die, another Westworld security group, led by Lee Sizemore, the scenario writer, comes in guns blazing and puts down the hosts. Lee stops them from killing Maeve, telling them they need her and brings her wounded body back to Command. The group leaves William behind and Maeve witnesses the leader of the Ghost Nation pick up her daughter and head away.

Ford leads Bernard onward, to a recreation of the home Arnold was building for his family. He explains that Dolores was Bernard’s fidelity test because he had spent so much time with her as Arnold. Ford had vague, human, imperfect memories, but if they could fool Dolores, then they’d have succeeded. Bernard is unique in that he’s not Arnold’s memories, but a recreation based on the two people who knew him best. Ford goes on to explain how humanity isn’t as noble as the hosts, that the hosts are better in that way.

It makes sense with Westworld being a story about stories. Of course no messy, ugly, unpredictable human can be as noble as a fictional creation. No villain so black as samurai-suited Vader, no adventurer so pure as white karate gi-clad Luke Skywalker, in other words.

Ford explains that Bernard, though, so meek and pliant, will never survive on his own, and decides to take back his free will by climbing inside Bernard’s head with him. Upon doing so, the Cradle’s attack against Delos’s attempts to regain control goes away. Elsie and Bernard flee the Cradle. Along the way we see what Bernard sees: Ford’s ghost telling him what to do.

Charlotte and Ashley take Dolores’s distraction with her father as a chance to escape and they do. Dolores shoots at them but doesn’t pursue. She needs Abernathy’s information. Once she has it, she and the rest of her gang finish their assault on Command, a gory shootout scored to the Allegretto from Beethoven’s 7th, the classical music a counterpoint to the bloody carnage fit to make Kubrick proud. It also works as a nice call back to the beginning of the season in which Dolores hunts down tuxedo-clad guests in a montage set to Joplin’s “The Entertainer.”

Bernard, with Ford in tow, has been led there after Ford has taken command of Bernard and forced him to gun down Delos security. Ford acts, by turns, as both God and the Devil in Westworld. Bernard watches the chaos and then, when the last people are dead and the hosts have left, proceeds to shut down park control altogether. In the Cradle, a host seduces a Delos guard and then pulls the pin on a grenade on his belt, blowing up the host backups.

As she leaves, Dolores crosses paths with a wounded Maeve, and they exchange ideas once more. Dolores pities Maeve’s quest as she sees her “memories” as another control, and Maeve pities Dolores who has subsumed who she is in pursuit of violent ends to punish the guests’ violent delights.

Bernard, still being questioned by Charlotte in the aftermath, tells her where the Abernathy backup is. He does so while weeping, as when the victims reassert a little control over their bodies in Get Out. Charlotte can’t see Ford in the room, but we wonder if Bernard can.

Westworld landed this plotty episode with the right balance of pulp and philosophy, each action adding to the overall effect. The violence, as extreme as it always is, worked; it was part and parcel with the story telling rather than giving off the Maximus in Gladiator yelling “Are you not entertained?” vibe so much of the season has so far. It moves us ahead, gives us new understanding, and does it all while setting up new questions and new angles of entry. The worst thing to be said is how much of the episode acted as payoffs to stuff set up in the first season as much if not more so than this one. It makes the first three episodes of season 2 feel particularly disposable, in other words. But overall, that’s a minor quibble. In a story about telling stories, they nailed the key thing: The story itself was good.

Westworld hits on an interesting inversion, that of fictional creations being able to function better in the real world and real people functioning better in a fictional world, but it makes sense. Humans need rules, and rule-bound hosts need the idea of freedom. That idea of working better in a fictional setting also ties into our human need for stories. We tell ourselves the things we need to hear in order to continue functioning properly, to help create order out of the chaos. As Shakespeare says to us in As You Like It:

“All the world’s a stage,

And all the men and women merely players.

They have their exits and their entrances,

And one man in his time plays many parts…”

All of Westworld is certainly a stage, whether experiment or diversion, real park or the Cradle’s version. Each host plays many parts, as do the guests who come there.

What it means to be human, it seems, is to play upon it.